Introduction

Every lane and street in the City of London tells a story, which is unsurprising as its history goes back from 43 AD from when the Romans called it Londinium to the present day where it is the financial heart that drives the UK’s economy contributing about 22% of the entire country’s GDP. Not bad when you know that the City is known as The Square Mile – and that is exactly what it is – just over a square mile in size – 1.12square miles in fact or 2.9 square metres.

Cornhill’s Roman and Topographical Roots

The area I am going to talk about today is Cornhill.

When the Romans occupied Londinium there were two substantial hills in the city (three if you count Tower Hill), and two rivers. The rivers Walbrook and Fleet are now both underground and can only be seen going into the Thames at very low tide; and the two hills were Ludgate Hill which is now grazed by St Paul’s Cathedral, and the second Hill was Cornhill which is now where Leadenhall market is situated.

📖Have a read: The Old St Paul’s Chapter House: An Architectural and Historical Gem

🎧Listen now: Episode 102. Characters of Leadenhall Market

Whilst walking up both these hills today, one doesn’t seem to notice a steep hill on either spot, although perhaps Ludgate going up to St Paul’s is more of a hill than the gentle slope that goes up Gracechurch Street to Leadenhall market on Cornhill. However what we have to take into consideration is that Roman pavement level is a good 26 feet-or nearly 8 metres below our current pavement level. Thus making those hills more substantial to the Romans than they seem to us now.

Today Cornhill is in the ward of Cornhill. The Anglo-Saxons divided the City of London into 25 different wards, each one overlooked by an Alderman or ‘Ealderman’ which means Wise man. These words still exist today and they are still overseen by an Alderman-and the court of 25 Alderman (a few are women!) Sit in their own court in Guildhall where they play a large part in the governance of the City of London and in the election of the City’s Lord Mayor.

Cornhill was called such as this was where there was a corn market. A market for grains and other food stuff took place here and it dates back to the 14th century where it was known as a prominent market street with the corn market at its eastern end (Gracechurch Street) and a general market which was held in its main street .

The Royal Exchange and Early Shopping

Cornhill is also home to the Royal Exchange – England’s first trading bourse or floor, built by Sir Thomas Gresham in 1571, a businessman. Gresham also built two floors of shops inside the Royal Exchange which he would charge rent. It was opened by Elizabeth I in 1571 and was the country’s very first Elizabethan shopping mall.

Coffee Houses and Commerce

Cornhill is a key financial district – many of the City’s Coffee Houses were situated in Alleyways off Cornhill – and in these Coffee houses, tradesmen would meet to pass on news, discuss business and make financial transactions.

Dickens and the Counting House

It is here where Bob Cratchit, Scrooge’s down-trodden clerk, ‘went down a slide on Cornhill, at the end of a lane of boys,twenty times, in honour of it being Christmas Eve. It is also where Charles Dickens places Scrooge’s Counting House in ‘A Christmas Carol’ written in 1843. Dickens tells us that Scrooge’s counting house is within an ancient tower of a church, ‘whose gruff old bell was always peeping slyly down at Scrooge out of a gothic window in the wall.’

🎧Listen Now: Episode 40: Charles Dickens in Greenwich

🎧Listen Now: Archie’s Journey Through Dicken’s London

Wren Churches and Christian Origins in Cornhill

Cornhill, at the historic heart of the City of London, is remarkable not only for its rich mercantile associations but also for hosting two celebrated Christopher Wren churches—each with deep roots reaching back into London’s earliest Christian history.

St Michael Cornhill

St Michael Cornhill stands as an elegant example of Wren’s post-Great Fire church restoration. The current building, attributed to Sir Christopher Wren, rose after the medieval church was destroyed in the Great Fire of 1666. Its origins, however, stretch further back: records of a church dedicated to St Michael on this site exist as early as 1055, when Alnothus the priest gifted it to the Abbot of Evesham. The church’s location is significant: it is set directly above the remains of the Roman Basilica—the ancient administrative and trading centre of Londinium, built in the first century AD. This physical foundation on Roman remains evokes the layered endurance of spiritual and civic life in London.

The church itself has been associated with famous figures across the centuries, from Robert Fabyan, a chronicler of England and France, to Thomas Gray, author of “Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard,” who was baptised at St Michael’s. The church was carefully restored and embellished throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, with its tower completed by Nicholas Hawksmoor, Wren’s distinguished associate.

St Peter Upon Cornhill: London’s Oldest Christianised Site?

Nearby, St Peter Upon Cornhill lays claim to one of the most extraordinary legacies in London: tradition holds that it is the oldest Christian place of worship in the city. According to church records and historical tablets, the site is believed to have hosted a Christian congregation since 179 AD, when Lucius, reputed to be the first Christian King of Britain, founded a church here. Though some historians question the veracity of these origins, there is no doubt that St Peter’s marks an ancient sacred site, sitting at the highest point in the City of London and backed by continuous evidence of religious worship since the Roman era.

The legend of King Lucius is widespread in medieval chronicles: he is said to have requested Christian missionaries from Pope Eleutherius, and upon his conversion, founded churches across his realm, with St Peter’s regarded as the chief church of his kingdom. Archaeological and documentary evidence confirms activity on this site for centuries, even if the Lucius narrative remains part legend, part history.

Following the destruction wrought by the Great Fire, Wren rebuilt St Peter’s church, though its proportions are now somewhat reduced from earlier times. The Wren building retains elements thought to be designed by his own hand as well as later restorations.

Christian Origins and the Medieval City

Both St Michael Cornhill and St Peter Upon Cornhill remind us that London’s religious heritage is woven into the very fabric of the City. These churches, rooted in Roman-era sites, endured the best and worst of London’s fortunes—from medieval prosperity to fires and wars. Their survival and continued use speak to a remarkable continuity of worship spanning almost two millennia.

📘Have a read: St Peter’s Cornhill: a Church Hidden from the Street

Luckily for us, having been rebuilt by Sir Christopher Wren after the Great Fire of London in 1666, it narrowly escaped the bombing in the Blitz ( September 1940 – May 1941) and is one of only 13 unspoilt Wren churches.

🎧Listen Now: Episode 20: The Great Fire of London – How It Began

The Cornhill Devils: A Gothic Tale of Revenge

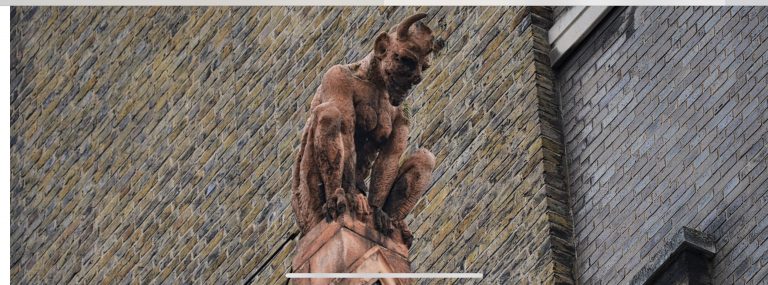

And it is this church – or rather the building next to it which has a very interesting history. Most of us, when dashing through the City, are racing from A to B without looking up or really seeing our surroundings. However when next walking past number 54 and 55 Cornhill you may suddenly be filled with a feeling of unease – a shudder down the spine – a feeling of being watched or under surveillance from something unseen.

Stop for a moment and look up – there you will see a devilish creature with a face full of malevolence and evil – perched as if about to spring down and pounce – then you will notice a second – and behind this is an even smaller one- but it is by far the most satanic – and it is glaring right down into St Peter’s church next door – one of the oldest sites of Christian worship in the City – built on the site of the Roman Basilica .

Then you may notice two more stone devils carved into the building – these stone and terracotta creatures are known as the Cornhill Devils. These satanic creatures were added on to the building as an act of revenge by the architect who had fallen out with the vicar of the church next door.

Architect Ernest Runtz (1859 -1913) inadvertently allowed his finished design of Number 54-55 Cornhill to encroach a little onto the land of the adjoining church, St Peter of Cornhill. When the vicar of the church realised this he was furious at the loss of land and made a huge fuss which saw Runtz having to go back to his drawing board and redesign his plans. The building was built in 1893.

Ernest Runtz was not best pleased with this – and, understandably, blamed the Vicar. Relations between the two men became strained and so when the building was completed, Runtz decided to have one last parting shot – and so he commissioned these three demonic stone effigies to surround his building.

The smallest devil has its mouth wide open and it appears to be howling down on St Peter’s Church and, in a final act of revenge, Runtz apparently had this most evil looking of devils modelled on the facial features of the Vicar himself – and this is why they are here gazing down on St Peter’s spitting their eternal curses onto the church. Revenge indeed.

Book a City Highlights walk or a private City of London Highlights Tour with me and hear more about this ancient City, its lesser-known lanes, its secret gardens and its fabulous buildings.