The Canterbury Tales is Geoffrey Chaucer’s most famous work, written in Middle English between 1387 and 1400, and is widely regarded as a cornerstone of English literature. The collection is framed as a storytelling contest among a group of pilgrims journeying from Southwark, just south of the River Thames in London, to the shrine of Saint Thomas Becket at Canterbury Cathedral.

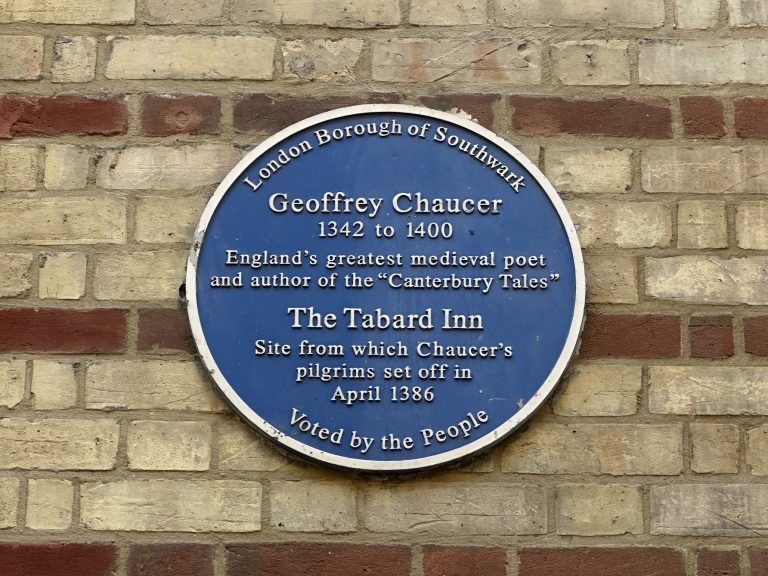

The pilgrims gather at the Tabard Inn, a real and well-known establishment in 14th-century Southwark, which Chaucer describes as spacious and welcoming for both travellers and their animals. The inn, managed by the genial host Harry Bailly, serves as the starting point for the journey and the narrative. It was a fitting choice for Chaucer, as the Tabard was a crossroads for people from all walks of life—pilgrims, merchants, and even more unsavoury characters—reflecting the diversity found in his cast of characters.

At the Tabard, the host proposes a storytelling contest to entertain the group on their way to Canterbury, promising a free supper at the inn for the teller of the best tale, as judged by himself. This lively setting, with its mix of social classes and personalities, provides the perfect backdrop for Chaucer’s vivid portraits and enduring stories.

In The Canterbury Tales, food and drink serve not just to sustain, but to reveal. Chaucer’s characters are defined as much by what they consume as by what they say. Appetite becomes identity—something as human in the 14th century as it is today.

Why Start a Pilgrimage at the Pub?

It might seem odd that The Canterbury Tales, one of the greatest works of English literature, begins not in a cathedral or chapel, but in a bustling Southwark inn. Yet Geoffrey Chaucer knew his audience well. In 14th-century London, the Tabard Inn was more than a stopping point; it was a crossroads for travellers, a stage for stories, and a place where appetites—culinary and otherwise—were openly indulged. Here, over bread, ale, and the promise of a hearty meal, Chaucer’s pilgrims gather, their journey fuelled as much by food and drink as by faith. In Chaucer’s world, as in ours, the shared table is where stories truly begin.

Chaucer’s Southwark: A Lively Threshold

Southwark in the late 1300s lay just beyond the formal boundaries of the City of London, across the river and outside the reach of the city fathers. It was a place of theatres, brothels, coaching inns, and market stalls—a district humming with movement and exchange. Borough High Street, the main southern approach to London Bridge, was the natural gathering point for pilgrims and merchants alike.

The Tabard Inn, once found on this very street, catered to those setting out for Canterbury. Though the original building is long gone, the street’s character remains: a threshold between the sacred and the everyday. Chaucer’s pilgrims—some thirty-odd characters, from the noble Knight to the earthy Cook—gather here to eat, drink, and tell tales before their spiritual journey begins. And crucially, Chaucer opens with food. It is not prayer that binds them, but a shared table.

Food and Drink as Social Commentary

Chaucer uses food not only to flavour his tales, but to reveal personality, status, and moral standing. Characters are introduced through what they consume—or what they refuse to.

Take the Prioress, for example, whose dainty manners are gently mocked through her over-polished table etiquette. She refuses coarse fare, feeds her dogs white bread and roasted meat, and lets crumbs fall with elegant disdain. Chaucer hints at spiritual emptiness masked by surface refinement. As he writes:

“Of smale houndes hadde she that she fed / With rosted flesh, or milk and wastel-breed.”

Contrast this with the Miller, a brawny brute with a thirst for ale and a preference for bawdy tales. His coarse humour and physical appetite go hand in hand—he is built for strong drink and strong opinions. The Cook, skilled in roasting, boiling, and baking pies (“bake mete”), is ironically described as having a festering sore on his shin—perhaps a sly nod to the less savoury aspects of medieval kitchens and the blurred line between bodily and culinary appetites.

Then there is the Pardoner, perhaps the most cynical figure in the group, who admits:

“I preche of no thyng but for coveitise.”

His priorities? Money, meat, wool, and wine.

The Innkeeper as Storyteller’s Ringmaster

Harry Bailly, the landlord of the Tabard Inn, acts as the glue binding these travellers together. He proposes the storytelling competition and judges the winners. As an innkeeper, he represents the link between hospitality and narrative—how food and stories go hand in hand. The prize for the best tale? A supper at the inn, paid for by the other pilgrims—a detail that underscores the centrality of food as both motivation and reward.

Harry’s voice is not elevated, but earthy, grounded in banter and practical wisdom. He is a Southwark figure through and through—direct, jovial, and used to managing groups with diverse appetites.

Medieval Diets and Moral Lessons

Food in The Canterbury Tales is not only physical—it is metaphorical. Gluttony is frequently satirised, but so is false piety. Chaucer suggests that those who deny the body entirely may be just as flawed as those who indulge it too much.

The tales often blur the line between body and soul. The Cook’s Tale, though unfinished, begins with a moral decline that starts with too many pints and too little purpose. Meanwhile, the Franklin, a landowner, is praised for generosity at his table—“His table dormant in his halle alway / Stood redy covered al the longe day.” He embodies the idea that sharing food is a social duty, not just a pleasure.

Medieval diets were shaped by class and occasion. Bread and ale were staples for all, but white bread and roast meats were luxuries, as seen in the Prioress’s preferences. The Franklin’s table “snewed” (snowed) with meat and drink, and meat pies filled with currants and dates were treats for the well-to-do.

Walking with Chaucer in Southwark Today

Today, the site of the Tabard Inn is marked by a quiet courtyard off Borough High Street. Most pass it without noticing. But with a little guidance, you can still feel the atmosphere of Chaucer’s Southwark—a place of trade, travel, appetite, and entertainment.

A walk through Southwark brings you into contact not just with the ghosts of pilgrims, but with their desires. From the bustling stalls of Borough Market—whose roots stretch back centuries—to tucked-away pubs, the modern echoes of Chaucer’s medieval world are easy to spot. Londoners still seek warmth, food, and companionship—and still share their stories over a drink. 📚Read more: Things to do in London: Borough Market

“And specially, from every shires ende / Of Engelond, to Caunterbury they wende, / The hooly blisful martir for to seke, / That hem hath holpen, whan that they were seeke.”

Whether for healing, hunger, or the sheer joy of company, Chaucer’s pilgrims—and today’s Londoners—know that every journey begins best with good food, good drink, and a tale well told.

So next time you’re nibbling cheese from a Borough Market stall or sipping ale near the river, remember: Chaucer saw the table as a theatre. And in Southwark, the show still goes on.

📍Join our Southwark Walk

Step into the world of Chaucer, Dickens, and the Thames-side dreamers. Available as a public guided walk or private tour. Expect history, humour—and a few well-placed pub recommendations.