Join host Hazel Baker and Cat Bateman from Little Folk Nursery Rhymes as they discuss London Nursery Rhymes.

Nursery rhymes include:

- Mary, Mary, Quite Contrary

- Ringa, Ringa Roses

- Three Blind Mice

- London Bridge is Falling Down

- Pop Goes the Weasel

London Guided Walks » Episode 65: London Nursery Rhymes

Join host Hazel Baker and Cat Bateman from Little Folk Nursery Rhymes as they discuss London Nursery Rhymes.

Nursery rhymes include:

Hazel Baker: Hello and welcome to London Guided Walks London History podcast. In the coming episodes, we will be sharing our love and passion for London, its people, places and history in an espresso shot with a splash of personality. For those of you who don’t know me, I am Hazel Baker, founder of London Guided Walks, providing guided walks and private tours to Londoners and visitors alike.

Hazel Baker: Hello and welcome to London Guided Walks London History podcast. In the coming episodes, we will be sharing our love and passion for London, its people, places and history in an espresso shot with a splash of personality. For those of you who don’t know me, I am Hazel Baker, founder of London Guided Walks, providing guided walks and private tours to Londoners and visitors alike.

We’re going to be discussing some of London’s nursery rhymes. And who better to do that with than someone who sings them for a living. Today’s guest is Cat Bateman, Hello Cat.

I am Cat Bateman, live in Sydenham with my husband and two boys (14 & 12) and for over 9 years have been running my small business ‘little folk nursery rhymes’ stringing with my guitar to must be now in the 1000s of little ones, the much loved old traditional songs and some newer classics! I am completely passionate about music and singing for everyone and feel bloody lucky to have turned my passion into a business!

Cat Bateman: Hello, Hazel.

Hazel Baker: What are nursery rhymes for you, then?

Cat Bateman: I’m sure everybody listening does know what a nursery rhyme is, but I think the basic definition I think is that it’s a pleasing rhythmic pattern with simple, repetitive phrases that babies and young children find easy to remember and repeat. And I think that’s their kind of their basic function.

Hazel Baker: And where does the term nursery rhyme come from?

Cat Bateman: I was like really intrigued to look back in history and to see, you know, where they started, how they started. So I’m really grateful to you because this has been something on my list to do for ages. I’ve done lots of reading now, Hazel, thanks to you. And then it seems to have come from, there was a little bit called Rhymes for the Nursery in 1806 and it was published in London and it was published in Grace Church street, which is all part of that old historical city of London.

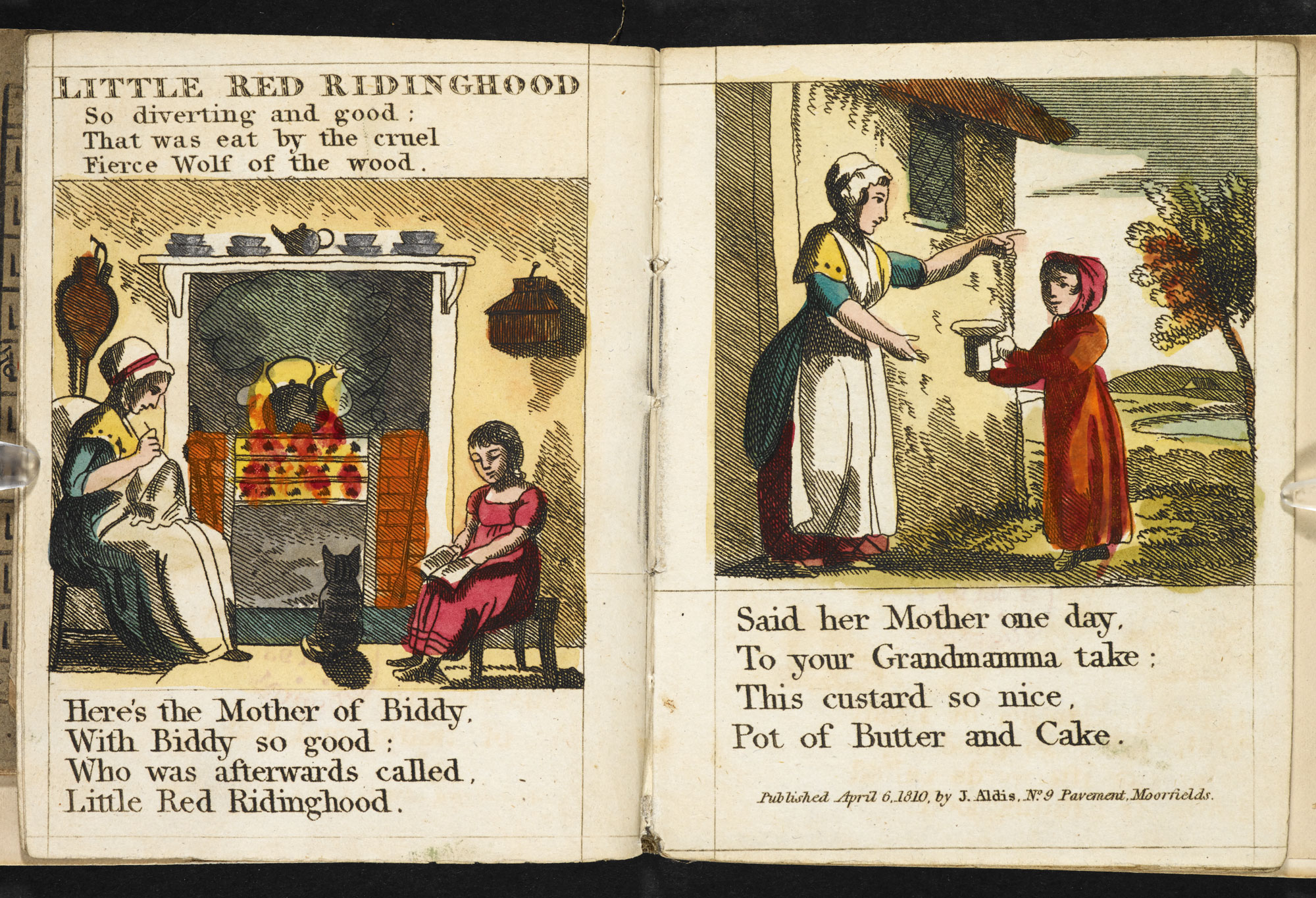

So I love the fact that there’s this like little centre that was considered to be where these things were starting to be printed and published. Like, I just love that, that there was a place you could go to collect these, they were called Chapbooks, I believe. And so for those of you that have never heard of Chapbooks, I’d not heard of it until like last week, they were these lightly gorgeous little pamphlet. So they weren’t hard books or anything. They were like a little pamphlet. They had up to like 24 pages in them. And they were just like collections of like little nursery rhymes, lullabies, little stories.

And in this one, so rhymes for the nursery, what I think is amazing is that on the spine of this one, and it was in guilt, which I think is really. Like, I can’t believe that it was in guilt those in those days, but it was, because maybe the title was too long, they just abbreviated it to nursery rhymes on the edge. And I think from that time on, they were called nursery rhymes. So I love that. That’s really fascinating to me that just out of necessity, they came up like that.

So that was the term nursery rhyme set. And I think why they came about, I think originally, although you think that nursery rhymes are just for children, don’t you? I mean, that’s just like the general consensus, they’re for children and stuff like that. But when you look further into it, as lots of people do, I think we can fairly safely say that the majority of nursery rhymes weren’t composed for children at all. It came from people trying to be underhand about how they fought against the sort of statutes of the time and things like that. So that was fascinating. I do feel that there’s a caveat to say that the accepted history is that nursery rhymes is often based on pure conjecture and it’s, you know, you just don’t know.

There’s not so many facts to back these things up, you know? What I love about nursery rhymes and I think we’re allowed to sort of stretch the sort of truth and things a little bit with it, because it’s a bit like, I did classics at university and a lot of the texts were started by the oral tradition and nursery rhymes are just really based in that.

And especially in times when, you know, London was full of sort of the majority were illiterate, so they would see these Chapbooks and they would love them because they had like really crude wood printed drawings in them. So they really loved them because they could look at the illustrations. But nicer ones needed to be sort of short and snappy because people couldn’t read so they could remember them and passed, you know, the whole audition obviously is passing these songs on from generation to generation, to, you know, all around the country and things. So I just love that. That’s how they started.

So I thought we’d get into the list. I’m just going to look at my list here. Oh, and one thing actually, Hazel, one thing that people, I think they just think nursery rhymes are just a bit like, you know, why would you bother with nursery rhymes? What are they? Why are they important? And I just think that, now I’ve done them for so long, I can see what they mean to little ones. And I see them as bite size learning opportunities. Repetition is key. Which is really good for me because it means I don’t have to constantly learn new things all the time. And I feel so honoured to sort of keep them going, you know?

So anyway, let’s get down to it. History shows us that some lullabies and nursery rhymes are anything but soothing. Because you do think that they’re just going to be really done so many lovely. The first one that really freaked me out was, and I think this is known by quite a lot of people actually, and I’d heard of it, but I hadn’t looked deeply into it.

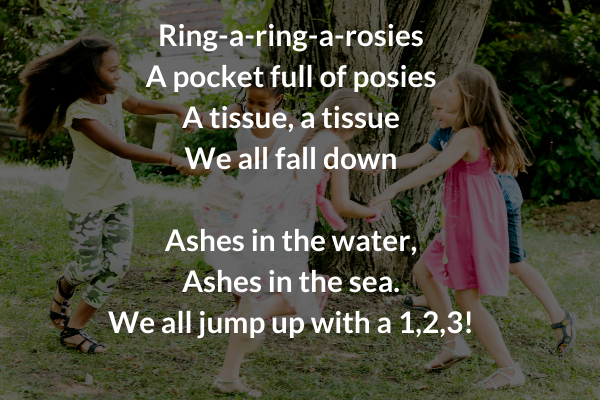

Ring a Ring o’ Roses

So I think this is a really timely one to discuss because of the pandemic that we’ve been going through.

And as the words go Ring a Ring o’ Roses a pocket full of posies. I’ve read some sort of reviews that say, they think this is linked to the black death in 1347. But I actually think I think I agree with the others that say it’s actually the great plague of London in 1665. So the bubonic plague. Because, I mean, it sounds disgusting, doesn’t it? It sounds like such a sweet little rhyme. Apparently the rashes that were experienced with the bubonic plague, they looked like rings and they were quite a rosy colour. And then people stuffed posies into their pockets so they couldn’t smell the dead bodies lying around and piling up.

Hazel Baker: I also thought that the smell, the miasma, if it smelled bad, then it would do them injury. They would get the disease through the smell, the air – That’s why you needed a posie.

Cat Bateman: Then there’s a bit where it says an awful down. And it’s basically because it wiped out 60% of London’s population. That one kind of freaked me out because you’ve got these beautiful little rhymes and lovely melodies, but actually it was about something quite dark and quite sinister. Yeah. That’s, that’s a nice one to start with. So that’s Ring a Ring o’ Roses.

What they tended to do as well with nursery rhymes was that they would use like a traditional well-named song so that people would know of the time and they would use that. And then either write some words to it or take someone else’s poetry. So Twinkle Twinkle is exactly this example. And I was fascinated to learn this cause I never knew this. I kind of assumed that they were, you know, there was a nursery rhyme singer songwriter just like pouring these things out. So Twinkle Twinkle, it actually combines the melody of an 18th century French tune, which was called Ah! vous dirai-je, maman, which is oh shall I tell you. And it’s mixed with a 19th century English poem by a poet called Jane Taylor, which was entitled The Star. And so that became sort of forced together somehow. No one actually knows how they were brought together, but they were. That has existed, like that’s still one of the most favourite ones that little kids love now.

And I just love that. And I do three of the verses cause there were five verses, but I do three of them. And I still love seeing how excited people are when there’s more than the first verse. So that’s beautiful. And I just love that, that it was a mixture of someone’s writing, a tune that everyone loved, and it just kind of came into the world like that.

There’s a really, are you ready for this one? Hold on, hold on to your hat, Hazel. This one, this one is quite freaky. So Mary Mary quite contrary. Okay. Beautiful melody. And it’s so sweet and kids love singing along to this one. And I just always thought that this was a really sweet little rhyme, but actually it’s a reference to Queen Mary I. So the historians seem to think that it was written to heckle her time on the throne because she was seemingly quite an evil Monarch. Contrary was a term that was often used to describe her nature of leadership at the time. And then if you look deep into the words where it says, how does your garden grow? Apparently that bit was mocking her inability to produce life children. Like, I mean, how mean is that? And then she was widely known for murdering, I think reports vary, but something like over 280 people, because she was a fierce believer in Catholicism and her reign as queen was 1553 to 1558. And it was marked by the execution of hundreds of Protestants.

Hazel Baker: That’s right including Smithfield.

Cat Bateman: Yes. Yeah.

Hazel Baker: And just out the city of London. And there’s a, there’s a plaque with the names on.

Cat Bateman: Is there?

Hazel Baker: Yeah. Yeah.

Cat Bateman: Hazel, you’re going to have to take me on a nursery rhyme tour. Let’s do a mastermind tour. That’d be amazing. Also the other words like silver bells and Cockle shells, they’re such beautiful trinket ideas, but actually they were a reference to her torture devices apparently. And then where it sings pretty maids all in a row. It’s either like, and again, you read all these different sources and they’re not totally agreeing with each other, but it seems to be either a reference to numerous miscarriages or dead bodies that she accumulated over her reign. Or the maids is a slang for a beheading instrument called the maiden. And that came into common use before the guillotine, apparently. I’d never heard of that, the maiden.

Hazel Baker: Well, she burned her victims.

Cat Bateman: Did she?

Hazel Baker: Yes. That’s what was the biggest insult. Was that you have the punishing position in Europe, which was headed up by her husband King Philip of Spain, and were worried that that was going to come to England. She executed the protestant priests, but she put them to death by fire on these stakes. Whereas that was a death reserved for women. These men, a woman’s death. How insulting is that?

Cat Bateman: Completely outrageous. Like a bit of a oneness Mary I.

Hazel Baker: It doesn’t do her any favours. I don’t think with this one, but when you see her, when she signed some charters, you see the picture of her. And the little iconography at the front and there’s her and her husband and the crown that which should be on her head is actually hovering in between them both because we haven’t yet successfully had a queen rule in our own right. Because don’t forget, Elizabeth is after her, right? So she’s actually pioneering for Elizabeth, made it a lot easier for Elizabeth. You know, we don’t think about those things anyway.

Cat Bateman: I mean, there was another one linked to her. See, she’s pretty hardcore, I reckon. We might love her today, but Three Blind Mice? So apparently the farmer’s wife is purported to be queen Mary. And then the three blind mice with a nobleman who were convicted of plotting against her and agreeing with what you’re saying, she had them burned alive at the stake. So the three blind mice were supposed to be the three Protestants who were Hugh Latimer, Nicholas Radley, and the Archbishop of Canterbury Thomas Cranmer. And they were all conspiring against to sort of overthrow her. She found out. She burned them at the stake for heresy. And then critics suggests that the blindness in the title of the mice refers to their religious beliefs. In other words, they were blind because they didn’t follow her religion. Yeah. How mad is that?

Hazel Baker: I haven’t heard of that one, that’s revolutionary.

Cat Bateman: It’s fantastic., Isn’t it? And then there’s other ones I found like Ding Dong Bell. This seems to be able to be dated back to the 16th century because references have been found in Shakespeare’s plays. And what I absolutely love about this, I got all giddy about this one because I don’t actually know that nursery rhyme that well, but obviously I’ve heard it over my lifetime. I love the fact that possibly, so in my head, I was thinking, oh, my God, so he’s written those words in plays. So Ding Dong Bell, specifically that phrase whilst he was living in London. So he was in Bishopsgate, wasn’t he? And then the clink. So not far from the amazing globe site now. And then apparently silver streets and pools and Blackfriars.

Hazel Baker: That’s right on a gate there.

Cat Bateman: Yeah. So I thought, oh my God, maybe he was in the city and he bought Chapbooks with the nursery rhymes in them. And so Ding Dong Bell and then put it in a play. And so that made me feel very happy. I just love the idea of thinking about him, wandering around the streets and looking at other literature and putting it in his work.

Hazel Baker: Yeah, he reads what other people were writing and-

Cat Bateman: So in my head, Shakespeare’s got a little chapbook and I’m really pleased about that.

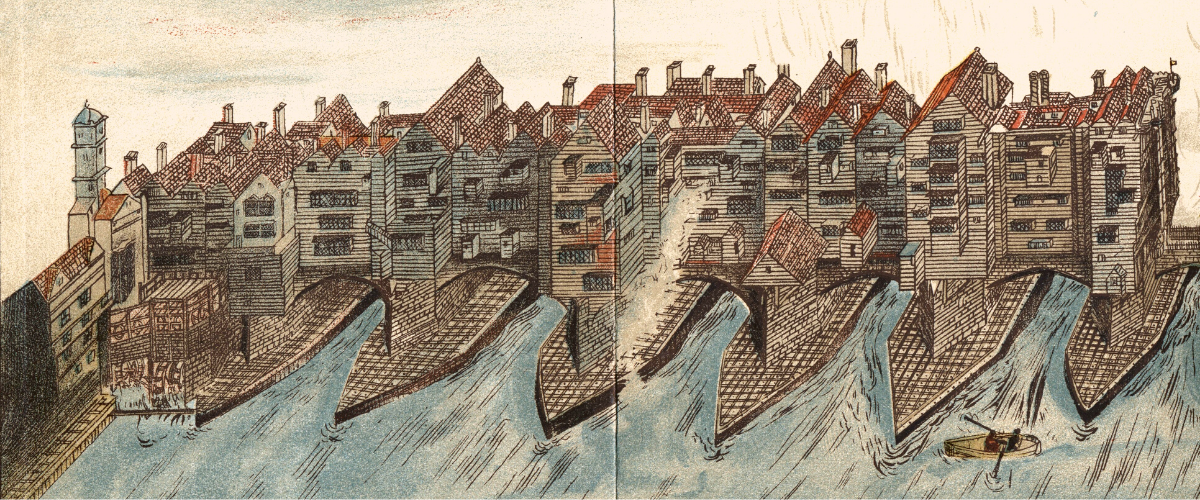

Clearly the main one is London Bridge is Falling Down. That’s a very good one. And you know, kids love doing that in the round and I’ve sung the words, but I’ve never thought about them. I literally, you just sing the ditty, the words come out and you do the falling down. Well, I found it difficult, Hazel, was to find a definitive answer. But I love all the different ideas. I think it’s just great to natter about them and to see what you feel might be true. And so one of the ideas was that the Vikings attached the bridge in 1009

That’s right. Yeah.

That was one thing that I have never known. And, you know, obviously there are lots of people that say that never happened, but there are some people that believe that. The second one, which I find really spooky and I hope it’s not true. Some people say that the bridges foundations were made of human children remains. I mean how awful is that? And I never heard that before. And apparently the only way to keep the bridge up and safe in all these times was to sacrifice another child.

Hazel Baker: Well, of course.

Cat Bateman: I mean, doesn’t it make sense? So I really, really hope that’s not true. There’s absolutely no proof that that is true. So I’m choosing to believe that that definitely isn’t true.

The only thing that I can find that seems to be true about it, is that we know when it’s things, my fair lady, she was supposed to be Eleanor of Provence who apparently owned the bridge between 1269 and 1281. So yeah, I think that bit’s true.

Hazel Baker: Yes. She was supposed to collect the taxes and use it for maintenance, but

Cat Bateman: So she just kept it.

Hazel Baker: Yes.

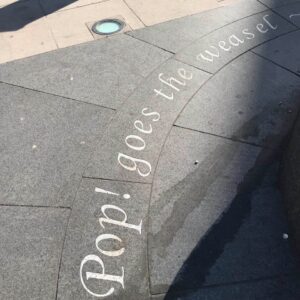

Cat Bateman: I mean, why not? I mean, why not? I mean, why not? Now I’ve got some, oh yeah. So this is another one. So Half a Pound of Tupenny Rice. This one, I really love this one. So this apparently was really popular in musical songs. So it was heard all through the streets of London in Victorian times in the theatres. The origins of the lyrics seem to be split. So one theory is that it has its origins in the sort of same grimy streets that were around the Victorian music halls, because in Shoreditch and Spitalfields, like you mentioned before, apparently those areas provided Londoners with lots of their clothing. There was like a real textile industry there.

Hazel Baker: We still got fashion streets even now.

Cat Bateman: Yeah, exactly. So half pound of tupenny rice. You know, it says pop goes the weasel, apparently a spinners weasel, which I never knew this, is a device that is used for measuring out a length of yarn. So they would measure it out. And then the mechanism would make popping sound when the correct length have been reached, it sounds like it was really boring and repetitive. And I think the spinners mind, obviously just sort of wondered, and it was brought back into play with the pop of the mechanism working. So I think that’s why it was such a natural thing for a song to come out of it.

But then apparently the third verse suggests that there might be an alternative origin to the sort of clothes manufacturing. And it was based upon Londoners using Cockney rhyming slang. And I love this cause this pub is actually near to where my husband’s office has been for ages. Yeah, cause apparently took pop is a London slang word for pawn. So like when you pawn on your items because you need your money and weasel can be traced back to the Cockney rhyming slang of weaselling Stokes. I love it when you say that’s right, Hazel, cause you’re the historian. But even a very poor Victorian London would have had a Sunday best coat. They would have had something, but they might not have been able to keep it because they needed some money. So they would pawn it. And that’s when it was like pop goes the weasel, and then they would like retrieve it on payday and where it says up and down the city road in and out the Eagle.

So the Eagle, as you said, refers to the Eagle Tavern, which is on the corner of city road and shepherdess walk, which I’ve been done loads of times. And I think they’ve even got a plaque in there saying a part of this nursery rhyme. So how amazing is that?

Hazel Baker: Brilliant! And there’s another plaque, well, it’s not even a plaque. It’s actually in the pavement on city road and it has the lyrics of pop goes the weasel.

Cat Bateman: I’m really grateful that you invited me on this because it gave me some real lovely time to look through some of the literature about all this and to learn some of the deepest stories behind them all.

Hazel Baker: No. Fantastic. I’ve learned loads as well, Cat. Thank you very much.

Cat Bateman: It’s such a pleasure. Thank you, Hazel.

Hazel Baker: Hope you have enjoyed this episode. I know we didn’t cover all London nursery rhymes, but we do have to save something for later.

Talking of later, this is our final episode. We’re going to take a break over the summer period. And we will be back again in September. For all of our patrons fear not. We have some exclusive content coming to you this summer. So have a great one and I’ll see you in September.