Tobias Smollett's London Life: From Struggling Surgeon to Literary Satirist

Tobias Smollett’s London life was a study in contrasts: a young Scottish surgeon struggling to establish a medical practice on prestigious Downing Street, and later a celebrated novelist hosting glittering salons in Chelsea. His experiences in the capital shaped his sharp eye for hypocrisy, social pretension, and human folly—qualities that made him one of the most distinctive satirists of the Georgian age.

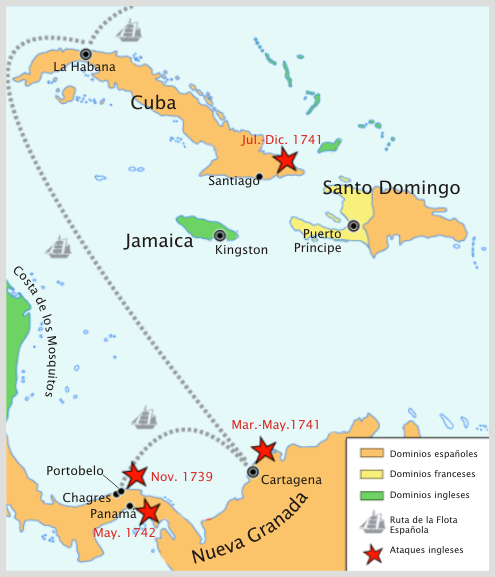

From his service as a naval surgeon in the Caribbean to his editorship of The Critical Review, Smollett lived through both hardship and literary triumph. London provided him with patients, rivals, friends, and enemies, as well as an endless supply of material for his novels. Whether mocking bureaucrats, lampooning doctors, or capturing the speech of London’s streets, Smollett transformed daily struggles into biting satire that influenced writers from Charles Dickens to later Victorian novelists.

Smollett Arrives in London

Tobias Smollett (1721–1771) arrived in London from Scotland in the early 1740s with a medical degree, boundless ambition, and a manuscript for a tragedy in hand. Like many Scots of his generation, he saw the capital as both an opportunity and a trial—a place where one could rise quickly, or fail just as fast. Smollett’s first attempts to establish himself were through medicine, but literature would soon dominate his life.

After serving as a naval surgeon during the War of Jenkins’ Ear and spending time in the Caribbean, he returned to London hoping to practise as a physician. He set up in prestigious Downing Street, but his career as a surgeon foundered. The fashionable patients he sought never materialised, leaving him frustrated and financially insecure.

Downing Street Struggles

Smollett’s time on Downing Street revealed both the promise and pitfalls of Georgian London. While the location placed him close to the corridors of political and social power, it also highlighted the intense competition among physicians, surgeons, and apothecaries. Smollett was skilled, but lacked the connections needed to secure wealthy patients.

The experience sharpened his sense of exclusion and provided rich material for his satire. Characters in his later novels often include hapless or pompous doctors, a clear echo of his own struggles in the medical profession. What he failed to achieve in Downing Street through medicine, he would eventually achieve through the written word.

Rise as a Novelist and Satirist

In 1748 Smollett published The Adventures of Roderick Random, a biting picaresque novel that drew heavily on his naval and medical experiences. It was an immediate success, propelling him into the literary circles of London. The novel’s vivid episodes, scathing humour, and sharply observed characters resonated with readers and placed him alongside Henry Fielding as a major voice of the age.

Other works followed: Peregrine Pickle (1751), The Adventures of Ferdinand Count Fathom (1753), and later The Adventures of Sir Launcelot Greaves (1760). His final masterpiece, The Expedition of Humphry Clinker (1771), offered a panoramic view of Georgian society, often drawing directly from his London experiences.

Chelsea Salons and Literary Feuds

By the 1750s Smollett had moved to Chelsea, a riverside district that was emerging as a cultural and intellectual hub. Here he hosted literary gatherings that attracted writers, thinkers, and actors. His reputation as both novelist and critic made him a central figure in London’s literary world.

Smollett also became editor of The Critical Review, one of the city’s most influential journals. His sharp pen made him powerful and controversial. He engaged in fierce disputes with fellow writers, including Laurence Sterne and Henry Fielding, and was once briefly imprisoned for libel. Yet these battles only enhanced his reputation as a fearless satirist unafraid to target hypocrisy in politics, medicine, and society.

Georgian London as Inspiration

Smollett’s novels teem with the sounds and sights of 18th-century London. From taverns and theatres to doctors’ surgeries and debtor’s prisons, his stories reflect the social fabric of the capital with unflinching detail. He was fascinated by language, capturing the slang, dialects, and cadences of Londoners in a way few of his contemporaries attempted.

The city provided him with both triumphs and grievances. He complained often of its damp climate and the toll it took on his health, yet London gave him the audience, networks, and rivalries that defined his career. Without its teeming streets and turbulent society, his satire would have lacked its cutting edge.

Smollett’s Enduring Legacy

Tobias Smollett died in 1771, but his London years left a deep imprint on English literature. His novels influenced Charles Dickens, who admired Smollett’s ability to capture character and dialogue. The humour, sharp observation, and social critique in Humphry Clinker in particular prefigure many Victorian literary themes.

Though his medical career failed, Smollett’s frustrations as a Downing Street surgeon enriched his literary voice, turning personal disappointment into satire that still resonates today. His Chelsea years showed how an ambitious outsider could become central to London’s cultural life, using wit, resilience, and imagination to make his mark.

Tobias Smollett’s London life was a journey from failed physician to one of the most original satirists of the Georgian age. His struggles on Downing Street, his triumphs in Chelsea, and his ability to transform frustration into biting social commentary all underscore how deeply London shaped his career.

🎧 Listen to London History Podcast Episode 139: Downing Street – A Microcosm of London and learn more about the former residents of Downing Street.

📖Recommended Reading:

- Primary Works – Smollett’s Novels

- The Adventures of Roderick Random (1748)

- The Expedition of Humphry Clinker (1771)

- The Adventures of Peregrine Pickle (1751)

- Tobias Smollett by Jeremy Lewis (Vintage, 2004)

- Tobias Smollett, MD: His Medical Life and Experiences (Hekint Journal, 2017)