Welcome to the London History Podcast. I am Hazel Baker from London Guided Walk co uk. Step back in time with us as we journey into the heart of London’s seven dials in the 1920s and 1930s, a neighborhood unlike any other, bursting with color, diversity and drama. In this episode, we uncover the untold stories and simmering tensions that define seven dials as it became a crossroads for migrant communities, working class families, and bohemian nightlife Here, vibrant cafes, rubbed shoulders with jazz clubs and market stalls while the specter of urban improvement , threatened to reshape everything familiar.

London Guided Walks » Episode 148: Seven Dials in the interwar Years

Episode 148: Seven Dials in the interwar Years

She has won awards for tour guiding and is proud to be involved with some great organisations. She is a freeman of the Worshipful Company of Marketors and am an honorary member of The Leaders Council.

Channel 5’s Walking Wartime Britain(Episode 3) and Yesterday Channel’s The Architecture the Railways Built (Series 3, Episode 7). Het Rampjaar 1672, Afl. 2: Vijand Engeland and Arte.fr Invitation au Voyage, À Chelsea, une femme qui trompe énormément.

Professor Matt Houlbrook is a leading authority in cultural history and Professor of Cultural History at the University of Birmingham. His research focuses on the social and cultural life of modern Britain, with particular interest in the everyday experiences that shaped London in the early twentieth century.

In this episode, we explore his latest book, Songs of Seven Dials: An Intimate History of 1920s and 1930s London. Drawing on rich archival research, Matt uncovers the overlooked history of Seven Dials through the lives of its residents and the turbulent events that shaped the area. He examines questions of race, class, and identity, revealing how this distinctive corner of London contributed to the making of the modern city. When not researching and writing, Matt continues to explore the cultural histories that bring London’s past vividly to life.

Welcome to the London History Podcast. I am Hazel Baker from London Guided Walk co uk. Step back in time with us as we journey into the heart of London’s seven dials in the 1920s and 1930s, a neighborhood unlike any other, bursting with color, diversity and drama. In this episode, we uncover the untold stories and simmering tensions that define seven dials as it became a crossroads for migrant communities, working class families, and bohemian nightlife Here, vibrant cafes, rubbed shoulders with jazz clubs and market stalls while the specter of urban improvement , threatened to reshape everything familiar.

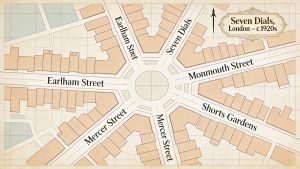

1920s map of Seven Dials

I am thrilled to be joined by Professor Matt Houlbrook, a leading authority in cultural history and professor at University of Birmingham. Today we’re here to dive into his latest work, songs of Seven Dials, an Intimate History of 1920s and 1930s London.

Drawing on vibrant archival research, the book explores the untold history of seven dials through the lens of remarkable residents and the turbulent events that shape their lives, professor Holbrook guides us through the struggles over race, class identity, and the contested making of modern London.

Transcript:

Hazel: Welcome Matt.

Matt: Oh, thank you very much for having me. It’s a pleasure to be here.

Hazel: And this is one of the eras that we don’t very often cover in the London History Podcast, mainly because I think it’s one of those eras that we don’t really consider history. It was a hundred years ago, but it still doesn’t feel mentally that long.

Matt: Yeah, I think that’s really interesting. Perhaps it feels very familiar. A lot of the things, a lot of the things that we take for granted today from Britain state to the mass democracy through to different kinds of nightlife and mass culture came into being in the 1920s and the 1930s. And when we look at pictures, color pictures, moving pictures even of the period, it all just looks, looks closer than perhaps it is.

1920s flapper girl

In lots of ways. That’s what got me interested in the period. I think it has been overlooked, by historians, by popular histories until very recently misunderstood as well if it hasn’t been overlooked. And I think so it’s one of the things that I’m trying to, one of the things that I’ve tried to do in my career in this book is just another example of that to try and think about how. Try and think about how so much of what we take for granted about Modern [00:03:00] Britain actually came into being in the twenties and thirties, that if it looks familiar, it doesn’t really seem a hundred years ago. That’s because it’s the moment in which our world started to come into being and be recognizably modern in many ways.

Hazel: What drew you in particular to the area of seven dials?

Matt: There are different ways that, to answer that question, I think the book Songs of Seven Dials is about it takes as its starting point a libel trial which Sierra Leonean cafe owner called Jim Kitten and his wife Emily Kitten, who’s born in the very, very poor neighborhood in the east end of London, do a pleasant right wing newspaper called John Bull for libel the. Newspapers published a series of really horrible racist articles about their cafe in the 1920s. I think what struck me is, on the one hand, it’s really, the presence of a couple, like Jim and Emily can in a place like Seven Dials. It’s completely normal. It’s ordinary in the 19 and the 1930s, but there’s an extraordinary part to the story, which is that. Which is that they do take that kind of unusual step of suing a national newspaper for libel and then case, cafe questions in the House of the Parliament, questions to the home secretary. William Joynson-Hicks about the regulation of London’s nightlife, but also crucially about whether or not there is a kind of a color bar at work in Britain and the British Empire. I suppose I came to seven dials from a roundabout route. to understand the cafe. To understand how something mundane ended up becoming so remarkable. And it turned out after kinda many years working and thinking about the case. It turned out that understanding the libel trial. And understanding why this cafe and not others generated questions in parliament actually takes you to a very local history about urban improvement, about gentrification, about the clash between rich and poor and this sort of battle to define what modern London will be.

Hazel: How did seven dials differ from other parts of London at the time? Then in terms of diversity and community spirit?

Matt: Seven tales is really interesting. It’s. One of the running jokes amongst authors of various sorts, Agatha Christie and people like that in the twenties, is that no one really knows where seven dials is. They often think that there’s a kind of a line in Agatha Christie’s novel, the Seven Dials Mystery, where a character just assumes or thinks that seven dials in the East end.

And I think that’s revealing the seven Dials clearly. Today in the heart, the West End Sandwich between Covent Garden and Soho and Bloom three. But in many ways, in the 1920s and the 1930s, its population, its kind of character is much more like or somewhere like that. It’s mostly working class. Its population is exceptionally diverse. It has residents and small business owners from across Britain and Ireland, France or Belgium or Eastern Europe, across the British Empire. It’s a place of small workshops, shops, and eating houses and cafes, and actually quite big factories making metal. In the context of London as a whole, it’s not necessarily that distinctive. What makes it stand out and what in many ways makes it, I think, feel and appear like an island in the middle of the west end is that all of these things are taking place so close to the centre of mass culture and consumerism in London. And that I think is what makes it [00:07:00] quite distinctive. Crime writers often talk about. Often talk about how they can pace the change in the air as they cross into seven dials precincts. And that’s poetic license of course. And people and goods and objects move in and out of seven dials all the time. think does, it does hint a bigger truth that. By the time of the 1910s and the 1920s, seven dials is, it’s almost the kind of an island in the heart of the stand. It’s a place like backstage to the front stage of theatreland. It’s the place where the porters who work at Covent Garden Market live rather than work. I think that’s what makes it interesting.

Hazel: Now you mentioned this libel trial in 1927 with the cafe owner. Why was it such a turning point? For the neighborhood.

Matt: Yeah. I don’t think it’s a turning point in a good [00:08:00] way. a, but I think the best way of thinking about the libel trial is a moment at which a lot of conflicts, simmering conflicts and bubbles over and come to a head. So seven dials. At the start, at the end of the First World War seven dials were poor. It’s working class and it’s declining. So it’s an area which still carries the legacies of its reputation as a Victorian slum at the same time, in that kind of giddy period after the first World War. The West End is expanding so property developers, theatrical entrepreneurs are looking for places to build new theaters, new office blocks, and new department stores. And at the same time, also, Covent Garden Market had run out of space. And so Market Traders looking for warehousing and wholesale space, and they start to look north at seven dials. So what begins to [00:09:00] happen? And I think the conflict around Jim and Emily Kitten’s Cafe is as property developers and politicians start to get big ideas about what seven dials might become, property is cheap. It’s close to the West end, it’s close to Covent Garden, and so it just looks like a really good opportunity to develop this working class area. In ways that would transform it into a kind of plaza to rival Piccadilly Circus, for example. So that’s the kind of, I think the underlying conflict, the sort of desire of property developers and politicians to turn a place of work and home into a kind of space of upscale consumerism or office work. I think. What happens in the libel trial is that these kinds of tensions become bound up with some particular local conflicts within the neighborhood.

[00:10:00] and the series of articles published by the newspaper John Bull are really part of a bigger campaign to push working class communities, particularly black working class communities out of seven dials. And I think one way of reading the libel trial, partly Jim and Emily Kitten are trying to protect their reputation and their business. That the articles in John Bull just destroyed their takings over the course of 1926. But they’re also, in many ways, trying to stand up for or to protect a really important black and Asian social hub in the heart of Central London.

Hazel: So how did issues of race, and you mentioned the color bar shape Everyday life in seven dials during this period?

Matt: It is a really good question. I think there are two different ways of answering that question about the color bar. One is that when Jim and Emily Kitten set up the cafe and [00:11:00] begin to cater for a clientele, a really diverse clientele that includes loads of people who live and work in Seven Arts itself, but also black and Asian sailors or students or jazz students from across London. Doing is trying to create a sort of social space in the context of a commercial nightlife where it is increasingly difficult for black agents. There’s a kind of moment during the First World War where we fought the war. Summons up kind of the people and the resources of the Empire, and many thousands of Black and Asian people respond to that corps serving in the Merchant Navy, for example. But there’s also then a really virulent post-war reaction, a racist reaction against the black and Asian presence in Britain. Most obvious examples of that are the kind of the violent race riots, what are called race riots in [00:12:00] 1919, which take place in port towns and cities across Britain, normally started by sailors normally to do with sort of competition over jobs in the shipping industry. But in the aftermath of those riots, they’re the growing effort by the government and also a whole range of media entrepreneurs too. To black and Asian Britons as somehow alien or unwanted or other an alien presence in a land where they don’t belong. Now, that’s not true that black and Asian Britain’s citizens of the empire have the right to live and work in Britain, there’s a growing effort in the 1920s to push them out, to exclude them from Britain, both legally and also through the kind of newspaper articles that sort of really virilant Newspaper rhetoric that you see in the newspaper, John Bolt. So I think the cafe in a way is a, kind of commercial cultural response to [00:13:00] political change and legislative change in a period when it’s increasingly difficult for black and Asian Britons to find, somewhere to socialize, to gather, to stay, or to drink or to eat. This is a kind of home from home and it’s quite clear from. It’s quite clear from reading the testimony of the cafe’s customers, that’s how they experience it. There’s nowhere else that will let them relax in quite the same way, and that’s why it has become so popular. But the cafe itself is a response to the bar. At the same time, I think the way that the cafe is treated very quickly becomes the focus of quite intrusive patrolling from police officers based at Bo Street Police Station a few minutes away. It attracts the hostile attention of newspapers like John Ball, who see it as a den of Vice and iniquity that should be removed from the heart of London. So the focus on the cafe is a [00:14:00] problem as a center of crime and vice. Reflects the kind of wider rhetoric, the wider moral panic around race and nationality in Britain in the 1920s.

Hazel: Continuing on from, you were saying about the cafe creating a cultural hub. How did the club’s, cafes, or the nightlife influence the culture and reputation of seven dials?

Matt: Yeah, Seven Dials. In the context of Seven DIals, the cafe, it’s one of the few venues that run by a black business owner, but it sits alongside cafes, restaurants, eating houses, butchers, and other shops run by Eastern European Jewish migrants by recent migrants from across Italy. Increasingly from people who have left Greece and Cyprus in the 1930s. So it’s a neighborhood cafe. These are all neighborhood eating places. They never really make it into the pages of urban [00:15:00] guidebooks or ecker. You don’t get restaurant critics, even intrepid, urban slummers going to the cafes and eating houses of Seven Dials in the way that they do to Soho. But these are all places that cater for their local community. that people from the Italian community come to gather and exchange news and gossip with their compatriots, be they black or Asian sailors and students passing through Britain, coming for Jim and Emily kittens, rice and curry, and afternoon tea. This is just, this is part of the hustle and bustle of everyday life in a cosmopolitan working class area. They do have an effect on how the neighborhood is understood. I think the important thing about seven dials in the twenties and thirties that the way that people talk about it and think about it from newspaper proprietors, journalists to police and politicians, defined by. Seven Dials’s history as a Victorian slum, one of the poorest parts of London, [00:16:00] associated with crime and vice and poverty and depravity from the 18th century through the end of the 19th century. Now, seven dials isn’t quite like that by the 1910s, the 1920s, it’s becoming increasingly respectable, even at the same time as all of the buildings begin to decay and fall apart. But the way that people look at it is still shaped by this, the idea that it’s somehow a dark spot at the center of London, and that’s really important. I think what the raids on the Kittens Cafe do and what the raids on clubs run by Russian or Italian entrepreneurs do is. Slowly reinforce this sense that Seven Dials is a dodgy, disreputable neighborhood on the edges of the West End. time there’s a raid on a nightclub on Grayson Andrew [00:17:00] Street, time there’s a prosecution that relates to somebody, one of Jim and Emily Kitten’s customers, it’s reported in the news and the kind of the effect of these. drip, drip of newspaper reporting is to cement a particular image of Seven Dials as a problem that needs to be fixed, and in lots of ways that reporting and the prosecution of the nightlife sort of, it plays into the hands of property developers and politicians. They see an opportunity in Seven dials, an opportunity for gentrification, opportunity for to make money in seven dials. The more that it’s defined as a problem by newspaper reporting and court cases the stronger the case they can make for either redeveloping the whole area or demolishing the whole thing and rebuilding it from scratch.

Hazel: When you about that drip. The history of Seven Dials and how it reveals about what it reveals about the early forms of gentrification in London. Everything seemed to be pointing in one [00:18:00] particular direction. By 1910, it was tidying itself up. Communities were being created, and yet there’s a big clash now from existing and then this gentrification that’s going to be forced upon them by eradicating certain problems.

Matt: The big moment. I think one of the defining moments is around 1919, 19 20. Politicians and planners from Holburn for council put forward these grand plans to demolish seven dials and build it again. the idea is. That outta this sort of tangle of courts and yards and streets, it will create a grand plaza that will rival Picadilly circus and there’ll be five dials.

There will be these big, thoroughfares where cars can speed through. There will be these monumental island blocks where there will be offices and department stores. That seven dials will become what Kingsway became a [00:19:00] decade or So And these are, these plans are launched a great fanfare in 1920. Now, of course, they come to nothing. They quickly run up against the problem that there’s very little money local government in London at the start of the 1920s, there’s not enough funding to make the plans happen. They get bogged down in the sort of the lanine conflicts between the London County Council, Borough Council to the South and Holborn. And then they fizzle away. But there’s a period between 1920 and in the late 1920s when everyone just assumes that Seven Dials is gonna be demolished and go completely. And I think that’s the really important context for. What happens around the cafe? That’s the sort of signal for theatrical entrepreneurs or property developers or hotel owners to to look at Seven Dials as a place where they can make money, that they know it’s gonna be redeveloped.

There are these grand plans to do something with it. [00:20:00] So that. It’s a place where it makes sense for them to invest. you can see that playing out for a period of several years when agents adverts, every time they advertise one of the corner blocks on the Seven Dials itself for sale, will talk quite explicitly about how this is a big development opportunity, particularly because of the grand plans for changing the area. When those are, those plans collapse by the late 1920s and Holborne Council becomes more interested in Bloomsbury, the area around the founding hospital as a kind of a site for preservation and redevelopment. I think what happens is Seven Dials is quietly forgotten. There’s no sense, no vision for what it should be, should it just become a problem to manage through public health intervention by looking at the state of the buildings by police and so on. And so it just continues to decline gradually the way through to the 1960s and the 1970s where there’s another [00:21:00] grand plan to redevelop Covent Garden and Seven Dials Another moment when politicians want to demolish the whole area and start again. But at that point, a successful campaign to preserve this sort of historic quarter of Central London.

Hazel: So what were some of the biggest myths about seven Dials in popular imagination? And also how does your research challenge them?

Matt: When historians think about seven dials, they might think about two things either. That moment between its 17th Century Foundation and the late 19th century where a grand plan development turns into a notorious slum, or they might skip forward to the period since the 1970s Activists, preservationists local communities fought a successful campaign to preserve seven dials from the attention of the Greater London Council. [00:22:00] And then Seven Dials became the kind of gentrified upscale consumerist paradise that it is today. And what I wanted to do, I guess in the book, was to look at the bit in between. Those two moments and think about what’s going on in seven Dials in the 1920s and the 1930s, because it’s not really something that’s a part of the popular history of area. But I think if we start to look closely at seven dials in the twenties and thirties, it gives us a way of understanding changes that are taking place across London in this period.

And I think that was the main thing. For me, writing this book about seven dials, not So much the challenge myths about the area itself, but to challenge some of the pervasive myths still govern how we think about the 1920s and thirties and their place in modern British history.[00:23:00]

Hazel: So how did the local and national newspapers shape the perception of Seven Dials? Both within London and beyond, because I know whenever I look at history I always jump onto what the newspapers were saying, but that doesn’t necessarily give me an overall viewpoint.

Matt: Yeah, if you look at newspaper reports of seven dials in the period that I’ve looked at. You would very much get the sense that it was a declining slum. a lot of reports of court cases, some attention to the grand plans to redevelop the era in the early 1920s, but they’re not very much actually after that.

I suppose one of the interesting things I talked about before was how often seven dials disappeared from view in the 1920s and 1930s. And that happens in newspapers too, to quite a striking degree. It’s often the kind of shorthand labels that people used to, that journalists used to describe it.

They often treat it as part of soho, part of [00:24:00] Covent Garden as sort of part of the fringes of Bloomsbury. And I think. I, one of the things that I wanted to do in the book is to show how a very distinctive area that it seeps into all of these better known neighborhoods around it. There’s something very distinctive about seven dials in terms of its population, in terms of the balance between residential community and the kind of the businesses, the manufacturing business that are taking place there. And also it’s cosmopolitanism. Think that isn’t necessarily something you get a sense of from reading contemporary newspapers.

Hazel: Are there any personal stories or characters from your research that really particularly struck you or stayed with you?

Matt: Yeah. There’s one place actually, the people who inhabit it. stick with me so the place is a [00:25:00] small tenement at five lumber court, which is just tucked away behind the main streets in seven dials and lumber court is probably one of the poorest. of seven dials from the 19th century onwards when Charles Booth’s social investigators passed through there in the 1890s. They’re struck by the presence of what they describe as prostitutes and bullies and thieves, and it’s poor. It’s rundown and it’s a sort of tiny alleyway in lots of ways. And I think in the book I’ve got, I got really interested in, like I said, number five, number lumber court. In the 1920s, it’s rented by a woman called Nelly Rigianni who’s born in South London then married, and then remarried. a Victor Reginalli, who’s from the Italian speaking part of Switzerland, and they lived together in this house for maybe [00:26:00] perhaps two decades. And in the 1921 census, which Nelly Ani completes the return, it’s clear that she’s running this as a boarding house and it’s a boarding house where almost all of the people living there on the sort of three or four floors are young women. They’re young women who have either to seven dials from suburban London or Ireland or the north of England and beyond, and they’ve come. the kind of low paying service industry or manufacturing jobs that sort of. They keep London going. They actually, in many ways, make the mass culture of the 1920s. So there are a couple of young women who work in the Lambert and Butler cigarette factory just to the southeast of seven dials. the dancing structures, Connie Ato in our early twenties who works at Brett’s Dancing Club on Shaftsbury Avenue. There are milliners And seamstresses and all of these kinds of jobs [00:27:00] the unseen work of the 1920s is in this house at five lumber court. I think it’s really interesting because it gives us another way of thinking about the modern woman or the flapper of the 1920s when we think of this period. Our temptation is to think straight away of the kind of brittle glamor and hedonism of the scantily dressed jazzy flapper in her silk stockings, and short dresses and cloche hats and all the rest of it. And in Some ways you can find that version of the Modern Woman of the 1920s in Five LU Lumber Courts. 2018 is a nightclub hostess. She’s employed at one point in the venue, run by Mrs. Kate Merrick, one of the most famous nightclub hostess, nightclub owners of the 1920s. And the inspiration for the BBC. Yeah. Yeah. So the inspiration for the BBC TV show Dope Girls. So Conni 18, she fits with [00:28:00] that story, right? Her job is to look glamorous, to look glamorous, to teach men to dance, and to charm them out of their hard earned income. And there are others, her mother, some of her other friends who live there. The boarding houses in court are clearly part of that world as well. I think when you look at the census records, you get a sense of how the 1920s isn’t just about glamor and fashion and nightlife. about new economic opportunities for young working class women, new industries, and crucially, it’s about the story of the twenties, if you start from lumber court, it’s not about hedonism or glamour. It’s about expropriation and exploitation of young women’s labor, and I think that story is much more challenging in lots of ways. The two women who worked in Lamber and Butler [00:29:00] cigarette factory that I talked about, when the 1921 census was taken that June, they’re both out of work and they’re out of work because of the national economic slump that has rippled across mostly Northern England. And Wales and Scotland, but it’s also rippled across central London and leaves a huge number of men and women working in precarious roles in the service industry or manufacturing out of work in that time. So there’s a story there about hardship, a story about making ends meet and finding somewhere to live as an independent woman in a strange city. There’s also a story in five Lumber Court about the dangers or the tragedy of the nightlife of Central London. A year after the 1921 census is taken, one of Nelly Rigianii’s borders, a young woman called called Lillian May Davis is found dead in her room by her, by one of, by her roommate taking an overdose of cocaine. The story becomes one of these sort of moral panics, these core celebra about the dangers of seven dials, the dangers black men selling drugs to young white women of moral corruption and contagion. It’s a reminder, I think of the darker side of the nightlife of the 1920s. So I think that’s probably, that it’s that sort of example. It’s that really drove me into. It made me interested in number five lumber court. I think, I could talk about this for ages if you let me go on. I think the other interesting thing lumber court, about this address and about Nelly, is that she appears in the autobiography of a remarkable woman called Mabel Lethbridge, written in the 1930s. Mabel Lethbridge goes on to be a fairly well known writer. First female estate agent, but she’s also, she was born in 1900. In 19, at the end of the great War, she’s involved in a horrific accident explosion in [00:31:00] ammunitions factory leaves her that, that means that she loses the leg and a hearing and is in just excruciating pain and chronic pain for the rest of her life. In the early 1920s after this accident, Mabel Lethbridge finds her way to seven dials and finds her way at one point to Nelly Ian’s boarding house. So you can see from Lethbridge autobiography that she’s aware seven Dials reputation, that it’s supposed to be this sort of den of vice and iniquity and a terrible slum. But for her, the way that she experiences it is a kind of place of warmth, of community, kind of an authentic welcome that she doesn’t find anywhere else in her life in this period. So she’s got these amazing accounts of sitting in Nelly, Ian’s kitchen, looking out for the rate collector, but also [00:32:00] of just the kind of the welcome that she finds in Seven Dials in this period. I think that too, if you put these different things together, 1921 census this remarkable autobiographical account, you just really start to get a different sense of what seven was like, but also what the 1920s and 1930s were like.

Hazel: Fantastic. So listeners, if that has wetted your appetite to learn more about seven dials in the 1920s and thirties, then Matt Holbrook’s book. ’cause songs of Seven Dials, an intimate history of 1920s and 1930s. London is out now. Thank you very much, Matt. It’s been brilliant.

Matt Houlbrook’s book – Songs of Seven Dials

Matt: Thank you for having me.