John Wyatt Greenlee, also known as The Surprised Eel Historian, is a medieval historian, who’s work focuses primarily on maps, spatial history and eels.

Eel plaque on Tower Bridge. Credit_Hazel Baker

Eel plaque on Tower Bridge. Credit_Hazel Baker

Show Notes: Dutch Eel Trade in Medieval London

Hazel Baker: We’ve got an interesting topic for you today, listeners. It is the Dutch eel trade in London.

John Wyatt Greenlee: That’s a sort of fascinating, a really long-standing trade that goes back to at least the 14th century and maybe even before. So I’m happy to be here to talk about it.

Hazel Baker: You’ve just touched on the origins of this how did it all begin?

I hadn’t even made a connection with the Dutch and eels.

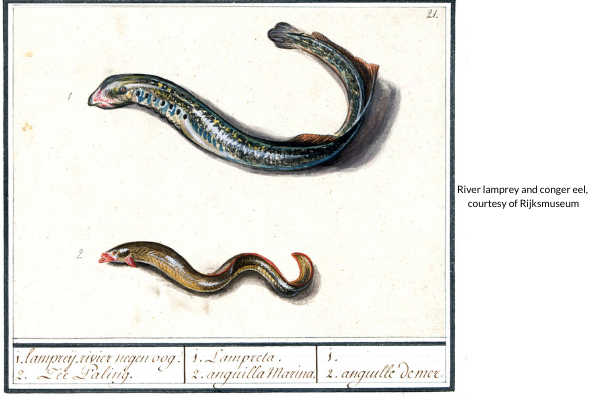

John Wyatt Greenlee: Pre-modern England has this really long history with eels. They’re a terribly important part of the sorts of diet for everybody from peasants, all the way up to Kings and an important part of the culture as well.

They get used to a pseudo currency in the early medieval England with people paying taxes and yields and they show up in art and literature and all kinds of. And it boils down to the fact that they’re just eating a tonne of eels. Somewhere in the early 14th century, so pre black death a little bit the English start importing eels from the Dutch to mostly to the south of England and primarily to.

And it’s not entirely clear why this sort of shift happens. There are some reasons I know for a fact. So one of the things that has happened is that the Dutch have spent the first part of the 14th century heavily mining their peat bogs. And one of the things that’s happened is that they’ve mined their peat bogs to the point where they’ve created lakes essentially. A huge part of their inland territory is becoming lakes and it they’ve basically made it into a fantastically verdant eel habitat. And so the Dutch wind up getting more and more eels than they had previously had. One of the things that happens to the black death in 1348, 1349 is in Holland is there the flight to the cities that a lot of people leave the countryside and go to the cities

which is a little bit of the reverse of what happens in other places like Italy, but they abandoned a lot of these sort of those inland territories and the these ponds that they made have been managed by weirs and dykes and dams and flood gates. All sorts of things and they start falling into disrepair and the people that wind up getting them tend to be sort of merchant families from big cities, from like Amsterdam.

So they wound up buying these inland territories that are really inexpensive. And then, so they wind up in control of these canals and waterways and things. And one of the things that they do with them is they start fishing the eels and then you wind up with these merchant families in Amsterdam and other cities who basically get control of the eel trade.

And they have more eels than the Dutch want to eat. And so they start looking for places to ship them and they wind up shipping them all over Europe, actually the Dutch trade eels broadly in, into the interior of the continent, but also they start trading them to England. They start doing it initially dried and preserved eels that they’re trading, bringing across in barrels.

Hazel Baker: They’re alive? They’ve got to be live?

John Wyatt Greenlee: Not initially, they’re preserved; dried and then salted and stuck in barrels. You can transport live eels in barrels cause they can live out of water. And so you can pack them in between layers of wet hay or Moss and they can live a while.

But initially what they’re trading are salted. And so the first records we have of this come from the 1360s really from London. But they also make it clear that these are the, it’s an arrest record actually, I think. If I’m remembering that or a petition to the King, but it’s it’s clear that the person who’s making this petition into the arrest has been doing it for a while.

So the records start in the 1360s, but it’s clear that they’ve been doing it for a while before that. And so initially they’re bringing them over it in barrels lots and lots of barrels of eels. And then they switched in the 1440 by the 1470s. They’re starting to bring them over, live in the sort of hold of

sort of Dutch water ships where they’re basically the hold of the ship. It’s like a giant floating aquarium. So the hold of the ship is full of water and it’s got holes in the side of the ship that let water flow in and out. And these are either really small holes or they’re bigger holes that have screens on them.

And so the eels can’t get out but you get water flow through that keeps the sort of the water fresh and that helps the eels live longer. And so they’re putting the eels in the holds of these ships and then bringing them across the channel and up the Thames and parking them in the middle of the Thames off of mostly of Queenhithe but also Billingsgate, but Queenhithe is the first place they park and sell them and they put them, they park they’d parked the ships in the middle of the Thames. So you get water flow through them. And if you want your eels, you take a smaller ship out to them and they pull up the eels and measure them out. And this approach works well.

And it wouldn’t work with just about any other fish because eels can transition between freshwater and saltwater relatively easily. I think you have to give them a little bit of adjustment period. So they leave the ships at the, in the estuary of the Thames for a couple of days and let the eels adjust and then bring them up.

But you couldn’t do that with most other fish because they can’t make that sort of transition. But you can with eels

Hazel Baker: I’m thinking about some salt water and fresh water and where Queenhithe is near. Blackfriars bridge. That is where traditionally the freshwater then started the terms. So Queenhithe, there’s just a little bit before that where that transition begins, we’ve got an interesting choice for them. But. Queen hive with being the a very busy and also very smelly Wolf as well. So that might have been another reason, but it’s how did they sell them in sense of what you said they were measured them in length? Was that how they did it or was it by weight?

John Wyatt Greenlee: By weight, I’m sorry. Yeah they measure them by weight. See, you took a ship out of the small ship, out to the Thames and they would pull them up with a net and weigh them out and. And you take them back to shore with you.

Hazel Baker: You get it super fresh. Don’t you and what these to be businesses buying them in bulk or would it be individuals or households buying the eels?

John Wyatt Greenlee: Both. So a lot of, it’s a little hard to tell from the earlier period we know from much later cause these ships stay on the 10th. W with the exception of a small break in the 17th century this date on the 10th until 1938 doing this. We know from a lot later that that a fair amount of the business buying eels from these ships is going to street vendors.

So either fish merchants is coming out and selling to the street vendors or street vendors themselves going out to the ships and buying them and coming ashore. But also there’s individual people, individual households who are going out. If you don’t want to get your eels from a street vendor, you don’t want to get you want.

And you can take the time to do it yourself, then you can go out. So it’s a little bit of everything. I think I said, that’s hard to tell exactly what’s going on in the 15th century because we don’t have a lot of records, but we do from later. So they’re selling to whomever, wants to come out and buy them. I think.

Hazel Baker: What was the appeal of eels?

John Wyatt Greenlee: So that’s an interesting question, right? We don’t tend to eat a lot of eels anymore. And so I get that question, especially in the United States where I live, we eat almost none of them outside of, eel in your Nagi and Japanese food. I think there’s a bunch of things for pre-modern England, right?

They are first off. It’s a really abundant food eels have traditionally historically made up. As much as 50% of the fish biomass in the downstream sections of rivers in Europe and England. And so there’s a huge number of them. They, so they’re abundant. They are a really good source of protein and fat.

And so they wind up being a poor person who later they pick up that, that sense in. 18th century plus, but early on everybody’s eating the bureau or records of Kings eating eels and nobles, and did one of the most commonly purchased foods in noble households eels are. And, but all the way down to the peasants to serve, everybody’s eating them.

They’re just a really important part of the cultural diet And they are a religiously important food, too. There’s a bit in the medieval period. There’s in the high medieval area. That era there’s about a third of the year are fish days, right? Fish days where you’re only supposed to, you’re not supposed to eat meat, but you can’t eat fish.

And the reason you’re not supposed to eat meat is because the medieval definition of meat is basically something that lives on land and has hooves is a really rough definition, but you’re not supposed to eat that because meat, it comes from animals that reproduce sexually and during lent or other of these sort of church holidays, you’re not supposed to be thinking about sex at all.

Thomas Aquinas is pretty clear about this. He says cows and things like that make you think about sex, but fish doesn’t so much. And eels are particularly sexless kind of fish in the medieval imagination.

They Understand how they reproduce. And I think, and coming from Aristotle in sort of antiquity this idea, they have this idea that eels reproduce asexually that they have a spontaneous reproduction of one sort or another, I’m not quite sure what it is, but so eels are a fish that doesn’t produce sexually at all.

Doesn’t have anything to do with sex in that perspective. So they make for a really good food for. For these fish days. And in England. So I said about a third of the year, our fish day spend the time you get to the high medieval period. And these continue on after the reformation and are actually enforced more vigorously after the reformation than they were before, because there’s a fear that if they get rid of the fish days, that.

Sort of be a financial crisis for all of the fishmongers and fishermen and everybody else. And even after the reformation, they what are essentially Catholic holidays, right? Get enforced more vigorously than they had been previously as for entirely secular and economic reasons.

Hazel Baker: Yeah, I am trying to get the the economic reasons. And I think it’s important to, to remember about the, how religion really moulded people’s lives. There was a structure there as well, what they can and can’t eat. And of course the rich people ate the meat anyway, because they could afford to pay the fines, nothing changes there does it.

John Wyatt Greenlee: No. And it’s medieval people are like people today a lot respects, right? There are going to be people who follow the sort of religious guidelines to the letter and live their lives by them. And they’re going to be people that don’t at all and the whole spectrum in between.

Hazel Baker: And have you come across any decent recipes?

John Wyatt Greenlee: There, yeah there are a number of medieval recipes that I can point to. There’s a really fancy one called reverse the reverse deal, which doesn’t show up in England, in English cookbooks very often, but was more a French recipe where you take the eel and and filet it.

And then. Turn it inside out and stuff the inside with bread and dates and fruits and spices and things and whatever tasty things you have, and then you sew it back up and cook the entire thing in red wine. Then I’ve always thought that sounds really fantastic. A lot of medieval recipes for yields are.

And then. Turn it inside out and stuff the inside with bread and dates and fruits and spices and things and whatever tasty things you have, and then you sew it back up and cook the entire thing in red wine. Then I’ve always thought that sounds really fantastic. A lot of medieval recipes for yields are.

Medieval recipes. Aren’t like modern recipes. They don’t give you step by step instructions. So a lot of times the recipes are like, cut the eel, cook it, put it in the bread. They assume, they’re assuming that the people reading them are are working, are sort of professionals or people working in kitchens already.

And like it’s they’re reminders more than like instructions for people that don’t know what they’re doing. But they eat eels in a lot of different ways, a lot of eel pies, which is still relatively common. Eel pie and It looks like probably a lot of the sort of more simple recipes are to serve cutting up eel rounds and cooking them in a pan with some basic herbs.

They get put in fish stews and pies and things smoke deal that are the most common for, like I mentioned earlier that people pay their rent in eels. And usually those are paid once a year and then somewhat large numbers and often the monasteries and. Those eels are almost always salted and smoked.

And medieval smoking is a cold smoking process, which is slower and leaves you with a much less tasty meat at the end of it. So those that eel tends to get put in stews and things like that, where you can disguise the. The most well-known eel recipe, probably in England at this point, is jellies eels, which is not a medieval thing at all.

It’s a, that’s a 19th century invention. So they didn’t, that’s a question I get a lot. Is did they eat jelly deals and answers? No they didn’t that comes along a lot later.

Hazel Baker: I find it all fascinating really cause I’m trying to work out in my head. How eels are fallen off the, if it was quite a usual, main staple of. Diets. And as you quite rightly mentioned, we’ve got we’ve got eel pie and mash stalls all over London, reducing sadly, but it’s an acquired taste.

Isn’t it? The eel for me, it’s not the taste. It’s the the texture. And you saw my face when you mentioned jellied eels. Oh, I just can’t do the jelly at all. It’s funny. Isn’t it? How things change?

John Wyatt Greenlee: It is so I’ve never had jelly deals either. And I have to admit that looking at pictures of jelly deals puts me off.

Yeah. At this point eels, I think in England have a real lower-class sensibility. The it’s an east end food. It’s a lower food or a tourist food at this point, right? Yeah, you go to, the East End of London you should have some jelly deals. They pick up that sensibility from about the sort of the 18th century on where they start getting this sort of lower-class sensibility.

And I think. I think it has to do, and I’m not certain about this, but my guess is that I mentioned that these ships, that these are the Dutch ships trading eels in London are the primary way that Londoners are getting their eels and they are for a really long time. But there’s about a 15 year period between 1666 and 1681, where the ships aren’t on the Thames anymore.

This is right in the middle of the Anglo Dutch wars. And they get kicked off because the the parliament, the king of this idea that that they want to reinvigorate an English sort of eel fishing. And so they, they ban foreign imports eels. And so the Dutch ships leave and they’re gone for about 15 years now.

It turns out that they, the English can’t replicate what the Dutch are doing among other things. They don’t know how to make the ships. There’s a really fascinating anecdote that. Has an eel purveyor, a purveyors of fish and eels, and he wants him to bring eels over to get eels

and the guy has to get permission from parliament to go across the channel, to, to the Dutch, to buy these ships because he says that nobody in England knows how to make them. So the Dutch are the only ones who know how to transport live eels in bulk. And in in. 1679, 1680, you get a series of petitions to parliament, basically saying, Hey, we need to let the Dutch back end because like we really we can’t supply our own eels

and part of what’s going on there too, is the English are draining the fens and so they’re destroying their own native eel habitats. So in 1681, they allow, they sort of parliament passes an exemption and lets the Dutch come back to the Thames. Everybody else is banned from import eels, but the Dutch are okay.

So they come back and this time to Billingsgate rather than queen height and they park there. And like I said, they stay there until 1938 selling eels from these ships anchored or chained in the, just off the, just off billings, get in the Thames. I think that 15 year period is a real sort of breaking point in a lot of interesting ways where the Dutch aren’t there and they’re not selling eels and you will fall off the diet a little bit in London.

Because to that point, eels show up a lot in metaphor, in art, in place. They’re in a lot of like early modern place. Shakespeare mentions eels more than any other fish. And there’s a real hard break after that, where they suddenly stop appearing in literature and in metaphor and all sorts of things.

And I really think that sort of moment where there’s 15 moment, it’s a, I’m a medievalist, so 15 years is a moment. But the sort of moment where the Dutch aren’t on the Thames anymore for the 15 years, I think really makes a shift in, in how people are thinking about and can consuming it yields.

And they come back and after that, after the Dutch come back, the eels really pick up the sort of lower class sensibility that. That they stick with through the present basically. And through the 19th and early 20th centuries, the poor people in London were still eating a lot of eels but with the sort of advent of better refrigeration and better transportation you get and broader varieties of food, you get more availability, the more people of different kinds of food.

And, as always happens People want to live, like people they see as better than the right. So if I can eat like the rich people, I want to eat like the rich people. And so there’s a, in the early 20th century, there’s a move away from eels and are selling eels on the 10th until the 1930s, but the sales keep dropping off and getting less and they leave prior to world war two.

But by the time they leave, they’re really not doing a whole lot of business. And the ships don’t come back after serving the 1950s, the. Importing yields to London, again, through basically through, mostly through shipping them to Yarmouth and bringing them in through refrigerated trucks. But it’s a really small fraction of the business at that point.

So I think it has to do with sort of class sensibilities and sort of availability of other kinds of.

Hazel Baker: Yeah, I suppose if you take it out of the the people’s normal food chain and when it’s re-introduced well, they’ve obviously found something else to eat for 15 years. That’s a long time.

John Wyatt Greenlee: Yeah. Yeah. There’s an entire generation of kids that grew up not really having eels in London and grew up with not having eels as this potential part of the diet. And it gets tricky. London drives so much of. English to cultural production that it’s sometimes it’s easy to look in the past, especially to look at things coming out of London and assume that it’s what’s going on in all of England.

And that’s probably not right. But this is the English would probably in the countryside are probably still eating eels on a pretty regular basis. But it does really change how broadly, how the culture is looking at the.

Hazel Baker: And do you know what they did eat instead for these 15 years of eels other than

John Wyatt Greenlee: English eels

I do not actually. That’s a really, that’s a fascinating question. Other things obviously, and apparently they pined for their emails cause they petitioned to get them back.

Hazel Baker: They petition whom, the king?

John Wyatt Greenlee: Parliament. Yeah. There’s a couple of petitions to parliament asking to, to allow the Dutch to come back because they can’t get enough eels native eels into London on their own.

Hazel Baker: So we had self confessing eel

John Wyatt Greenlee: yes. Yes,

Hazel Baker: that’s fantastic. So I love this idea of the invention of the Dutch, once bringing over salty deals and then going, you know what we can do bulk and also minimising the. The process of preparing the eels by not hitting them over the head and not salting them saving on salts and barrels.

And let’s just create one big barrel. I E move them all over. That’s ingenious, isn’t it?

John Wyatt Greenlee: It is. And it’s it those water ships are ships that the Dutch used for a whole bunch of things, including they do use them for inland trade for fish like this and taking water out to to big ships in the harbours.

Yeah. And somewhere along the line, they, somebody has the brilliant idea that, oh, we could, yeah, we could put the eels in these and just take them across the channel and do it that way.

Hazel Baker: That’s fantastic. And what’s the Dutch word for them? I’m suiting, not wassar boten?

John Wyatt Greenlee: No Pauling and my Dutch, I can’t pronounce Dutch at all.

It’s palingaken. One of the ways you can tell that the Dutch become how important the Dutch yield trade is in London, is that starting in the 15th century? So our mid 15th century that word palingaken starts to be the way that the parliament describes eel sellers in London. So they’re using the Dutch word to describe it.

Hazel Baker: I’m going to have a little look now and see, and do the Dutch never convince themselves to eat their own eels

John Wyatt Greenlee: they do. They eat lots of eels actually, but they have so many more then they can eat natively, I think. And it becomes a really important part of their economy as well. This eel trade.

They trade deals all over England. And as they start to drain their own inland spaces, they start doing a lot of fishing in Danish waters in the sort of straight between the, the dangerous straight between sort of Europe and and Scandinavia. And then bringing those eels back down to Holland and keeping them in basically big pins in before they can take them wherever they need to take them.

Hazel Baker: Fantastic. And have you got any particular, favourite artwork of an eel because I know you share a number of them on, on, on Twitter, but for London specific, have you got, have you got anything that you were, that you particularly like

John Wyatt Greenlee: I do actually.

A category, and this is the thing that got me interested in eels in the first place is they show up on maps of London, these sort of really nice big scenic view maps that are, done by Hollar and Norden and some other people. So starting in 69 you get these eel ships on these maps and there’s and Norden does one in 1600 that’s a couple.

And then Hollar, they show up on a bunch of Hollar things in his maps and his artwork of London. And they’re easy to spot because they’re always right off at Queenhithe. They’re always two of them together. Cause they get, they they park two of them at the same time. I got interested in.

At all, because I’m a cartographic historian by training. And I was looking at these maps of London and the ships stood up because they’re labeled eel ships. So you know what they are, and that’s really unusual. Everything else on these maps that has a label is. It’s a neighbourhood like Queenhithe or a big civic monument, like London bridge or the globe or something like that.

And, things that can’t sail away, like big native parts of the civic infrastructure. And then you have these ships what are these ships doing? Labeled sitting here? Cause they can leave anytime they want. And in fact leaving. Yeah. Leaving. In fact, they ended up being part of the, they have to leave.

They have to leave and come back. So they’re like a landmark. And then I started wondering why and that led me down just like tremendously long series of intellectual rabbit holes that at the end of the day, I ended up being an eel historian rather than the map historian. But it’s been it’s been fun.

So I think those that’s, I think the sort of category of artwork that I find. Of London eel art that I love most of the maps, especially the Wenceslas’ Hollar’s maps from the 1640s are just fantastic.

Hazel Baker: I have a copy here. So when I put the phone down, I’m actually going to have a look now because I have never noticed the eel ships.

So two together, do you think that was because one was coming with new stock and the other one had depleted stock and they were able to move old stock into the new ship and then that one can go? So you’re keeping it fresh?

John Wyatt Greenlee: No, actually it’s slightly more complicated than that. There are passing up river from London bridge is always tricky, right?

Because there’s only sort of the one space in the bridge where you can go. And so there are there’s legislation’s not the right word, but there are rules about for these kinds of ships coming in how many can go upstream to Queenhithe and how many can stay downstream at Billingsgate and you wind up with basically two at a time are allowed at Queenhithe

and then yeah, so they. One gets empty. The next one comes and swaps out and this, they wind up doing this at Billingsgate too. They ended up doing two at a time and it develops this really fascinating mythology in the 19th century that this idea that somewhere along the line, there was this charter for one reason or another.

One Monarch or another, it changes depending on what you’re reading that these these ships were granted a sort of free docking rights for as long as it’s a great story, right? They’re free docking rights. As long as the as the docking chains don’t remain vacant for more than two minutes.

So there’s this swapping out thing that happens. It’s a completely apocryphal story. But it’s a great one anyway. But no, so they, yeah, so they, they trade them in and out. And there’s only two at a time allowed, especially at Queenhithe because they have to pass up through the bridge.

And Norden and Visschers’ maps and Hollar’s always show two at a time and then holler, pints them. He really liked them, but he paints them in some other this other he does other artwork of London and you can see them on the temps because you can see. There is a particular tower it’s of a water pumping tower as well.

Yes, the square one and it’s really in Queenhithe and it’s really noticeable. Like it, it really marks the spot. And so you can tell in his paintings where his other drawings where the ships are, and there’s always two of them, right by those right by that tower. Holler really seem to enjoy them.

Oh

Hazel Baker: fantastic. I’m going to have a look at that map myself now. So I know exactly what an eel ship was, because I’d never heard of them before. So you make believe I’ve missed them.

John Wyatt Greenlee: Yeah. And Hollar painting ships are really realistic. They’re like you can get a really good sense of what they look like.

The earlier early ones. Norton’s ones are. Realistic to what the ships look like, but it’s fascinating. They they keep the same basic design for. You know what? 500 plus years the ships in the 1930s are basically the same ships that they were using in the 15th century.

They’ve, they’ve taken upside on the space in the back with a motor and an engine, but that’s it.

Hazel Baker: If it’s not broken, don’t fix it. Yup. Fantastic. Oh, John. Thank you so much. That’s been absolutely brilliant. I love learning new things anyway, but this is brilliant.

I’ve added an extra knowledge to my eel knowledge, and I thought we’re going to be talking about eel pie island, but of course that’s Henry VIII. So a little later on when it gives me excuse to talk to you again. Thank you so much. Really appreciate.

John Wyatt Greenlee: My pleasure. Thank you so much for having me.

Useful Links:

Wenceslaus Hollar Map of London

Other Medieval London podcast episodes:

Episode 64 – Medieval Toilets in London

Episode 61 – Medieval London at the Museum of London

Episode 48 – Leper House in London

Episode 41 – Medieval Friaries

Episode 38 – The Black Death: London’s First Plague