Discover the intriguing details in Episode 138: Dockside Gold: How Whales Transformed London

London Guided Walks » Episode 138: Dockside Gold: How Whales Transformed London

Episode 138: Dockside Gold: How Whales Transformed London

Host: Hazel Baker

Hazel is an active Londoner, a keen theatre-goer and qualified CIGA London tour guide.

She has won awards for tour guiding and is proud to be involved with some great organisations. She is a freeman of the Worshipful Company of Marketors and am an honorary member of The Leaders Council.

Channel 5’s Walking Wartime Britain(Episode 3) and Yesterday Channel’s The Architecture the Railways Built (Series 3, Episode 7). Het Rampjaar 1672, Afl. 2: Vijand Engeland and Arte.fr Invitation au Voyage, À Chelsea, une femme qui trompe énormément.

Guest: Ian McDiarmid

Ian McDiarmid qualified as a City of London tour guide in 2017 and has a particular passion for Roman and Medieval history, having in an earlier incarnation studied history at Cambridge and London universities.

He began working life in the early 80s in the City, and has since written extensively on the share and bond markets as a journalist. He loves talking finance and taking people around the narrow alleys where today’s massive trading centre was born.

When not walking and talking, Ian enjoys pottering about in the garden. His expertise is such that he often spends several hours doing this.

Related Podcast Episodes:

Episode 27: The South Sea Bubble

Episode 101. Henry VIII’s Navy

Episode 105: St Pancras Station

Episode 96. Gas Lamps of Westminster

Episode 95. The Port of London in the Tudor Period

Episode 93. Hannah Snell, the Female Soldier

Reading List:

Re-examining Britain’s role in whaling

Shoemaker, Nancy. “Oil, Spermaceti, Ambergris, and Teeth: Products of the Nineteenth-Century Pacific Sperm-Whaling Industry.” RCC Perspectives, no. 5, 2019, pp. 17–22. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/26850617. Accessed 28 Aug. 2025.

James Colnett, A Voyage to the South Atlantic and Round Cape Horn into the Pacific Ocean, for the Purpose of Extending the Spermaceti Whale Fisheries, and Other Objects of Commerce (London: W. Bennett, 1798), 80–81.

Hacquebord, L. (2001). Three Centuries of Whaling and Walrus Hunting in Svalbard and its Impact on the Arctic Ecosystem. Environment and History, 7(2), 169–185. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20723175

Transcript:

Introduction

Hazel: Welcome to the London History Podcast. I’m your host, Hazel Baker, qualified London tour guide at londonguidedwalks.co.uk. Today we’re stepping back into a very different London – one that looked outward across the seas. Its merchant ships pushed into dangerous Arctic waters and later voyaged as far as the Pacific.

Our focus is whaling: a brutal, perilous, yet enormously important trade that shaped the city’s economy, culture, and global reach from the early 1600s through to the 19th century.

Early European Whaling

The Basque Pioneers

Hazel: The story begins not in London, but with the Basques.

Ian: Yes, the Basques were the pioneers. As early as the 11th century, they hunted whales in the Bay of Biscay. By the late 15th century, local stocks were depleted, so they pushed west to Labrador and then north to Arctic waters. Their techniques – particularly shore-based flensing and boiling – were the blueprint for all later whaling.

London’s Rise as a Whaling Port

Global Competitors

Ian: From 1600 to 1850, London grew into the largest English whaling port. By the 1780s to 1820s, it was the largest in the world, though always battling rivals: the Dutch in the 17th century, Americans in the 19th, and Norwegians later still.

Government Subsidies and Tariffs

Hazel: The industry’s fortunes were tied closely to politics.

Ian: Exactly. London’s whaling collapsed once the government reduced import duties on American oil, giving the Americans an edge. Subsidies and bounties had sustained the trade for decades; without them, London could not compete.

The Northern Fishery and Spitsbergen

Discovery of Rich Waters

Hazel: English expeditions originally sought the Northeast Passage. Instead, they discovered whales in abundance.

Ian: The key was Spitsbergen, discovered in 1596. Henry Hudson reported vast numbers of whales in 1607. Its relatively ice-free summer seas became the centre of the “Northern Fishery”.

Conflict at Sea

Ian: Competition with the Dutch was fierce. The English Muscovy Company, backed by royal patents, tried to monopolise the grounds. Armed clashes occurred, and eventually, whaling zones were informally divided.

The Muscovy Company

Monopoly and Early Voyages

Ian: The Muscovy Company, originally chartered for trade with Russia, took on whaling. They hired Basque harpooners and in 1611–12 had promising catches. But by the 1620s they were losing ground to better-organised Dutch fleets.

What Whales Were Hunted?

The Right Whale (Bowhead)

Hazel: The main target was what they called the “Greenland right whale”.

Ian: Correct – today we call it the bowhead (Balaena mysticetus). Slow, thick-blubbered, and buoyant after death, it was ideal prey. These giants lived more than a century and reached 60 feet.

Whale Products

Oil for Industry

Ian: Whale oil lit London’s lamps and was crucial in soap, textiles, and leather industries.

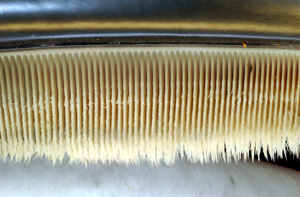

Baleen: The “Plastic of Its Time”

Hazel: Baleen – often called whalebone – had countless uses.

Ian: From corsets to umbrellas, brushes to carriage springs, baleen was everywhere. Its flexibility made it indispensable before plastics.

Fashion and Corsetry

Elizabethan to Victorian Eras

Hazel: Whale-derived fashion items are worth highlighting.

Corsetry was essential in Elizabethan times, reshaped during the Regency, and revived in extreme form during the Victorian age, with tight-lacing pushing the body to dangerous limits.

The Hunt at Sea

Brutal Techniques

Ian: Whales were chased in small boats. Harpoons were hand-thrown, attached to ropes up to a mile long. The whale often dragged the boat – the dreaded “Nantucket sleigh ride” – before succumbing. Death was slow, and processing the carcass required brutal manual labour.

Struggles of the English Industry

Parliamentary Investigations

Hazel: By 1637, Parliament was already examining why English whaling lagged behind.

Ian: The Dutch had superior ships, crews, and on-board processing. They could undercut the English in foreign markets. Declining whale stocks added to the difficulty.

Attempts at Revival

The 1690s Venture

Ian: Sir William Scawen raised £82,000 to relaunch the trade. Mismanagement and poor catches doomed it.

The 1720s South Sea Company

Hazel: The South Sea Company tried next, founding Greenland Dock in Rotherhithe.

Ian: They built boiling houses, warehouses, and equipped fleets. But the scheme faltered – again, the Dutch remained dominant.

London as the Whaling Capital

Peak of the Industry

Hazel: Despite setbacks, London boomed as a whaling port in the late 18th century.

Ian: Yes, by 1791 London fleets numbered 68 vessels. The oil and baleen trade fed directly into London’s soap makers, oil merchants, and corsetry workshops.

The Enderbys of Greenwich

Hazel: One family, the Enderbys of Greenwich, played a crucial role. They owned fleets, rope works, and sponsored Antarctic exploration. Enderby House on the Greenwich Peninsula remains as their legacy.

The Decline

American Competition

Ian: In the 19th century, American whalers flooded the market. London could not compete once tariffs were lowered. By the 1850s the city’s role in whaling ended.

Norwegian Innovation

Hazel: The Norwegians later perfected steam-powered and cannon-harpoon whaling, industrialising the slaughter into the 20th century. Whale oil even entered everyday margarine.

Cultural Memory

In Literature

Hazel: Herman Melville immortalised the Enderbys in Moby-Dick, linking their house with Europe’s royal dynasties.

In London’s Landscape

Ian: Street names, old dock basins, and houses – from Enderby Wharf to Greenland Dock – still remind us of this once-vast industry.

Conclusion

Hazel: Whaling brought wealth to London, but at immense human and environmental cost. It shaped the city’s industry, fashion, and global connections, but also drove species towards extinction.

Thank you for joining us on this journey into London’s maritime past. You can find more resources, walks, and podcast episodes at londonguidedwalks.co.uk.

John Groats | David Dixon, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Abraham Storck, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Abraham Storck, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

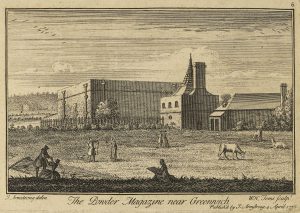

Greenwich_Peninsula | J. Armstrong; William Henri Toms, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Sperm Oil | Raphael D. Mazor, CC BY 2.0

Baleen | Anon at NOAA Fisheries Service, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Baleen Whale | PaleoNeolitic (montage creator), CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons