Explore the history and former residents of Downing Street. In this episode, we uncover the stories and events that shaped the nation from this iconic street.

London Guided Walks » Episode 139: Downing Street – A Microcosm of London

Episode 139: Downing Street – A Microcosm of London

Host: Hazel Baker

Hazel is an active Londoner, a keen theatre-goer and qualified CIGA London tour guide.

She has won awards for tour guiding and is proud to be involved with some great organisations. She is a freeman of the Worshipful Company of Marketors and am an honorary member of The Leaders Council.

Channel 5’s Walking Wartime Britain(Episode 3) and Yesterday Channel’s The Architecture the Railways Built (Series 3, Episode 7). Het Rampjaar 1672, Afl. 2: Vijand Engeland and Arte.fr Invitation au Voyage, À Chelsea, une femme qui trompe énormément.

Related Podcast Episodes:

Episode 78: Georgian Landlords

Episode 79: Georgian Land Ladies,

Recommended Reading:

No. 10: The Geography of Power at Downing Street by Jack Brown (2024)

10 Downing Street: The Illustrated History by Anthony Seldon (1999)

Lodgers, Landlords, and Landladies in Georgian London by Gillian Williamson (2021)

Behind Closed Doors: At Home in Georgian England by Amanda Vickery

Boswell’s London Journal, 1762-1763

London 6: Westminster (Pevsner Architectural Guides)

Georgian London: Into the Streets by Lucy Inglis

Love and Marriage in the Age of Jane Austen by Rory Muir

Life in the Georgian City by Dan Cruickshank

Transcript:

Hazel Baker:

Welcome to the London History Podcast. I am Hazel Baker, and today we are strolling down one of London’s most recognisable streets—Downing Street. But there is far more to it than the famous black door and the prime ministers who have stepped through it. We will be uncovering the street’s full length and history—its grand houses, colourful residents, and the unexpected twists that have shaped this small but storied corner of Westminster.

This is a street where aristocratic balls and government memos once collided, where shoddy building work sat cheek-by-jowl with courtly ambition, and where you could find a Venetian radical living two doors down from a civil servant’s spinster sister.

We will explore not only its architecture—thin walls, fake mortar lines, and all—but also the extraordinary range of people who have called it home. Forget the political headlines for a moment: Downing Street has always been a place of layered lives and surprising stories.

I. Boggy Beginnings and a Master Survivor

The story of Downing Street begins, fittingly, with its namesake — a man who could survive any political storm and come out richer on the other side. Sir George Downing was born in Dublin in 1623

His childhood was spent across the Atlantic in the Puritan colony of Massachusetts. He was among the first handful of graduates from the fledgling Harvard College, destined — or so it seemed — for a life in the ministry.

But history had other plans.

On returning to England, Downing traded the pulpit for the sword. In the chaos of the Civil War, he rose to become Oliver Cromwell’s chief intelligence officer — effectively England’s spymaster. It was dangerous, shadowy work: intercepting messages, turning agents, and mapping the political loyalties of an unstable nation.

And then came the twist. With the Protectorate finished and the monarchy restored, George Downing made a calculation. He switched sides, pledged himself to Charles II, and — most damningly in the eyes of his former comrades — betrayed regicides who had once been his allies. Opportunistic? Certainly. Effective? Without a doubt. His reward was a knighthood, lucrative government posts, and the means to amass significant land holdings.

By 1682, Downing had purchased a prime stretch on the west fringe of Whitehall Palace land ripe for redevelopment. It was still, at that time, little more than marsh and market garden, but Downing saw its potential. On this soggy ground, he would stamp his name in London’s geography.

II. Before the Street: Monks, Breweries, and Gunpowder

Before the name “Downing” meant anything in Westminster, the plot had centuries of history baked into it.

In medieval times, the site was home to the Axe Brewery, owned by the Abbey of Abingdon, supplying ale to the area around the royal palace.

By the late 1500s, Elizabeth I had granted the land to one of her trusted courtiers, Sir Thomas Knyvet. He was a man whose place in history is sealed for a single night’s work. On 5 November 1605, it was Knyvet who seized Guy Fawkes beneath the Palace of Westminster and unearthed the Gunpowder Plot before it could devastate the king and Parliament.

Knyvet built himself a substantial house here, later known as Hampden House. His descendants lived with the royal palace almost in their front yard. Imagine the view from their windows in January 1649: across to Whitehall Palace, where a scaffold had been erected for the execution of Charles I. One of the most traumatic moments in English history, playing out like a theatre in the open air for anyone who cared to watch.

Long before George Downing began sketching terraces, this patch of ground had already witnessed monks, brewing, royal patronage, and revolution.

III. Shoddy Splendour: How the Street Was Built

When Downing finally set his redevelopment in motion, his aim was simple: create homes “for persons of quality” — but without paying for actual quality. He is said to have engaged the great Sir Christopher Wren, though historians debate how much Wren really had to do with the plans. What is certain is that Downing overruled the craftsmen whenever costs could be spared.

The houses went up with shallow foundations, walls so thin that some were actually hollow, and facades where neat mortar joints were simply painted on. From a distance, they looked like all the other new Georgian residences springing up in London. Up close, the illusion started to crack. Samuel Pepys had pegged Downing years earlier as “a perfidious rogue”, and more than two centuries later Winston Churchill would sigh that Number 10 was “shaky and lightly built by the profiteering contractor whose name it bears.”

And Number 10 itself? It isn’t a single house at all. It’s a hybrid — Downing’s modest terrace house at the front, stitched to a much larger, older mansion at the rear, creating a maze of rooms and corridors. Newcomers to the building still get lost in its eccentric layout, the product of expediency over elegance.

IV. Residents Beyond the Prime Ministers

In its early decades, Downing Street was a surprisingly eclectic address.

George Villiers, 2nd Duke of Buckingham

When it comes to Downing Street’s earliest—and most flamboyant—residents, few rival George Villiers, 2nd Duke of Buckingham. In the late 17th century, Buckingham wasn’t just a visitor here; he set up residence in the grand mansion that would eventually become part of Number 10.

Fresh from a life packed with duels, courtly intrigue, and political scheming, Buckingham made Downing Street one of the liveliest addresses in Restoration London. His home served as both a salon for wit and a headquarters for intrigue. It was here that Buckingham, a fixture of Charles II’s notorious “Cabal” Ministry, entertained the great and the good—poets, actors, ministers—amid lavish dinners and late-night debates. Known for his quicksilver intelligence and prodigal lifestyle, Buckingham’s time at Downing Street reflected the street’s own character: ambitious, glamorous, and always just a little bit unstable.

Accounts from the era describe political meetings held in candle-lit drawing rooms and scandals that drifted out into the neighbouring houses. The proximity to Whitehall Palace made Downing Street the perfect base for advancing royal policies or, sometimes, plotting against them. Buckingham’s household was notorious for its extravagance, and more than once he found himself embroiled in both public feuds and clandestine court business.

His time in Downing Street was a high point—an era when the street itself was on the cusp of becoming the symbolic centre of British power. For Buckingham, it became a stage for both his ambitions and excesses, a place where Restoration London’s theatre of politics, pleasure, and drama played out on a daily basis.

To his peers, Villiers was dazzling and dangerous in equal measure. Alexander Pope immortalised him with the line: “The man who would be everything,” a nod to his relentless pursuit of status, pleasure, and power. Pope also penned a famous verse on his death:

“In the worst inn’s worst room, with mat half-hung,

The tables dingy, and the carpet torn …

Great Villiers lies—alas, how changed from him,

That life of pleasure, and that soul of whim!”

Downing Street during the time of George Villiers saw a speculative development into a hub of intrigue and power, setting a tone that would linger for generations. His legacy is built not just on the scandals and wit for which he became famous, but on shaping the very spirit of the street itself—a place where drama was never far behind the front door.

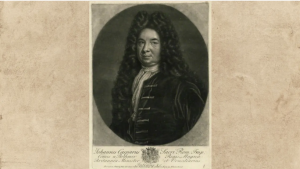

The Countess of Lichfield Richard Gibson, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The Countess of Lichfield

The Countess of Lichfield, born brought a touch of royal glamour to Downing Street in its earliest days. As the acknowledged illegitimate daughter of Charles II, she occupied the very mansion that would soon be woven into the fabric of Number 10.

Known for her warmth, wit, and social influence, the Countess transformed her home on Downing Street into one of Restoration London’s most fashionable salons. Inside those elegant rooms, the candles burned late into the night—illuminating glittering receptions where aristocrats, diplomats, playwrights, and politicians mingled under her generous hospitality. Hers was a household at the heart of the city’s social and political life, where stories and alliances were born alongside laughter and gossip.

The Countess’s receptions weren’t just opulent—they were strategic. Her father’s ties and her own place in court ensured that Downing Street was alive with whispers of statecraft and royal favour. Those who attended her gatherings may well have found themselves discussing the shifting tides of England’s monarchy, or the intrigue brewing a few steps away in Whitehall Palace.

Over time, her stately mansion became an integral part of the evolving Number 10; its walls and floors silently absorbing the legacy of power and sociability she established. The blend of personal allure and political gravity that she brought to Downing Street helped set a lasting tone for the address: a place not only where politics happened, but where people forged connections, shaped culture, and enjoyed the pleasures of London life.

Hans Caspar von Bothmer

Hans Caspar von Bothmer’s tenure at Downing Street is one of the street’s most intriguing chapters—equal parts high diplomacy, personal drama, and architectural complaint. Bothmer, the Hanoverian envoy to Britain, moved into what would eventually join the now-iconic Number 10 in the early 18th century. He was more than just a foreign diplomat; as chief adviser to the House of Hanover, Bothmer played a pivotal role in arranging and securing the accession of George I to the British throne; a saga that would change the course of British history.

From his Downing Street residence, Bothmer turned his home into a centre of international intrigue and sophisticated hospitality. He maintained stables for his prized horses—a status symbol and practical necessity for a man constantly navigating London’s political and social circuit. Inside, his salons echoed with the voices of European nobles, English ministers, and ambitious court personalities, all in orbit around one of the period’s most influential political operators.

Yet for all the power and opulence, Bothmer was never shy about airing his grievances—most notably about the “ruinous condition” of his Downing Street house. In letters and official notes, he complained about leaky roofs, crumbling plaster, and the damp that plagued so many of Downing’s quickly built terraces. It’s no surprise—these homes were infamous for their shallow foundations and rushed craftsmanship. Bothmer’s frustration was so great that his successors continued to grumble about repairs long after he left.

Bothmer’s time at Downing Street was a fascinating mix of power and inconvenience. He wielded more influence from this address than most who followed, but the daily realities of living in a poorly built London terrace were ever-present. Through grand entertainments and diplomatic scheming, and in spite of the drafty halls, Bothmer left his mark, not only on the house, but on the trajectory of British royalty itself.

Tobias Smollett

Among Downing Street’s more surprising residents was Tobias Smollett, a man whose legacy straddles both medicine and literature. In the 1740s, Smollett, a young Scottish doctor with ambitions in London—opened a medical practice right on Downing Street. Though he hoped to build a reputable career, his days as a physician were, by most accounts, not wildly successful; competition was fierce and the patients often less glamorous than Downing Street’s address might suggest.

Yet Smollett’s time as a down-at-heel doctor on one of London’s most prestigious streets did serve him well in another way: as raw material. Observing the quirks, pretensions, and private dramas of neighbours and patients, Smollett honed his eye for human folly—a gift that made his later novels both hilarious and biting. Works like Roderick Random and Humphry Clinker are full of sharply drawn Londoners, with their vanities and schemes, and it’s not hard to imagine that the bustling, socially diverse community of Downing Street offered a wealth of inspiration.

His characters often lampooned the medical profession, the status seekers, and the bureaucrats—groups he encountered daily in his failed practice. In this way, the intrigue and everyday life of Downing Street seeped directly into the pages of his satire, making Smollett not just a chronicler of Georgian society, but also one of its keenest critics.

James Boswell

In the winter of 1762, a young Scotsman named James Boswell took rooms on Downing Street. He was just twenty‑two, newly arrived in London and still years away from securing his place in literary history as the brilliant, if sometimes bumbling, biographer of Dr Samuel Johnson. At that moment, he was a law student, an ambitious writer in the making, and, by his own candid admission. a man with a taste for both serious conversation and lively diversion.

Boswell lodged with Thomas Terrie, a chamber‑keeper to the Office of Trade and Plantations, paying for a small but respectable set of rooms right on Downing Street. In his journal, he described the street approvingly as “genteel”, a word that in Georgian London meant not just tidy and well‑kept, but socially respectable, with the right sort of neighbours to impress a young man anxious to make his mark.

The location could not have been more convenient for him. By day, he could stroll to the coffee houses and legal chambers off the Strand, or to the Houses of Parliament to observe politics in action. A short walk took him to St James’s Park, the clubs of Pall Mall, or the playhouses of Drury Lane. And by night — well, Boswell was never shy about admitting that the pleasures of London after dark were as important to him as its libraries and lecture halls. From his Downing Street lodgings, he could discreetly slip into a world of taverns, theatre audiences, private salons, and less‑respectable gatherings without straying too far from home.

His journals from this period, famously frank, sometimes shockingly so, reveal the double life he led here. Mornings might find him drafting letters or recording his impressions of eminent men he hoped to meet; evenings could see him in the company of actors, courtesans, or fellow Scots chasing fortune in the capital. Downing Street, with its blend of dignity and centrality, was the perfect launchpad for this balancing act.

It’s easy to picture him at the window on a crisp evening, listening to the clip of hooves on the cobbles, watching ministers and messengers come and go, and feeling himself close, tantalisingly close, to the centre of power and culture he so admired. For Boswell, these months on Downing Street were more than just a lodging arrangement; they were a formative chapter in the making of a man who would go on to capture, like no one else, the people and pulse of his age.

V. A Street of Contrasts

For all its aristocratic associations, Downing Street was never exclusively a noble enclave. The surviving rental and insurance records tell of a more complicated social mix.

There was Count Zenobio, a politically troublesome Venetian whose residency in the 1790s ended with him being encouraged to leave the country.

There was Mary Sparrow, a widowed landlady, who owned and let several properties, including Numbers 22 and 25, to clerks, unmarried women, and junior officials.

And behind the polite facades and the grand drawing rooms were smaller, humbler spaces: servants’ quarters at the top of the house; single rooms in the attic; modest parlours for middle-class tenants whose names rarely entered the history books.

It was location, rather than pure social status, that drew people here. A senior civil servant might live two doors down from a noblewoman; a clerk might share the same cobbled street as a celebrated diplomat. In that sense, Downing Street was — even before it became a government fortress — a place where the strata of London life were pressed closely together.

VI. From Street to State Headquarters

By the early 18th century, Downing Street was a mixed neighbourhood — dukes rubbing shoulders with diplomats, writers sharing walls with civil servants. But in 1735, its destiny took a decisive turn. This was the year Britain’s political heart found its official home… and it began with a man who, rather like the street itself, had a knack for turning circumstance into opportunity.

Sir Robert Walpole is often called Britain’s first Prime Minister, though the title didn’t officially exist yet. At the time, his role was First Lord of the Treasury — a position with enormous influence. When King George II offered him the use of the house at Number 10 Downing Street, Walpole accepted — but with one shrewd condition. He insisted that the property not be a personal gift, but the official residence for whoever held the office after him. In other words, Number 10 would now belong to the state, not to any one man.

And the Number 10 we think we know today… wasn’t yet the house you would have seen then. The transformation came thanks to architect William Kent, a man who could turn modest plans into stately statements of power. Kent didn’t just spruce up Downing’s old terrace house — he joined it to the larger, older mansion at the rear, the former home of the Countess of Lichfield.

Picture this: a modest brick-fronted house on a narrow cul-de-sac that, once you stepped inside, opened up into a labyrinth of over 60 rooms. Kent linked the two buildings with a grand three-storey staircase — curved, sweeping, the kind that made you instinctively straighten your jacket as you ascended. There was a state dining room gleaming under candlelight, where political alliances could be forged over venison and claret. There were drawing rooms and reception chambers, where the very air seemed thick with intrigue. And, of course, Kent built in spacious offices, turning the residence into a functioning centre of government — a place to live and to rule.

This new arrangement set the tone for the next hundred years. Unlike aristocratic houses in more fashionable parts of town, Number 10 became a working residence, somewhere political business happened under the same roof as private life. Ministers could slip from supper into strategy sessions without even putting on their coats.

Over time, the government’s appetite for space began to spread along the street. Neighbouring houses were annexed, first for additional offices, then for ministerial residences. Number 11 became home to the Chancellor of the Exchequer; Number 12 took on various government uses — from the Colonial Office to the Chief Whip’s headquarters. One by one, the other houses that had once been let to diplomats, merchants, and writers were absorbed by the state.

By the mid-19th century, Downing Street as a social neighbourhood was gone. Only Numbers 10, 11, and 12 survived as residences — and even those were now more official than personal. The rest had been swallowed up by the machinery of government, their drawing rooms turned into offices, their bedrooms into filing rooms, their gardens paved for clerks and messengers.

It was an irrevocable transformation. What had started as a speculative terrace built on soggy ground was now the address synonymous with British leadership. Downing Street had crossed the threshold — from mixed-use London backstreet to one of the most recognisable corridors of power in the world.

And that’s where the street stayed — guarded, official, its old life erased except in the faint outlines on 18th-century maps. But as ever in London, if you scratch beneath the surface, you’ll find those earlier stories still hiding in the shadows.

VII. Change, Demolition, and Survival

By the time the Victorians left their mark on London, Downing Street had already begun its retreat into the form we recognise today. The long terrace that once stretched further towards Whitehall was shortened into the tidy cul‑de‑sac we see on the maps.

Gone was the Axe and Gate pub, a survivor from the brewery days, which had stood at the Whitehall corner for centuries, serving generations of locals, diplomats, and clerks. Gone too were many of the original houses built under Sir George Downing’s speculative eye—houses that had sheltered dukes, diplomats, writers, and radicals in their time. The steady appetite of government for offices had grown through the 19th century, and one by one the private residences were annexed or pulled down, replaced by the grand new blocks of the Foreign Office, the Home Office, and other departments of state.

But survival came, in part, from adaptation. The last three houses—Numbers 10, 11, and 12—remained standing, each with a new, overtly political purpose. Their very survival made them familiar fixtures, even as the street around them changed beyond recognition.

Then came the 20th century and another kind of trial—war. During the Second World War, German bombing raids did not spare Whitehall. Blast damage cracked masonry, shattered windows, and tested the already delicate fabric of Downing’s cheaply built terraces. The buildings limped on through the war, patched in the black‑out years, until post‑war Britain could turn its attention to repairing the heart of government.

In the 1950s, under Harold Macmillan, the decision was taken to rebuild extensively behind the preserved Georgian facades. Inside, walls were stripped back, timbers replaced, and services modernised—but from the outside, the classic black‑brick and white‑trimmed elevations remained. It was an operation that kept appearances and updated realities, a fitting metaphor for Downing Street’s entire history.

Today, those three survivors have distinct roles. Number 10 serves, as it has since Walpole’s day, as the official residence and office of the Prime Minister. Number 11 has become home to the Chancellor of the Exchequer. And Number 12 houses the Chief Whip and assorted political staff. Behind their matching fronts, each address is its own warren of offices, meeting rooms, and private spaces, humming with the daily business of government.

VIII. Downing Street Today: A Living Palimpsest

And so we come to the Downing Street of the present day—a street securely gated and guarded, a metonym for power, and a constant backdrop in the nightly news. Yet to see it only as a stage for prime ministerial briefings is to miss its richer, quieter story.

Its walls hold the imprints of three centuries of lives. The Restoration courtiers who plotted and entertained behind drawn curtains; the Hanoverian diplomats who dined and schemed; the novelists like Smollett who stitched together satire from their neighbour’s foibles; the widows who supplemented their income with lodgers; the middle‑ranking clerks and secretaries who hurried home from Whitehall offices to modest garrets a few doors away. Even the political exiles—like the outspoken Count Zenobio—left their marks in the upstairs rooms where they debated and dreamed.

When you see that famous black door, imagine the layers of history stacked behind it. Picture the medieval monks brewing ale on this plot; George Downing, the spy‑turned‑developer, cutting corners as he built his terraces; James Boswell, jotting in his journal while watching the street life below; the Countess of Lichfield hosting her glittering salons; the dull thump of a wartime bomb echoing through the corridors.

Downing Street has always been about more than politics. It has been a microcosm of London itself—merging commerce, ambition, art, intrigue, and the day‑to‑day business of living. If you know where to look, you can still read that story in its bricks, in its patchwork of alterations, and in the stubborn survival of its last three houses. The past is not erased here, merely overpainted, ready to show through whenever the light catches it just right.

If you enjoyed this episode, you may also enjoy episodes 78: Georgian Landlords and 79: Georgian Land Ladies, where my guest, Dr Gillian Williamson, and I discuss how living conditions encouraged the rise of coffeehouses and how lodging houses had their own micro hierarchy. Find out what James Boswell did to get kicked out of his lodgings in Downing Street and how a fire in Soho provided a real-life account of the assorted neighbours. Full transcript with images and transcript can be found on our website: londonguidedwalks.co.uk/podcast

That’s all we have for now. Thanks for joining us. Until next time!