Introduction

Southwark holds literary connections to three of England’s most celebrated writers: Geoffrey Chaucer, William Shakespeare, and Charles Dickens. Of these, Dickens captured the grim realities of 19th-century life with a vividness that still resonates today — especially when writing about debtors’ prisons such as Marshalsea.

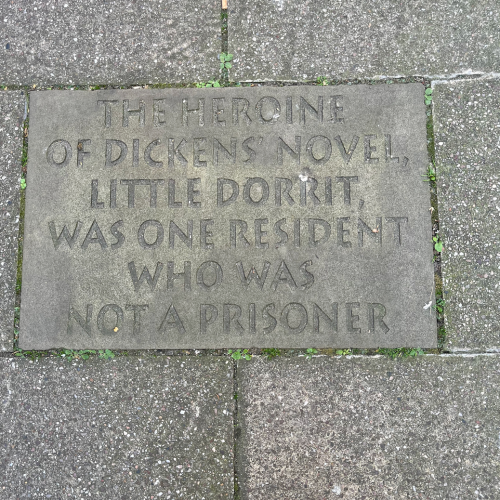

The Marshalsea features prominently in The Pickwick Papers, David Copperfield, and most notably, Little Dorrit, where the titular character, Amy Dorrit, is born within its oppressive walls. But why did Dickens return so often to the subject of debt and incarceration?

A Childhood Shaped by Debt

Until the Bankruptcy Act of 1869 brought an end to debt imprisonment, Southwark was home to a debtors’ prison almost continuously from 1300 onwards. The original Marshalsea was rebuilt in 1811 but retained its legacy of confinement and despair.

In 1824, when Charles Dickens was just 12 years old, his father John Dickens was imprisoned in the Marshalsea for a debt of £40 and 10 shillings owed to a baker. Rather than follow his family into the prison, as many children did when families couldn’t afford separate lodgings, young Charles was sent to work.

He took a job at Warren’s Blacking Factory, near today’s Charing Cross, where he spent ten-hour days pasting labels on bottles of boot polish for six shillings a week. He walked five miles from his lodgings in Camden to get there, and after work, he crossed Blackfriars Bridge to visit his family at the Marshalsea, often bringing them food.

This chapter of his life left an indelible mark. Dickens was so deeply ashamed that he told no one outside of his immediate family — not even his own children. Only his wife, Catherine, and his friend and biographer John Forster knew the truth. It was Forster’s posthumous biography that revealed Dickens’ hidden past and illuminated the personal anguish behind his writing.

A Prison Like No Other

The Marshalsea was one of five prisons in Southwark.

South of the river, beyond the jurisdiction of the City of London, the area gained a reputation for lawlessness. It was filled with taverns, brothels, gambling dens, bear baiting pits, and theatres — an appealing playground for visitors, but a place of hardship for many residents.

The name “Marshalsea” derived from a “marshalcy,” or office of law, not the maritime history of Southwark. Originally, the prison held men accused of crimes at sea, such as smuggling and piracy. Over time, it evolved into a prison for debtors, though the conditions remained brutal.

Until the late 18th century, prisons functioned more like holding centres where inmates awaited their fate, be it repayment, execution, or transportation to penal colonies. The prison system was run for profit. Inmates were expected to pay for their food, bedding, and even the fines set by their jailers. Without outside help, many debtors simply starved.

This bleak reality is embodied in the character of Mr Dorrit, Amy’s father in Little Dorrit. His debts are so convoluted that no one can understand them, let alone resolve them. He becomes a metaphor for a system that traps the poor in confusion and despair.

Dickens' Southwark, Then and Now

Charles Dickens’ time in Southwark was very different to the world Chaucer described in Ale, Bread and Pilgrimage: Chaucer’s Southwark and the Appetite for Life. After visiting his family, young Dickens would walk back to his Camden lodgings at night, returning each evening after the Marshalsea gates closed at 10pm.

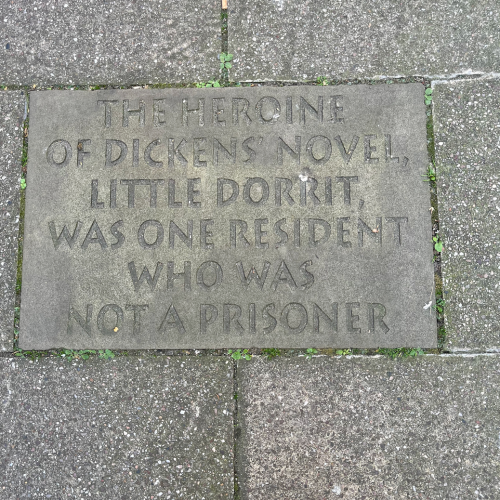

Though the Marshalsea closed in 1842, a portion of its southern wall still stands. The rest lives on in Dickens’ words, which haunted Victorian readers and helped usher in much-needed social reform. He wrote of the “crowding ghosts of many miserable years” that lingered within those walls — a powerful image of suffering hidden in plain sight.

Today, it’s easy to miss the small plaque tucked away off Borough High Street that marks the remains of the Marshalsea. Most passers-by are likely heading to the nearby pubs and market stalls, unaware of the ghostly past surrounding them. For those curious, we recommend our guide to Things to Do in Borough Market to help you explore more of the area’s character and history.

Want to Know More? Plan a Visit

Book onto our tour private Southwark: Pilgrims, Playwrights and Prisoners. This tour explores into stories no guidebook can offer, explores tucked-away passages, and might even end with a local pub recommendation or two. This walking tour is available as a guided walk or private tour, both with a personal touch.

📚Read more: Shakespeare’s Globe Theatre

🎧Listen to related podcasts:

Episode 50: History of Shoreditch