Host: Hazel Baker

Hazel is an active Londoner, a keen theatre-goer and qualified CIGA London tour guide.

She has won awards for tour guiding and is proud to be involved with some great organisations. She is a freeman of the Worshipful Company of Marketors and am an honorary member of The Leaders Council.

Channel 5’s Walking Wartime Britain(Episode 3) and Yesterday Channel’s The Architecture the Railways Built (Series 3, Episode 7). Het Rampjaar 1672, Afl. 2: Vijand Engeland and Arte.fr Invitation au Voyage, À Chelsea, une femme qui trompe énormément.

Guest: Maggie Coates

Guest: Maggie Coates

After working in Camden for 10 years Maggie thought that she knew the borough until she took the Camden Tour Guide Association course which uncovered the layers of history and meaning which make the various neighbourhoods of Camden so fascinating and lively.

so fascinating and lively.

Transcript:

[00:00:00] Maggie Coates: Hello, Hazel.

[00:00:01] Hazel Baker: Today I think we’ll be having a look at, addressing its architecture and its history, and also some of its fascinating exhibitions, because this is a bit of a hidden gem, and I don’t think many people would have actually really noticed this before.

So before we get into it, maybe it’s worth if you give our listeners a brief overview of maybe where 2 Temple Place is and its historical relevance to London.

[00:00:31] Maggie Coates: Okay, it’s 2 Temple Place, its address. So it’s not far from Temple Tube Station overlooking Embankment Gardens. And that’s the reason for it being there, really.

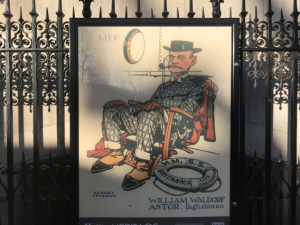

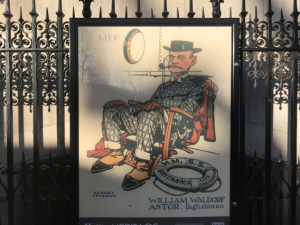

That whole area was redeveloped in the Victorian era. And previously all the industry, the buildings around there had been related to Pemside activities. And it was chosen by its owner William Waldorf Astor, as being a quite a secretive little place. When it was built it was Between two large buildings, it’s next to Middle Temple.

So there was a large Victorian library, which sadly was destroyed during the Second World War, but it had a tall, steeped, gabled roof. And on the other side was a very tall building that belonged to the London School Board. So it was a small building nestling among big buildings, even from the beginning.

And now it’s surrounded by modern office developments going up to the Strand. It is still a hidden gem, I think.

[00:01:30] Hazel Baker: It really is. It’s one of those ones that unless you really walk past and look at, you’re so maybe focusing on the little alleyway to get through to Fleet Street or focusing on getting to to Temple, you don’t really notice it.

And I suppose that’s part of the magic, isn’t it?

[00:01:46] Maggie Coates: It is, we quite often, I’m a volunteer there when the exhibition is open for four months of the year. And quite often people come in and say, I’ve often passed it, I’ve often thought, what is this building? Or I used to work round here, passed it every day, and didn’t even realise it was open.

So yes, it isn’t known very widely, but hopefully it will get more so as the years go by.

[00:02:09] Hazel Baker: Yes, indeed. And it has been host to a number of fascinating exhibitions over the years. And can you maybe share some of the most memorable ones?

[00:02:21] Maggie Coates: It opened to the public about 11 years ago when it was bought by the Bulldog Trust, a charity that was set up to run it.

And the first exhibition was about William Morris, which obviously there’s a link in time there because it’s a Victorian building. It’s at the same time as William Morris, which was pretty popular. In fact, there are still a couple of items in the building from that exhibition. And then each year the brief has been to introduce collections in the rest of Great Britain.

That. Highlights from some collections that aren’t well known around a particular theme. So we’ve had things like the gems that were collected by the cotton magnets of Manchester I’ll the Okay, the Cornish artists, so it’s had that brief. Last year we had a slight break from that because of the leftover from COVID, they weren’t able to develop the exhibitions, but this year we’ve returned with a exhibition I’ll tell you about in a minute.

The most popular exhibition they had was in 2019 when they tied in with the bicentenary of John Ruskin and they had. They were overwhelmed with visitors that year, maybe a little bit too much because it is only a small building, but it was a great chance to see some of the collections from Sheffield and the Lake District that he was linked with.

So that’s been their remit. And then they’ve got quite creative with the themes that they’ve taken up. Around different materials. The last one had a more worldwide brief. It was about the development of pottery in Africa and then the influence of that on the UK industries in the 20th century.

Always interesting, always something different.

[00:03:52] Hazel Baker: Yeah, pretty wide brief and the the bulldog trust you’ve just mentioned that’s why there is a sign of a bulldog hanging outside. That all makes sense now.

[00:04:02] Maggie Coates: That’s right, yes. People ask us that.

[00:04:05] Hazel Baker: It’s one of the clues in our temple treasure hunt, but there you go. Wonderful.

So you mentioned about the latest exhibition. Tell us about that.

[00:04:18] Maggie Coates: This year’s exhibition is called The Glass Heart and it’s about glass as a medium for both stained glass and standalone vessels, as they’re called. And it brings together the collections from Sunderland’s National Glass Centre the Stained Glass Museum in Ely and the Stourbridge Glass Museum, which were all centres for glass production.

And you think I didn’t know Sunderland was a centre for glass production, but when you think of Pyrex, which everybody had a piece of Pyrex in their house it’s it shows, that it was A delicate but sturdy material that had many sorts of uses and obviously as a medium for art as well.

So there’s some fantastic pieces that are complete flights of fancy and there are some that are very practical and commemorative, so all kinds of interesting things. For example, There’s a little glass boat that commemorates the, which was very popular in the Victorian era and was mass produced, commemorates the heroic exploits of Grace Darling and the lifeboat where she saved so many passengers.

And it’s also, there’s a exhibition has it could have a huge brief because obviously we have examples of Roman glass but they’ve chosen to take the starting point as the building of the Crystal Palace in 1851 because obviously it was made of glass, but also that was the start of the use of glass as an everyday material.

Stained glass enjoyed a big revival in that era. And as a practical, and as an ornamental kind of item, it really became popular. Lots of examples of how it’s created how it’s blown. And some contemporary artists as well. There’s a piece, for example, by Monster Chetwin. Do you know where else she’s got a an installation in London at the moment?

There’s one to scratch your head over, Hazel. Not at the V& A? No underground at Gloucester Road Tube Station. Oh! Yes, and it’s very interesting when you’re going through on the eastbound Gloucester Road line, her illuminated pieces all along the side of the track there. That’s a, that is a space which is normally used for art installations.

And she has one there she’s a very creative person and has turned her her skills to glass making as well.

[00:06:39] Hazel Baker: Fantastic. I do love glass as a, I’ll say, art form or medium. I suppose when you talk about the Victorian stained glass, a lot of people don’t really realise that a lot of the glass that we see in our churches now is Victorian, thanks to the Cromwell years and having to rebuild some of our history on that.

I remember one of my best times of going to Venice was to go to Murano and have a look at how they made their glass there.

And I bought two fantastic vases, which still bring warmth to my heart when I look at them now. It’s a gorgeous the way that light hits it and to see how it’s used over the years. Is absolutely fantastic. So I’m looking forward to seeing this one. Now you mentioned about the Astors.

Do you want to get us into why the strong ties and describe the, of the Astor family with

[00:07:30] Maggie Coates: Two Temple Place? Yeah, sure. The building was commissioned by William Waldorf Astor who was the third generation of the Astors. The original person that founded the Astor family was John Jacob Astor, and he emigrated from Germany, and he made his money importing, exporting furs, beaver furs.

And he made so much money that his son continued and built and invested a lot in buying lots of land in Manhattan and became the landlord of New York City. And so when William Waldorf Astor inherited the fortune from his father in 1890. He was known his father, John Jacob Astor, had been known as the landlord of New York.

Unfortunately, a lot of those buildings were slums and tenements, but he still made a lot of money outta them. And that made William Waldorf Astor Reputably, the richest man in the world at the time. Oh. But he had been based in New York, as all his family had been, and he had a couple of unfortunate incidents, which drove him to find a new home, and he came to London for example, he had tried public life.

He’d been a senator briefly, but at that time the press was very looking for scandals, looking for headlines and they found him to be rather dull character on the public platform and they ridiculed him and he was a quite a shy man and he found that ridicule very hard to take.

Also in society. He had a little falling out with his aunt, who insisted she was the Mrs. Astor, and there were no other Mrs. Astors to be had, and of course society in those days was so around status and money that was a downside. And also he worried about the security of his family.

There were quite a lot of kidnappings, children’s kidnappings and so forth going on. He decided to relocate his family’s wife and his five children to London. And of course he had lots of money. So he bought himself a very nice house in Carlton Terrace. And he decided he needed an office building and the site of Two Temple Place would be ideal.

And he set about, he gave the brief to the architect John Loughborough Pearson. And he said money no object here build a suitable building. And he also was very clear about the security of the building. He was pretty hot on security. And in the basement, for example, there used to be a huge vault that, covered most of the basement and there were strong rooms where all the documents could be held because he ran we just invented the telephone in that era, which is again, it’s celebrated in the house and cables and communication across the Atlantic was possible.

So he was able to run his entire business empire from London. And that was his little fortress. And there are touches of a fortress, medieval castle in the design. There’s crenellations along the outside. There’s a little tower, which is where the staircase is. So it has little gothic touches.

Although the style is a bit of a mixture of architectural styles from that era.

[00:10:39] Hazel Baker: It isn’t it? It is rather romantic, isn’t it? It is. It’s a romantic castle. It’s funny what you’re saying about John Loughborough Pearson really because It’s beautiful romantic architecture, what we can see at Two Temple Place.

But knowing that he did so many churches and cathedrals, Peterborough being one, Leicester another, you can see that influence in this building design, can’t you? And it’s beautiful for what, was initially an office.

[00:11:10] Maggie Coates: It is. When John Loughborough Pearson was given that brief, he was told, money no object, and he spent 250, 000, which at today’s value they say is about 10 million, so it’s certainly very lavish decoration inside, which I’m sure we’ll get on to, but the outside is a sort of mixture of styles, and also incorporated Waldorf’s idea of Security.

He was very hot on security. He had a big vault. He had a huge vault in the basement. He had lots of strong rooms. And he, although he didn’t officially live there, he did have a little sanctuary there where he had a bedroom and a bathroom and of course in the basement there were servants, a housekeeper and so forth that would have catered to his needs and when his wife died he pretty much permanently moved in there.

He said he felt more secure among all the vaults and the strong rooms and there was a little court case where he wanted to be registered as a Westminster resident at that address and he won the case and he was able to cast his vote as a resident of that area. Fantastic.

[00:12:20] Hazel Baker: Who would have thought, Dave?

If we’re talking about the outside with this kind of, I suppose you can say, gothic revival, it is beautiful. How would you describe the interior?

[00:12:31] Maggie Coates: I would say it’s a symphony in wood because wood is the main material that’s used. William Waldorf Astor doesn’t seem very keen on works of art, unlike some of his contemporaries who collect a lot of paintings.

He did collect sculpture, but he didn’t want any representations on his wall, on his decorative scheme. Wood is the main thing. And as Go up the building as you go from the ground floor to the first floor, you can see a change of use because the ground floor is paneled in oak quartered oak, which has that lovely grain.

And that would have very much the place where his clerks worked where so he needed to be quite plain wasn’t distracting. But when he came into the building, he came through the double doors. Into a vestibule which has of course a beautiful marble floor made of coloured gemstones very much similar to his other mAstorpiece, the Fitzrovia Chapel using the same craftsman, Robert Davidson was the craftsman on that. And so you come into this sort of Roman style floor. He does mix his eras. And then the first thing that Astor would have seen was his magnificent mahogany staircase which he indulged his love of literature.

It’s the first time you see it in Temple Place. It has these beautiful series of statues. Carved by John Nichols, who represent the characters from the Three Musketeers, which was apparently William Waldorf Astor’s favourite book. So we start with D’Artagnan and then on the left hand side we have the other musketeers.

So we have Aramis, Artos, and Portos. And on the other side we have other characters M’lady Winter, and Barazun, who illustrate the whole series. So the staircase itself is sometimes overlooked because these statues are so amazing.

They’re about 18 inches tall and full of character. Aramis, for example, is looking quite interested. Apparently, if you look , one of the statues has a thumb missing because they could take them off to clean them over the years, but I’ve never been able to spot the missing thumb.

So it’s done, but it’s beautiful detail on those statues. And as you go up the staircase, you come onto the balcony of the first floor, which is amazing. The pillars are made of ebony and that length of ebony is not available now because ebony is really a bush.

It’s not a tree. It doesn’t often grow that tall and it’s so rare they couldn’t be replaced if they were ever lost. And we had the start of the use of more interesting woods. So though we’ve had mahogany. On the first floor there is the panelling is pencil, wood, cedar. Which strangely is from the juniper tree, but it’s called pencilwood cedar.

If you get very close and sniff it, it does smell of pencils. That’s the plain paneling. But above the paneling, because the stairway is lit by a lovely stained glass by the firm Clayton and Bell, which is a reflection of this exhibition being about glass. We’ve got all kinds of carvings there.

We’ve got carvings, six figures that represent three of William Waldorf Astor’s favourite American novels. So we’ve got Last of the Mohicans represented, Scarlet Letter, and Rip Van Winkle. So six really large statues, then above that, there are some more carved friezes which each represent a different Shakespearean play.

So he’s mixing English and American literature because those were his favourites. And then you go on to the library, which that side of the building is quite shady, particularly when the Middle Temple Library overlooked it. They decided on a satin wood, which is a very shiny wood, a very light coloured wood, as it would amplify the light in that room.

And these carvings are done of walnut. And there was once a lovely marble fireplace there, but that was removed after the war. But it’s still a lovely room and it was Astor’s private library where he used to retreat to in the afternoons, I think. I picture him there with, with his cigar and his brandy or whatever, perhaps having a little nap in the afternoon and a lovely room when the sun shines on that Suttonwood and the little walnut.

They’re a little, there’s a, although all the books have gone the bookcases are still there and they’re used for the exhibition. They’re an excellent, cubby holes for little exhibits to go in. And above them is a line of little cherubs, little putty, who represent the modern art. So although one has traditionally got a little globe another one’s got a microscope to show the modern science art.

It’s a lovely little room. And then the main hall, the largest hall, of course, is It’s a stunning visage in every aspect of it. It’s so wonderful. It’s a hammer beam roof. You mentioned John Loughborough Pearson, very much sort of a medievalist, loved the old churches. And for a time he was in charge of works at Westminster and he renovated Westminster Hall and obviously he enjoyed the hammerbeam, the original medieval hammerbeam roof there and he recreated a slightly smaller version in this room.

So it’s got a magnificent hammerbeam roof but of course it doesn’t stop there. The beautiful panelling. There’s carved fireplaces. What strikes visitors usually first is, there’s a frieze of gilded faces around the top of the room. And they’re completely random. They’re just characters that William Waldorf Astor loved.

They’re either real people or imaginary people. So you’ve got Ophelia from Shakespeare but you’ve also got Count Bismarck you’ve got, you’ve got all the sort of heroines. He liked a tragic heroine. You’ve got all tragic heroines, Mary, Queen of Scots, and so forth, and they’re in no particular order, so you’ll get someone from the 14th century next to someone from the 19th century.

They’re not grouped in any way, but there originally were 50 of these gilded faces around. A few of them were lost during the war. The end of the building was damaged and was reconstructed. And then above the gilded the freezer faces on the hammer beam roof, there’s a series of statues again which are from Ivanhoe by Walter Scott.

So you’ve got Bade Marion and Robin Hood and so forth. And the story goes with those that the The the carver the craftsman that created them just did them in wood originally, but Astor’s eyesight was was fading a little bit by this time, so he asked her to have them gilded so he could see them more clearly.

And the carver didn’t, wasn’t so keen on that idea. And as a little kind of reminder, there’s a beautiful door and above the door there’s an angry puttee, a tiny little cherub who’s got his arms folded and is looking rather cross, which is not, and his pose isn’t a normal pose that you’d see a cherub in.

And below the cherub is a beautiful gilded door which was which was done by George Frampton. Who you may know, he did Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens. Oh, of course. Yes, so this is three dimensional raised metalwork. And it depicts nine maidens of the Arthurian legends. So you’ve got Guinevere and you’ve got the Lady of the Lake. And they would have been directly opposite because the photographs show that Astor had his desk facing that door and all his objects and his collections around him.

He would have had some of his statues and he even had sort of mannequins in medieval dress around him as well. I don’t know. It’s a strange that the the pictures show of his time there. And in the next room, which is now the shop that room was entirely a strong room. So it has no decoration at all.

But now we have some nice William Morris wallpaper on there. And that’s the part that’s open to the public. There are the little nooks and crannies that you can see into that are still used as offices for the Bulldog Trust.

[00:20:28] Hazel Baker: It sounds like a very personal building project.

[00:20:33] Maggie Coates: It was, it absolutely was.

He really indulged his love of literature and how he wanted to be surrounded, because he could spend whatever money he liked. And that may be why his family sold it after he died. He died in 1919 and it was empty for a couple of years and it was bought in 1922. And luckily for us this comes, to the It’s your other question really about how it’s been preserved over time.

We, it’s really had three very careful owners until the Bulldog Trust. And I wonder if the family decided to dispose of it partly because they moved some of their offices back to states, but because it was so personal. whether some, whether these descendants really took that style.

And of course, fashions change, tastes change. But it was very ornate. The first guardians of it, first custodians, were an insurance company, Sun Life of Canada. But they were only there for six years, till 1928. And then it was bought by the Society of Incorporated Accountants and Auditors.

And it worked well for their uses because they were able to not only use it as offices, but also as a social space for their members which of course Astor’s Rooms really lent themselves to that as well. And we’re lucky that they were the custodians during the Second World War they took away they saved the stained glass they preserved it, and they rebuilt very carefully after the war in very, in a very similar style to what had been before and preserved a lot of it through that.

One thing they did change was the door, the original doorway to the building was completely destroyed by an incendiary bomb just outside. And that had been, again, very personal. It had the Waldorf family crest above it. Because William Waldorf Astor was very conscious of his heritage. He’d created this family crest.

So it was, and it added to the sort of Gothic, baronial look at the building. When it was destroyed during the war, it was simply replaced with a much simpler wooden doorway and the window above was enlarged to compensate in the sort of balance of the building. And a new wing was added, but so subtly done, so well done, that you wouldn’t really know unless you could pick out slightly more modern carving.

The accountants were very good custodians but they gave up the building in 1959 to the pharmaceutical company Smith and Nephew, inventors of the elastoplast. That’s where they made their money. But again, they were very good custodians. They did change the entrance foyer area. They updated it.

They gave it a couple of modern 1960s touches. New lamps a seating area which is upholstered in reindeer leather. And a lovely pendant clock, which is a very modern sort of style. But it all works quite well in the style in that area. And that area wasn’t particularly decorative before. And they did little touches to the building.

They put fire guards on the radiators. It was one of the very first buildings to have central heating. Right when Astor built it, it was one of the first buildings to have electricity. Which is celebrated in the little lamp. post outside. And so after Smith and Nephew they they were there from 1959 to 1999, and then it was bought by Sir Richard Hoare, who established the Bulldog Trust to look after it.

We’ve been lucky that the custodians haven’t changed very much, and also they have maintained the fabric of the building, which any historic building needs that to keep going.

[00:24:06] Hazel Baker: Yeah, that’s very good. Especially as you were saying, a) it’s very personal, but also as styles and requirements of an office building change.

So we’re very lucky to have this one. Now, there’s something that you said at the very beginning about the choice of location for Two Temple Place. But why did Astor choose that particular location.

[00:24:30] Maggie Coates: I think he was quite impressed that it was next to Middle Temple. A lot of history there. Astor was a complete history buff.

As well as his original townhouse, Carlton House, he bought Cliveden, which he renovated. He bought Hever Castle, which he renovated. He had quite a thing about Anne Boleyn. I think she was, appeared in quite a few of his things. And apparently she, he even had the rosary that was supposed to have belonged to her. I think he liked the historical aspect of it being next to the Middle Temple. As I say, originally, it was next to the library that was destroyed during the war, which was a huge Victorian building with a steep gable. And that kind of influenced the look of the building when they, when he was working with his architect to reflect that kind of historic outlook.

He was, he qualified as a lawyer himself. He studied law. So he perhaps liked the fact that it was law, but also I think it was because that land was quite reasonable. It was new land in the, embankment in front of it was created in the 1860s to take the sewage pipe and the district line underground.

So that was new ground. That was going to be land, always going to be landscaped as a garden. And it has many statues in it as well. I’m sure that would have appealed to Astor. And so this land, it made defunct all the riverside activities that had taken place north of that area. So I think the land was quite reasonable because it, it was out of fashion.

And its uses had changed, there was, nobody, perhaps, but him had the foresight to see it would be such a lively area linked to these other nearby facilities. I think it was the land came up at the right point, and it had the historical links that he liked. It was just called Approach Road when he bought it, it was just seen as a road that you approach Middle Temple with.

It didn’t have its own character, but I think that his building helped to, and there are other professional buildings in the road as well, helped to give it a little bit more interest and stability.

[00:26:24] Hazel Baker: I suppose also the location is helpful when he purchased the Pal Mal Gazette and and although the printing presses, et cetera, the observer on on Fleet Street, he was, it all, wasn’t he?

[00:26:36] Maggie Coates: He he, I think he had, he loved literature, he had literary aspirations. He wrote novels himself, didn’t he? And they were quite well received. Apparently the first one he did have published anonymously, so it wouldn’t, it would have, it was, it’s reviews would be real but of course he did fall out with the man, with the editor of the Palma Gazette, because he wanted to publish his own stories in it and he created the magazine so that he could publish his own stories.

So buying the Observer was a thing later in life, once he was established, to add to his empire.

[00:27:08] Hazel Baker: There’s a connection you’ve mentioned with Downton Abbey, because you mentioned about George Frampton and the statue of Peter Pan, which is in Downton Abbey but also Two Temple Place and that beautiful staircase is used when Lady Rose gets

[00:27:26] Maggie Coates: married.

Yes, it stood in for Caxton Hall, and you do notice I jump up and down now when I’m seeing a TV series or a film, there’s a corner of a staircase or an office used.

I think the most well known use for filming was Bridget Jones’s diary. It’s been filmed there and in one of the early films she’s sitting waiting. I think it’s supposed to be a doctor’s waiting room She’s sitting under one of the beautiful stained glass windows in the main hall And with the light coming behind her, but they did use it for later ones But you often just see a corridor a panel corridor I enjoyed the use it was made of a recent film of blithe spirit with the Judy Dench played Mrs.

Arcati, the medium. And she comes to the offices of the Society of Mediums or something. And it’s the, Astor’s main office. And it was in its Victorian heyday. So it looked scrumptious. Even dressed with fake office accoutrements. It looked it looked very impressive for that kind of organization.

Yes, apparently Batman and all kinds of things like that. been filmed there. Because people wonder as well, the building is only open four months a year for the art exhibition from January to April. And it’s closed the rest of the year. They’re encouraging more open days to happen.

Any fundraising they do through the building being open, selling souvenirs and books and things, any donations people make. Help the fabric of the building itself just for them to put on more art exhibitions, more activities. In the summer they open for a couple of days. Family trails, they have some artworks developed for families.

And, of course, they open for Open House in September. But apart from that, the rest of the year they’re used for private functions weddings, very popular, obviously, a magnificent setting for a wedding corporate functions, and filming. This last year with the writer’s strike, there hasn’t been so much filming, but it’s certainly on the list of places that are well used for filming.

And because it’s closed, it’s obviously easier to set up a filming apparatus there.

[00:29:24] Hazel Baker: Yeah, of course. If anybody hasn’t been to Two Temple Place, then now is your opportunity to go. Maggie, when does, the exhibition is already open, when does it close?

[00:29:37] Maggie Coates: It finishes at the end of April. Just after Easter it closes.

It’s open Tuesdays to Sundays. The opening hours this year are gonna be a little later, so it opens at 11 and stays open till six. And the idea is that people perhaps can come after work shorter hours on a Sunday and it’s open late every Wednesday. And during the late night Wednesdays we actually sell alcohol beer, beers and wine.

And there is enter, there’s. entertainment. There’s a full program of activities going on in the evenings. There’s also workshops and talks. And if you look on the website for Two Temple Place it’ll tell you all about those and how to book. So there are tours down off the building as well. You can book for those.

[00:30:21] Hazel Baker: Excellent. Plenty to look forward to. We’ll put a link to all of that in the show notes as well. So you’ve got everything all in one place. Maggie, thank you so much.

[00:30:31] Maggie Coates: Oh, thank you, Hazel.

Guest: Maggie Coates

Guest: Maggie Coates so fascinating and lively.

so fascinating and lively.