Join London tour guide Hazel Baker as we uncover the secrets of the Iron Duke the Duke of Wellington. Discover his ingenious survival tactics, fascinating gadgets, and the surprising story behind the famous Wellington boot.

London Guided Walks » Episode 140: The Iron Duke: Gadgets, Survival & Innovation

Episode 140: The Iron Duke: Gadgets, Survival & Innovation

Host: Hazel Baker

Hazel is an active Londoner, a keen theatre-goer and qualified CIGA London tour guide.

She has won awards for tour guiding and is proud to be involved with some great organisations. She is a freeman of the Worshipful Company of Marketors and am an honorary member of The Leaders Council.

Channel 5’s Walking Wartime Britain(Episode 3) and Yesterday Channel’s The Architecture the Railways Built (Series 3, Episode 7). Het Rampjaar 1672, Afl. 2: Vijand Engeland and Arte.fr Invitation au Voyage, À Chelsea, une femme qui trompe énormément.

Related Podcast Episodes:

Episode 37: Bridgerton and Regency London

Recommended Reading:

Duke of Wellington, the Iron Duke: Key Accomplishments

Battle of Waterloo

5 Iconic Quotes by the Duke of Wellington

Transcript:

Hello and welcome to another episode of London History Podcast. I’m your host, Hazel Baker Historian, tour guide and CEO of londonguidedwalks.co.uk. Today we’re venturing beyond the typical tales of battles and politics to explore a rather extraordinary side of one of Britain’s most celebrated military heroes. When we think of Arthur Wellesley, the Duke of Wellington, we picture the Iron Duke commanding at Waterloo, defeating Napoleon, or perhaps striding through the corridors of power as Prime Minister. But what if I told you he had a walking stick with a deadly secret; a concealed sword?

Wellington’s sword stick wasn’t just some Victorian oddity. It was part of a fascinating collection of practical innovations and cutting-edge gadgets that reveal a man far ahead of his time. From revolutionary footwear to battlefield telescopes, from pioneering hearing aids to military communications systems, Wellington embraced technology in ways that would surprise those who knew him only as a military commander.

To begin, let’s understand the remarkable man himself and the turbulent world that shaped him into both Britain’s greatest general and one of history’s most practical innovators.

THE MAKING OF AN IRON DUKE – WELLINGTON’S ORIGINS AND EARLY STRUGGLES

Arthur Wesley (he wouldn’t become Wellesley until 1798) was born into the Protestant Ascendancy of Ireland on the 1st of May 1769, in Dublin. To understand Wellington’s later embrace of practical innovation, we need to grasp what this background meant. The Protestant Ascendancy was a small Anglican ruling class that dominated Ireland socially, economically, and politically from the 17th century onwards.

These were descendants of English and Anglo-Norman settlers who had received confiscated Irish Catholic lands from the Crown. By the late 18th century, this elite group of perhaps ten thousand families controlled virtually all of Ireland’s landed wealth and political power. Wellington’s father, Garrett Wesley, was the 1st Earl of Mornington, and the family epitomised this Anglo-Irish aristocracy.

But here’s the crucial detail that shaped Wellington’s character: the family was perpetually short of money. When his father died in 1781, leaving debts of over £20,000 (equivalent to about £2.5 million today) the financial crisis forced harsh choices. Young Arthur was withdrawn from Eton, where he is reportedly to have been involved in incidents such as a barring-out (student rebellion) , and sent to less expensive schools in Belgium and France.

His mother, Anne Hill, famously despaired: “I vow to God I don’t know what I shall do with my awkward son Arthur. He is food for powder and nothing more” which reflected her disappointment about Arthur’s perceived lack of academic success and social polish compared to his siblings, and her belief that he was destined for a military career where he might only serve as cannon fodder. This wasn’t mere maternal exasperation; but reflected the harsh realities facing younger sons of impoverished aristocratic families, think Colonel Fitzwilliam in Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice. The military was literally seen as the last resort for boys deemed unsuitable for more prestigious careers.[1]

This early experience of financial constraint would profoundly shape Wellington’s character. Unlike many aristocrats who lived in cushioned luxury, he learned from childhood that resources were limited and must be used efficiently. This practical mindset would later drive his innovations in everything from military equipment to personal gadgets.

The social context here is crucial. In 1787, when Wellington was commissioned as an ensign in the 73rd Regiment of Foot, the British Army operated on the purchase system. Wealthy families could literally buy their sons’ commissions and promotions. An ensign’s commission in infantry cost £450, probably equivalent to about £52,000 today. A lieutenant colonelcy cost £3,500 more to £400,000 in modern money.

But this wasn’t just about wealth; regimental colonels could refuse commissions to men they deemed socially unsuitable, preserving the officer class as an aristocratic preserve. Wellington’s family scraped together the money for his initial commission, but each subsequent promotion required fresh loans and financial juggling.

By 1793, when Wellington became Lieutenant-Colonel of the 33rd Foot, he had spent over £4,000 (nearly half a million pounds in today’s money) on his military career. This constant pressure to justify expenses through results would become a hallmark of his leadership style. He couldn’t afford failure, either financially or professionally.

THE REGENCY WORLD – BRITAIN IN UNPRECEDENTED TRANSFORMATION

To understand why Wellington would later carry a swordstick umbrella through London’s streets, we need to appreciate the extraordinary turbulence of the age he lived through. Wellington’s career spanned the Regency period (that fascinating era from 1811 to 1820 when the Prince of Wales ruled as Regent during his father George III’s madness) but also the broader transformation of British society from 1790 to 1850.

This was an age of sharp social contrasts that would challenge any leader’s ingenuity. The wealthy Regency elite lived lives of unprecedented luxury and refinement. They patronised the arts, built magnificent houses in the new neoclassical style, and created what we now call “Regency fashion.” But beneath this glittering surface lay desperate poverty and social unrest.

The Napoleonic Wars, which raged from 1803 to 1815, brought economic hardship, mass unemployment, and inflation that quadrupled food prices. The Industrial Revolution was simultaneously transforming Britain, creating immense wealth whilst generating urban slums where life expectancy could be as low as 22 years. In Manchester, the average working-class person died at 15; in Liverpool, at 17. An East End London labourer in the 19th century was approximately 19 years, while the overall London average around the mid-century stood at just 37 years.

Political power remained firmly in the hands of perhaps 300,000 property-owning men (less than 3% of the population). The Tory party, which dominated from 1783 to 1830, represented these landed interests. But revolutionary change was sweeping Europe. The French Revolution had executed a king, abolished aristocracy, and spread democratic ideas across the continent.

For Britain’s ruling class, this created an atmosphere of constant existential threat. The spectre of revolution haunted every political discussion. When food prices soared in 1819, the government’s response was the Peterloo Massacre, where cavalry charged a peaceful reform meeting in Manchester, killing eleven people and injuring over 400.

The statistics of violence are telling. Between 1811 and 1831, there were over 600 food riots across Britain. London experienced frequent bread and food riots, especially in years of bad harvest or war, spiking in 1800–01, throughout the 1810s, and again in the 1820s.

The Luddites destroyed textile machinery in coordinated attacks. The Swing Riots of 1830 saw agricultural labourers burn hayricks and destroy threshing machines across southern England. Captain Swing letters, threatening notes sent to farmers and magistrates, numbered in the thousands.

In 1820, a group of radical activists in London, led by Arthur Thistlewood, hatched an extraordinary plot now known as the Cato Street Conspiracy. Their goal was to assassinate the entire British cabinet, including Prime Minister Lord Liverpool, and decapitate the most hated figures, displaying their heads on spikes as grisly trophies to incite the London crowd to rise up

. On 23 February 1820, the police raided their meeting place in a hayloft on Cato Street, catching most of the plotters before they could act. Five were later hanged and publicly decapitated for treason,(the last public beheadings in Britain), while others were transported or imprisoned.

It was a small wonder, then, that political figures felt the need for personal protection. The line between legitimate political opposition and violent insurrection seemed perilously thin in a world where Prime Ministers could be shot dead in Parliament and kings could lose their heads to revolutionary mobs.

WELLINGTON’S MILITARY APPRENTICESHIP – INDIA, INNOVATION, AND THE ART OF COMMAND

Wellington’s transformation from awkward younger son to military genius began in India, where he served from 1796 to 1805. His elder brother Richard had been appointed Governor-General, providing Arthur with opportunities that would have been impossible otherwise. But Wellington seised these chances with characteristic determination and innovation.

The numbers alone tell the story of his Indian success. At the Battle of Assaye in 1803, which he later considered his finest victory, Wellington defeated a Maratha army of 50,000 with just 7,000 troops. His casualties were severe: 1,566 killed and wounded from his tiny force, a loss rate of over 22%. But the enemy suffered far worse: 6,000 casualties and the complete destruction of their army as an effective force.

India taught Wellington lessons that would prove crucial throughout his career. He discovered the value of secure supply lines, often marching with bullocks carrying sixty days’ provisions. Most importantly, he developed his gift for defensive warfare, choosing strong positions and forcing enemies to attack him on the ground of his choosing.

But India also revealed Wellington’s innovative approach to military technology. He was among the first British commanders to systematically use rockets (weapons derived from those used by Tipu Sultan against earlier British forces). He experimented with new forms of camp equipment, developing portable bridges and improved artillery carriages.

The statistics of Wellington’s Indian commands reveal his organisational genius. Between 1798 and 1805, he commanded forces totalling over 50,000 men across multiple campaigns. His logistics network required 120,000 bullocks, 30,000 camp followers, and supply depots stretching across hundreds of miles. Yet his forces never suffered a major supply failure or epidemic; remarkable in a theatre where disease typically killed far more soldiers than enemy action.

When Wellington returned to Britain in 1806, he brought with him prise money worth £42,000 which is about £4 million today. But more importantly, he returned with a reputation for competence and innovation that set him apart from other commanders. As he wrote to his brother: “I have acquired a local knowledge of the country, and of the enemy’s resources and mode of warfare, which may be valuable.”

THE PENINSULAR LABORATORY – WHERE WELLINGTON PERFECTED THE ART OF MODERN WARFARE

The Peninsular War from 1808 to 1814 became Wellington’s laboratory for military innovation. Here, leading British forces against Napoleon’s marshals in Spain and Portugal, Wellington developed the tactical brilliance and technological sophistication that would culminate at Waterloo.

The scale of Wellington’s Peninsular command was unprecedented for a British general. By 1813, he commanded over 100,000 troops across multiple nationalities: British, Portuguese, Spanish, and various German contingents. His intelligence network employed hundreds of agents, from Spanish guerrillas to French deserters. His supply system stretched from Lisbon to the Pyrenees, requiring coordination of ships, mules, ox-carts, and local contractors.

The casualties statistics from Wellington’s major Peninsular battles reveal both the intensity of the fighting and his growing tactical sophistication. At Talavera (1809), his first major victory, Wellington suffered 5,365 casualties from 20,000 engaged, a 27% loss rate that horrified him. By Salamanca (1812), he achieved decisive victory with only 3,200 casualties from 48,000 engaged, just 6.7% losses whilst inflicting over 14,000 casualties on the French.

More remarkably, Wellington never lost a major battle—the only commander in the Napoleonic Wars who could make that claim.

THE DANGEROUS STREETS OF LONDON – POLITICAL VIOLENCE IN THE AGE OF ASSASSINATION

This military fame, however, came with genuine dangers that extended far beyond the battlefield. Wellington returned to Britain in 1815 as the hero of Waterloo, but also as a target for political violence that was becoming increasingly common across Europe.

The assassination of Spencer Perceval on 11th May 1812 sent shockwaves through the British establishment.

Most disturbing for Wellington and other leaders, Bellingham had acted entirely alone—there was no conspiracy to uncover, no network to root out.

Wellington himself faced increasingly direct personal threats throughout his political career. His support for Catholic Emancipation in 1829 made him deeply unpopular with Protestant extremists. Angry crowds regularly gathered outside Apsley House, and on several occasions, windows were broken by stone-throwing mobs. The iron shutters Wellington installed (they’re still there today) gave the building its nickname of “The Iron Duke’s house.”

The most dramatic personal confrontation came in March 1829, when Wellington fought his duel with George Finch-Hatton, the 10th Earl of Winchilsea. The Earl had publicly accused Wellington of “an insidious design for the infringement of our liberties and the introduction of Popery into every department of the State.” Despite being Prime Minister, Wellington felt honour demanded satisfaction.

But before this peaceful conclusion, both men had loaded pistols and taken their positions twelve paces apart, fully prepared to kill or die over their political differences.

THE SWORD STICK – PRACTICAL SELF-DEFENCE IN A VIOLENT AGE

So when Wellington carried his sword stick through London’s streets, that concealed sword wasn’t paranoia; it was prudent preparation for documented realities. Contemporary accounts describe Wellington’s umbrella as being made of “oiled cloth and concealing a swordstick”—a dual-purpose design perfectly suited to England’s unpredictable weather and equally unpredictable political climate.

But Wellington’s armed umbrella was part of a much wider Victorian tradition of concealed street weapons that flourished among the upper classes. The purchase system that had brought officers their commissions also created a culture where gentlemen were expected to defend their honour personally. Duelling remained legal until 1844, and even after its formal prohibition, affairs of honour continued in modified forms.

Sword-sticks, umbrella-daggers, and similar implements were popular amongst the aristocracy and gentry who needed to maintain respectability whilst ensuring personal protection. These weapons were ingeniously designed to appear as ordinary walking accessories whilst concealing substantial steel blades that could be deployed instantly when circumstances demanded.

A well-made sword stick could fool even experienced eyes. The trigger mechanism was often concealed in the handle’s carving or metalwork, activated by twisting or pressing hidden catches. The blade itself was usually a substantial steel rod rather than a decorative toy—typically 18 to 24 inches long and sharpened to a lethal point.

Contemporary accounts reveal how sophisticated these weapons had become. The Art Journal of 1851 described sword stick as “marvels of mechanical ingenuity, combining utility with the most perfect concealment of their deadly purpose.” Many were made by the finest cutlers and featured high-quality steel blades that could penetrate clothing and cause fatal wounds.

The umbrella as a weapon had serious academic advocates who developed comprehensive fighting systems. Baron Charles Random de Berenger, writing in the 1830s, promoted umbrella self-defence in his influential books “Helps and Hints How to Protect Life and Property” and “Defensive Gymnastics.” He viewed the umbrella as invaluable for defence, capable of being “converted into a weapon” during emergencies or opened quickly to serve as a shield against multiple attackers.

THE WELLINGTON BOOT REVOLUTION – FASHIONING VICTORY THROUGH PRACTICAL INNOVATION

Of course, Wellington’s most enduring invention was the Wellington boot itself—an innovation that emerged from the same practical mindset that produced his sword stick umbrella. In the early 1800s, during the height of the Industrial Revolution when steam power was transforming British manufacturing and precision engineering was creating new possibilities, Wellington approached his shoemaker with characteristic attention to practical detail.

Mr George Hoby of St James’s Street, London, was perhaps the most prestigious bootmaker in Britain, serving royalty and the highest aristocracy. When Wellington commissioned his boot modification, this represented a significant investment—a pair of Hoby’s finest boots cost £8 to £12, equivalent to £800 to £1,200 today. For a man still struggling with debts from his military promotions, this was a serious financial commitment that had to deliver results.

The original Hessian boots worn by British Army officers were an inheritance from 18th-century European military fashion. These tall, soft boots made from calfskin reached about knee-high, decorated with tassels and featuring a small heel. They’d originally been worn by German mercenaries during the American War of Independence and had become standard dress for British cavalry and light infantry officers.

But Wellington identified specific problems with the existing design that hampered military effectiveness. The tassels caught on stirrups during mounted action. The high cut restricted leg movement during long marches. The soft leather provided insufficient weather protection during extended campaigns. Most critically for an officer who spent hours daily on horseback, the boots were uncomfortable during prolonged riding.

Wellington’s specifications to Hoby were precise: remove the tassels entirely, make the boots fit more closely around the leg to prevent chafing, cut them lower to allow greater freedom of movement, yet maintain sufficient height for protection against brambles and mud. The leather was to be treated with additional wax for increased weatherproofing, whilst the heel was to be reduced for better grip in stirrups.

The resulting Wellington boot represented a masterpiece of functional design. Fabricated in soft calfskin leather with low-cut heels and calf-high tops, they provided the perfect balance between protection, comfort, and appearance. The close fit prevented the boots from filling with mud during marches, whilst the weatherproofing kept feet dry during Spain’s notorious winter campaigns.

Wellington’s attention to practical details extended to the boot’s construction. He specified that the seams should be positioned to avoid pressure points during long rides. The leather thickness was carefully calculated—substantial enough for durability, but not so heavy as to cause fatigue. Even the boot-pulls were designed for rapid dressing, essential for an officer who might be called to action at any hour.

The timing of Wellington’s boot innovation coincided perfectly with his rising fame after Peninsular victories. When he triumphed at Vitoria in 1813, capturing King Joseph’s entire baggage train and effectively ending French control of Spain, Wellington became a European celebrity. His practical boot design spread rapidly through military and civilian society.

By 1815, after Wellington’s victory at Waterloo established him as the most famous soldier in Europe, the Wellington boot had become essential fashion among British gentlemen. Contemporary accounts describe how quickly the style spread. Captain Rees Howell Gronow noted in his memoirs: “Every fashionable man had his boots made in the Wellington pattern.”

The boot’s popularity reflected deeper social changes occurring during the Industrial Revolution. Precision manufacturing was making high-quality leather goods more widely available. Improved transport networks allowed London fashion to spread rapidly across Britain and throughout the Empire. Most significantly, Wellington’s heroic reputation gave his practical innovations enormous social cachet.

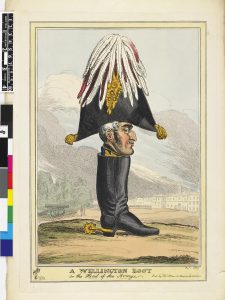

By the 1830s, political cartoonists were depicting Wellington simply as “a Wellington boot with a head,” so closely associated had he become with his footwear innovation. The satirical magazine Punch regularly featured caricatures showing the Duke as an animated boot, emphasising how completely his personal brand had merged with his practical invention.

Wellington himself remained ambivalent about this association. As he wryly observed when asked late in life what was the most inane remark he’d ever heard: “When someone said to me, ‘Do you know, Your Grace, that your name would be immortal, even if you had never fought a battle?’ I said, ‘How?’ And he replied, ‘Why, through the Wellington Boot!’”

The boots remained popular among the aristocracy throughout the 1840s, long before the rubber versions we know today. It wasn’t until Charles Goodyear’s vulcanisation process in 1839 and Hiram Hutchinson’s licensing arrangements in 1852 that the transition to waterproof rubber boots became commercially viable—part of the Second Industrial Revolution that transformed materials science and manufacturing.

OPTICAL EXCELLENCE – THE BATTLEFIELD TELESCOPE THAT CHANGED MILITARY HISTORY

Wellington’s technological innovations extended far beyond personal accessories into sophisticated military equipment that represented the cutting-edge science of his era. His telescope, made by Matthew Berge of London around 1802, became one of history’s most consequential military instruments—a device that may have changed the course of European civilisation.

This seven-draw telescope could magnify images 30 times, a remarkable achievement for early 19th-century optics. To appreciate its significance, consider the tactical challenges Wellington faced at Waterloo. The battlefield measured only 2.5 kilometres long by 1.3 kilometres wide, yet contained over 200,000 soldiers from three different armies. Without effective observation, commanding such forces would have been impossible.

The precision optics industry was experiencing revolutionary development during Wellington’s era. Companies like Jesse Ramsden and his successor Matthew Berge were pushing the boundaries of what 18th-century technology could achieve. Machine tools—themselves inventions of the Industrial Revolution—were making economical manufacture of precision metal parts possible for the first time in history.

Berge’s workshop at 199 Piccadilly represented the pinnacle of scientific instrument making. When he took over from Ramsden in 1800, he inherited techniques for grinding lenses and polishing mirrors that had been perfected over decades.

Wellington’s telescope provided unprecedented tactical awareness on the battlefield. At various distances, he could observe critical details that gave him decisive advantages over enemies who lacked such sophisticated equipment. At 300 metres, he could discern flag designs and thereby identify specific enemy units—crucial intelligence for assessing threats and opportunities.

At 450 metres, individual figures and uniform colours became visible, allowing Wellington to distinguish between different types of troops and assess their quality by their bearing and equipment.

At 600 metres, groupings of files (formations of troops) became clearly visible, enabling Wellington to understand enemy tactical deployments and anticipate their likely actions. The ability to observe enemy preparations before they were fully developed gave Wellington precious minutes to position his own forces advantageously.

At 800 metres, individual movement patterns suggested possible enemy intentions, allowing Wellington to predict attacks before they were launched. This early warning capability proved crucial at Waterloo, where Wellington repositioned his forces multiple times based on observations of French preparations.

At 1,200 metres, Wellington could assess artillery positions and judge troop quality by observing the smartness of their formations. Experienced units maintained precise alignments even at distance, whilst less reliable forces showed gaps and irregularities that revealed their weaknesses.

Contemporary accounts reveal how Wellington used his telescope throughout the Waterloo campaign. Captain Alexander Gordon, his aide-de-camp, recorded: “The Duke was constantly using his glass, scanning the enemy positions and our own lines. He seemed to see everything that was happening across the entire field.”

The telescope’s effectiveness was enhanced by Wellington’s systematic approach to battlefield intelligence. He positioned himself on high ground whenever possible, using church towers, hills, and even tall trees as observation posts. His staff carried detailed maps marked with distance calculations, allowing him to coordinate telescope observations with artillery ranges and troop movements.

As Wellington himself noted about the challenges of command: “All the business of war, and indeed all the business of life, is to endeavour to find out what you don’t know by what you do; that’s what I called ‘guessing what was at the other side of the hill’”. His telescope was an essential tool in this constant quest for battlefield intelligence that separated great commanders from merely competent ones.[3][2]

After Waterloo, Wellington’s telescope became a treasured historical artifact. The Duke presented it to Sir Robert Peel, the future Prime Minister, with an inscription reading: “Telescope by Berge of London used by the Duke of Wellington at the Battle of Waterloo, presented by the Duke to Sir Robert Peel.” This gift represented both personal friendship and recognition of the instrument’s historical significance.

The telescope now forms part of the Royal Armouries collection at the Tower of London, where Wellington later served as Constable for 26 years. It’s fascinating to think that this single optical instrument may have influenced the course of European history by giving Wellington the situational awareness he needed to coordinate the coalition that finally defeated Napoleon.

PERSONAL CHALLENGES – THE HEARING AIDS THAT REVEALED WELLINGTON’S CHARACTER

Even more ingenious was his hearing aid walking stick, which served the dual purpose of mobility aid and hearing enhancement—a perfect example of Wellington’s preference for multi-functional solutions. The stick contained a hollow chamber that acted as a resonating cavity, with a carefully designed mechanism that could be activated by twisting the handle to amplify conversations or other sounds.

These ivory and metal contraptions, whilst primitive by today’s standards, were the finest available to a man of Wellington’s stature and represented significant technological achievement. The craftsmanship was exquisite—the ivory components were carved by specialists who normally worked on scientific instruments, whilst the metal parts were made by precision engineers who created telescope components and chronometer mechanisms.

Wellington’s characteristic approach to problem-solving was evident here—practical, no-nonsense, and completely unashamed. As he once remarked about facing challenges: “Wise people learn when they can; fools learn when they must”.[3][2]

Contemporary accounts reveal how Wellington’s hearing loss affected his daily routine and social interactions. Mrs. Harriet Arbuthnot, a close friend who kept detailed diaries of her conversations with the Duke, noted: “His Grace has become considerably deaf since his accident, but he bears it with remarkable patience.”

Wellington’s hearing loss also affected his famous wit and conversation style. Friends noticed he became more sharp-tongued in social situations, possibly because he was straining to hear and became impatient with unclear speech.

Contemporary visitors often remarked on this combination of magnificence and practicality. The social reformer Frances Wright noted after dining at Apsley House: “The Duke lives surrounded by the trophies of victory, yet his conversation turns constantly to practical matters—improvements in agriculture, innovations in manufacturing, developments in science. He seems more interested in the future than in past glories.”

THE SCIENTIFIC DUKE – WELLINGTON’S PATRONAGE OF INNOVATION AND DISCOVERY

Wellington’s embrace of innovation extended far beyond personal gadgets into systematic patronage of scientific and technological development that helped shape the early Victorian era. His position as Master-General of the Ordnance in the 1820s placed him at the center of military technological development, whilst his social prominence made him a natural patron for inventors and researchers seeking support.

The scope of Wellington’s scientific correspondence, preserved in the Southampton University archives, reveals remarkable breadth of interest. His papers include correspondence with Charles Babbage about his calculating machine—an early mechanical computer that anticipated modern programmable devices. Wellington also received detailed reports about discoveries in magnetic compass variation and proposals for new medical apparatus to treat everything from headaches to rheumatism.

As Master-General of the Ordnance, Wellington described his department as being “specially charged with all military equipments, machines, inventions thereof and their improvement.” This wasn’t merely administrative oversight—Wellington took active interest in technological development and personally tested new weapons and equipment systems.

His correspondence with Colonel Henry Shrapnel, inventor of the explosive artillery shell that bears his name, reveals Wellington’s detailed understanding of ballistics and metallurgy. Wellington personally supervised trials of shrapnel shells at Woolwich Arsenal, analyzing their effectiveness against different targets and suggesting improvements to the design.

Similarly, his extensive correspondence with Sir William Congreve about rocket development shows Wellington’s appreciation for innovative weapons systems. In a letter of August 1822, Congreve wrote: “Under Your Grace’s patronage and protection, I feel confident of giving complete perfection to the rocket system in a very short time and making it not only the most powerful but also the most economical weapon that can be used.”

THE BROADER CONTEXT – WELLINGTON IN THE AGE OF TRANSFORMATION

Wellington’s career spanned from 1787 to 1852 (from the pre-industrial world of his youth to the high Victorian era of his death) making him perhaps the best-positioned observer of the most rapid period of change in human history to that point.

THE IRON DUKE’S FINAL CHAPTER – DEATH, LEGACY, AND LASTING INNOVATION

The timing of Wellington’s death marked the end of an era in more ways than one. The Great Exhibition of 1851 had showcased Britain’s industrial supremacy to the world, displaying technological innovations that would have seemed miraculous to the young ensign who had received his first commission 65 years earlier. The Crystal Palace itself represented the pinnacle of Victorian engineering (a building that embodied the same principles of practical innovation and systematic problem-solving that had characterised Wellington’s entire career.

Wellington’s various innovations from his revolutionary boot design to his practical sword stick, from his battlefield telescope to his pioneering hearing aids; remained influential long after his death. His boots evolved into the rubber Wellington boots that became essential equipment for farmers, gardeners, and outdoor workers throughout the British Empire and beyond.

The sword stick umbrella, whilst losing its martial applications as Victorian society became more peaceful, established a tradition of multi-functional personal accessories that continues today. Modern travelers carry umbrellas that serve as walking sticks, whilst outdoor enthusiasts use equipment that combines multiple functions in single devices; direct descendants of Wellington’s practical approach to personal gear.

His telescope contributed to the development of military optics that would transform 19th and 20th-century warfare. The precision manufacturing techniques developed for Wellington’s era of scientific instruments laid the groundwork for modern optical systems, from camera lenses to microscopes to the complex optical devices used in contemporary technology.

Perhaps most significantly, Wellington’s hearing aids helped establish acceptance of assistive technology among the upper classes. His open use of mechanical aids to overcome physical limitations demonstrated that technological solutions could enhance rather than diminish personal dignity.

But perhaps the most fitting tribute to Wellington’s legacy isn’t found in monuments or memorials, but in the everyday objects that still bear his name. Every time we pull on Wellington boots to face British weather, we’re using technology he pioneered. Every time we open an umbrella (even if it doesn’t conceal a dagger) we’re following in the footsteps of a man who understood that practical preparation could be the difference between success and failure.

That’s all for today’s episode of the London History Podcast. I hope you’ve enjoyed discovering the innovative and practical side of the Duke of Wellington; the man behind the legend who understood that true greatness often lies in the details of daily life and the systematic application of good ideas to real problems.

I’m Hazel Baker from London Guided Walks, and thank you for joining me in exploring London’s hidden histories. Keep discovering, keep questioning, and remember—sometimes the most fascinating stories are hiding in plain sight, just waiting for someone curious enough to look beyond the obvious. Until next time!

Thomas Lawrence, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Wellington Boot Punch BM 63059001

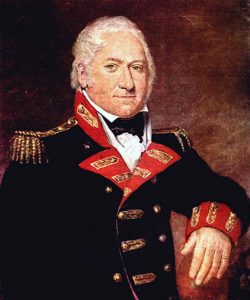

Unidentified painter, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons