Introduction:

London and the Legacy of Whaling: Illuminating the City, Reshaping the Arctic

Throughout the seventeenth to nineteenth centuries, London stood at the epicenter of the British—and, for a time, the world—whaling industry. The city’s bustling docks, riverbanks, and refineries became gateways for flows of blubber, oil, spermaceti, baleen, and walrus ivory, turning the capital into a powerhouse of commodity transformation. But the consequences of London’s trade in the North Atlantic and, eventually, the wider world, reached far beyond economic bustle—they reshaped distant ecosystems and left imprints on both natural and urban landscapes.

A Whaling Port Emerges

London’s rise as a whaling port began in the early 1600s, as English merchants vied with the Dutch and others for access to Arctic riches. With the founding of the Muscovy Company and successive government monopolies, London-based investors sent fleets to hunt the Greenland right whale (bowhead) and, later, the sperm whale in ever more distant seas. The city’s Greenland Dock (originally Howland Great Dock, built in the 1690s), Rotherhithe, and adjacent quays on the Thames became scenes of offloaded carcasses, busy “blubber houses” rendering oil, and the unmistakable stench of industry.

By the mid-1700s, London controlled well over half of the British whaling fleet. Whale oil fueled not only street lamps that bathed the city in light but also a growing domestic market for candles—especially those made from spermaceti, prized for their bright, odorless, smokeless flame. London’s merchants, like the Enderby family, organized Pacific whaling expeditions and linked the city to distant extraction zones from Spitsbergen to the South Seas.

Transforming the World—One Whale at a Time

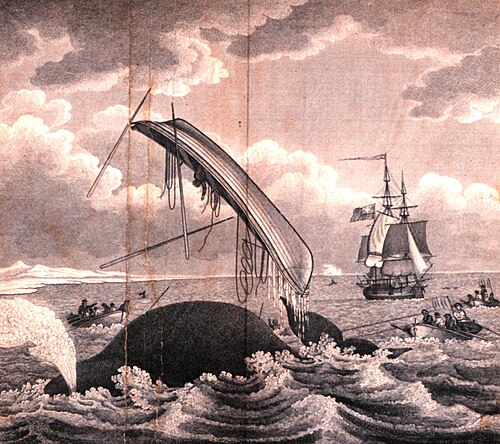

Ships departing from the Thames targeted Arctic bowheads and walrus, harvesting tens of thousands over three centuries. The Greenland right whale, a baleen whale thriving in the ice-choked waters around Svalbard, was especially valued. Historical catch records and archaeological remains show the intensity of this hunt: by 1850, London’s and Europe’s fleets had extirpated bowheads from the region, removing 46,000 whales from the ecosystem and dramatically altering the marine food web.

As the Atlantic walrus population was similarly decimated—25,000 animals lost—huge volumes of plankton and shellfish that had once nourished these giants became available to other predators. Modern biological studies suggest that this bounty triggered a surge in smaller plankton-eating birds (like the little auk) and fish, and, in turn, their predators—a ripple effect stemming from London’s demand for lamp fuel and fine candles.

Commodity Chains and Cultural Connections

In London, whale products underwent further transformation. Whale oil was rendered and refined in Thames-side facilities and traded through standardized weights and grades, feeding a commodity market where provenance mattered less than purity or price. Spermaceti was crafted by specialized chandlers into premium candles, the illumination of choice for the city’s affluent and influential.

Yet not all products followed the same route. Ambergris, occasionally recovered from sperm whales, fetched exorbitant prices for use as a perfume fixative. Whale teeth, meanwhile, entered niche markets. Although rarely claimed as official cargo, they became precious gifts in the Pacific—symbols of wealth and power in Fijian and Tongan societies, and canvases for scrimshaw art among whalemen. London’s ships, provisioning for Pacific trade, often carried barrels of these teeth along with sandalwood and other exotic goods, linking metropolitan tastes to distant cultures.

The End of an Era and Lasting Legacies

London’s dominance waned as resources diminished, government bounties ended, and other ports rose to prominence. By the late 1850s, whaling activity on the Thames had all but ceased. Yet its legacy remains—in maritime museums, the antique trade in scrimshaw and ceremonial tabua, and in the ongoing ecological transformations of places like Svalbard.

Modern legal frameworks, such as CITES and the International Whaling Commission, arose as direct responses to the depletion wrought by centuries of unregulated hunting—much of it orchestrated, processed, and consumed in London.

London’s whaling story is one of industrial innovation and relentless global reach, illuminating the city and transforming distant seas. It is also a cautionary tale of interconnectedness, how a metropolis’s appetite for light, luxury, and trade helped drive dramatic shifts in marine ecosystems, felt from the Thames to the Arctic Circle. The city’s historic docks have been redeveloped, but their ecological shadow and cultural resonance endure.

Listen to Episode 138: Dockside Gold: How Whales Transformed London on the London History Podcast to discover more about this fascinating chapter in the capital’s past.