When we think of women in the 18th century, it’s easy to picture them as passive-figures —decorative, domestic, and destined for marriage. But this narrow view overlooks the remarkable women who shaped the commercial heart of London.

18th century women are commonly depicted in literature and art as being purely decorative and waiting for marriage and in terms of trade, women are seen only as consumers of luxury goods. However, think again!

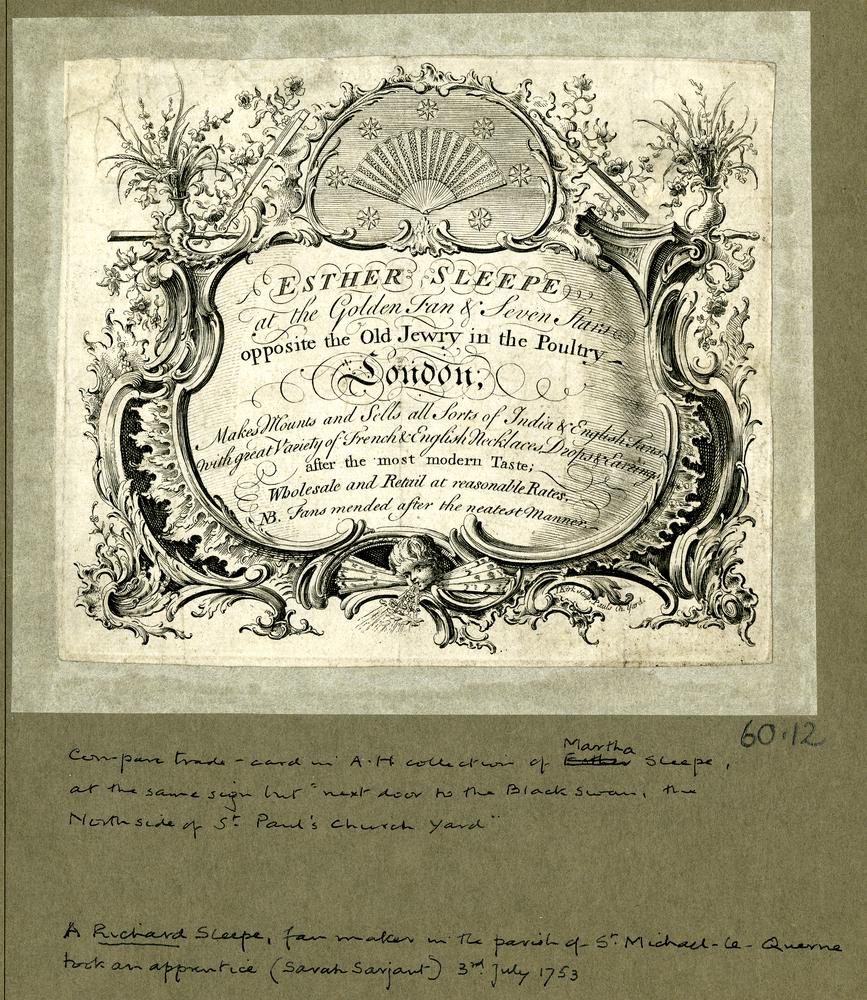

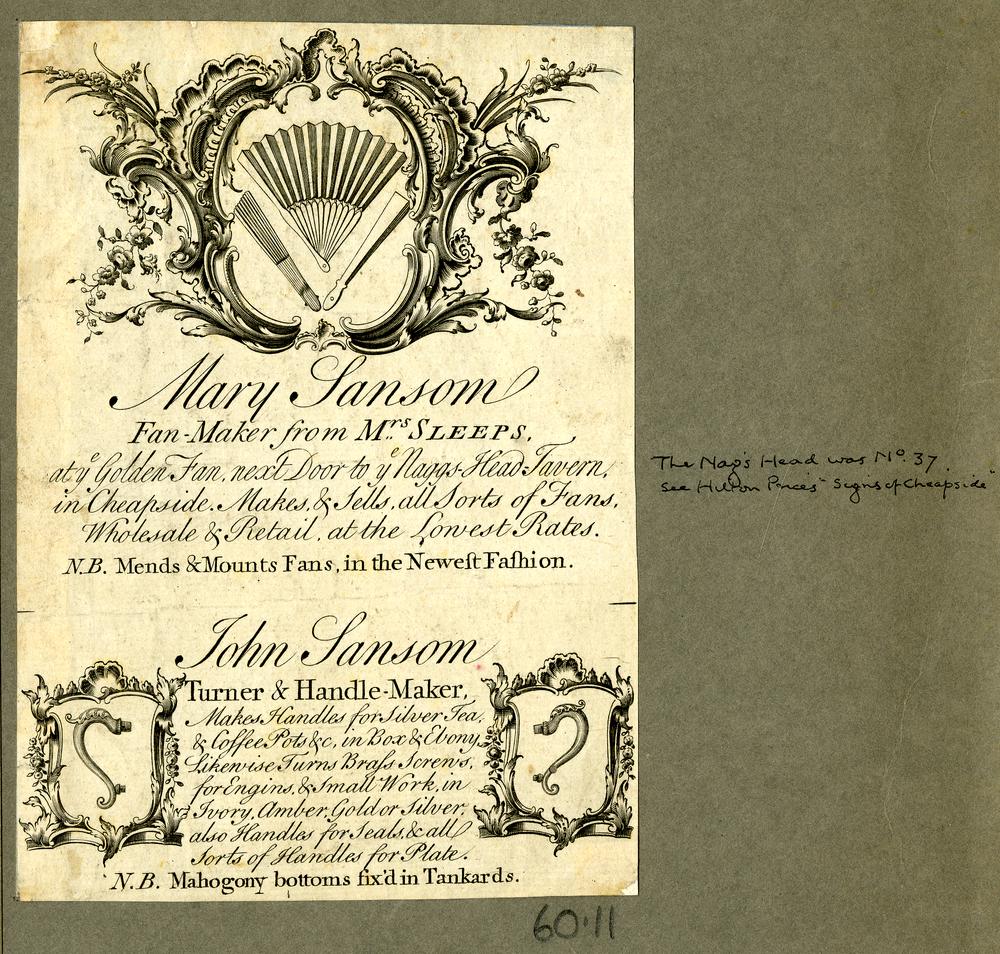

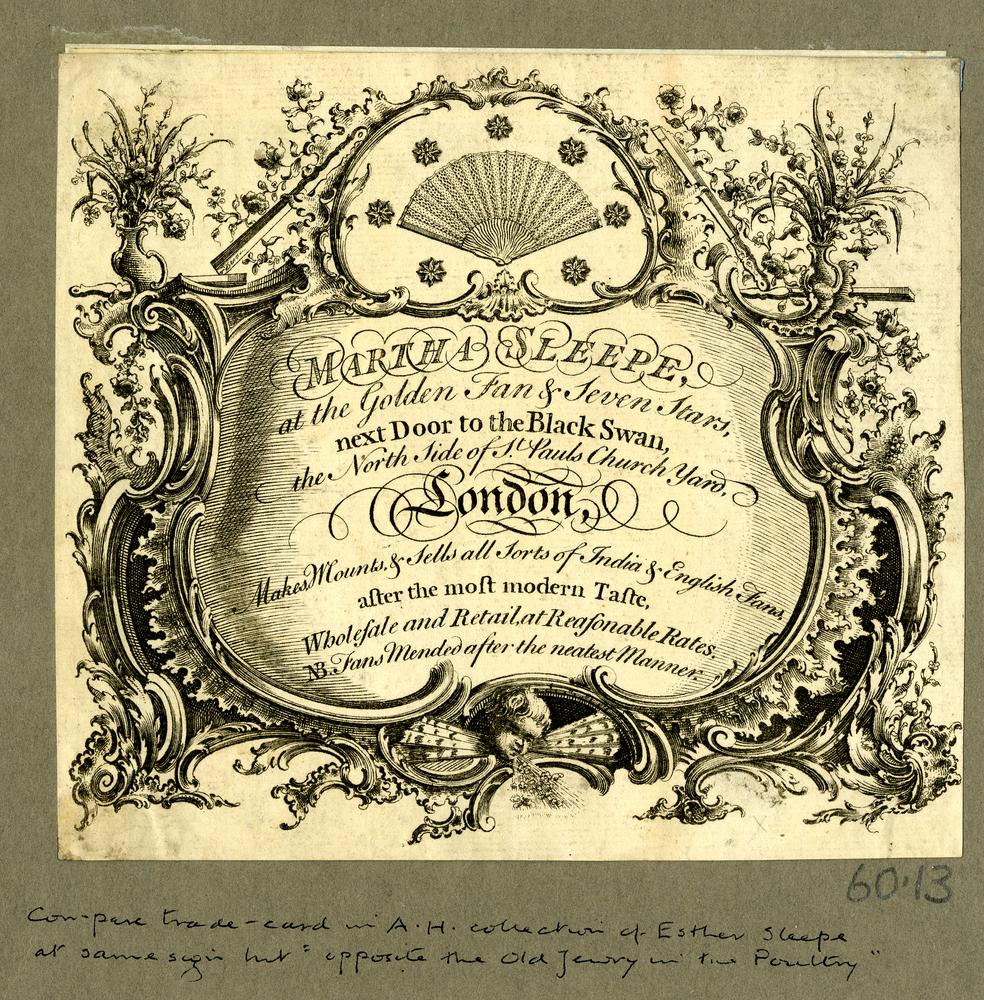

The British Museum has a fabulous collection of trade cards, these are beautifully drawn and illustrated advertisements, promoting trade in the City Of London in the 18th century and 75 of these cards are promoting female entrepreneurs and women who had their own very successful businesses and workshops in the City of London.

Cheapside as a Commercial and Female-Driven Hub

Many of these women worked out of Cheapside. The name of the street—Cheapside comes from the Anglo-Saxon word meaning market, and for hundreds of years Cheapside has been an area of luxury shopping and retail.

The Goldsmiths had their shops and workshops here as their Livery company Hall was round the corner in Foster Lane. Three of these business cards belong to the Sleepe sisters, all members of the same family who were fan makers.

Women in Trade and Commerce

All three had their own fan making workshops and shops in which to sell their wares on Cheapside — and all had been trained up by their mother Mrs Francis Sleepe, who also had her own fan making business all whilst bringing up a family of 15. Sadly, only five of whom survived into adulthood. The Sleepe sisters operated under the business name of “the Golden Fan and Seven Stars”.

Esther Sleepe’s business was on Old Jewry opposite Poultry, Mary Sansom Sleepe’s was on Cheapside next to the Nag’s Head and Martha Sleepe’s business was on the north side of St Paul’s Churchyard by the Black Swan.

Fans as Functional and Symbolic Objects

At that time there were no numbered premises and so people would use a place nearby; a pub, a church or an in for example, to let you know exactly where their business was situated. We know from the Sleepe sister’s business cards that all three “repaired and mended fans in the neatest fashion”, that Esther also sold jewellery from her shop and that all three sisters made fans “both India and English”.

So not only were the Sleepe sisters selling their fans in London, they were also exporting their fans to and from the British colonies. Fans were an intrinsic part of women’s fashion and a “must-have accessory for women”. The fan was an extension of a woman’s personality and was used as a means to convey emotions and feelings towards the person they were talking to.

This is well summed up by Soame Jenyns—an English writer and MP for Cambridgeshire. In his poem “The Art of Dancing” he sums up the ‘Language of the Fan’. He talks of the fan as being “a powerful little engine“ that has “numerous uses, motions, charms and arts. Its shake triumphant, its virtuous clap, its angry flutter, and its wanton tap”.

People started to make printed fans, and these were used for many purposes; to advertise, to instruct or to depict and commemorate a historical event: a printed fan was made to announce the playing of Handel’s Royal Fireworks music in Green Park commissioned in 1749 by King George II.

Artistic and Cultural Value

The music was accompanied with a dazzling firework display. But fans had many other purposes. Worried about conversation drying up at a supper party? A printed fan with rhymes and riddles on it will help to keep the conversation going.

Worried about saying the wrong response is in a church service? No problem! A printed fan with all the correct prayers and responses will keep you from embarrassing yourself in church. Been invited to a Ball but unsure of the steps to the latest dance? No problem! Buy a printed fan with all the dance steps written on it and your dance card will soon be filled completely.

The story of the Sleepe sisters offers a powerful reminder that women have long played a vital role in shaping commerce, culture, and craft. It’s time to reframe our view of the 18th century and recognise the women who helped make history—one fan at a time.

Ready to hear the remarkable stories of women in the City of London whose contributions helped the City of London become the global financial powerhouse that it is today?

📍 Book a Private Power, Profit, and Progress: Women in the City of London tour with Jenny now!