What do Jamie Oliver, Queen Victoria and harps have in common? Find out on our latest episode where Moira Bonnington talks with Hazel about her investigation into four generations of harp makers in Fitzrovia.

Recommended Reading:

Show Notes:

Hazel Baker: Hello and welcome to London Guided Walks London History podcast. In the coming episodes, we will be sharing our love and passion for London, its people, places and history in an espresso shot with a splash of personality. For those of you who don’t know me, I am Hazel Baker, founder of London Guided Walks, providing guided walks and private tours to Londoners and visitors alike.

Hazel Baker: Hello and welcome to London Guided Walks London History podcast. In the coming episodes, we will be sharing our love and passion for London, its people, places and history in an espresso shot with a splash of personality. For those of you who don’t know me, I am Hazel Baker, founder of London Guided Walks, providing guided walks and private tours to Londoners and visitors alike.

Don’t forget to accompany this podcast we also have really great show notes, including pictures, and this time a map. We have London history-related blog posts for you to enjoy, absolutely free. And of course, now we have The Daily London, providing you with a couple of minutes of daily inspiration for things to do in London for Londoners. You can listen on iTunes, Spotify, add it to your Alexa flash briefings. All the information you need is on our website londonguidedwalks.co.uk/flash.

Joining me in the studio today is Moira Bonnington, who has gone on a little bit of an adventure, really with her family history and has uncovered four generations of harp makers in London. And I’ve invited her here today to share her adventures and some of her findings.

I must admit Moira, I got very excited when I read your research about your family history. Because it’s not just about the streets of London, this is about the people that lived and worked in them as well.

Moira Bonnington: That’s exactly how my interest started, Hazel. I knew my granny was born in Melbourne and, as a child, she would take me up and talk about places she knew. But of course you never remember all that long after people are dead and gone. You wish you’d asked all these questions, but the censuses, which are now online in various Genealogical sites weren’t readily available. I managed to get a hold of one and I was absolutely fascinated because I knew addresses where they lived and I could walk up and down the street, literally walk up and down the street on the computer. And I knew who was living in the house next door and what they would be doing. And I found of course, all sorts of famous people lived in the area where my ancestors lived.

It’s now fashionably called Fitzrovia, but in those days it was a place where a lot of working people around the Middlesex Hospital in between the Middlesex Hospital and Tottenham court road were lots of little workshops and it attracted a lot of people from European backgrounds. And they were, actually it was quite a big German population. And the people in these workshops, funnily, it was furniture making and cabinet making and a lot of musical instrument makers and they worked in the mirrors behind the buildings. But it’s a good example of how you have to work fast when you get lead like this because the Middlesex Hospital in the 20 years I’ve been looking at that area has been demolished totally. The church where my grandmother and a lot of her ancestors were baptized, which is next to all the new news. Holy Trinity church, at the top of Tottenham court road and became an SPCK bookshop. And then it was deconsecrated totally. And I think it was a nightclub at once. You walk along these streets, hoping you’ll see, don’t you? The buildings that you you’ve imagined, and they’ve no longer there.

Hazel Baker: No. Your interest in all of this, Moira, started I believe from an old Brown envelope? Isn’t that right?

Moira Bonnington: Where did you found out? Have you been, have you been Googling me?

Hazel Baker: I’ve been Googling you and I love this little story, you know, it’s all about, how people get on the path, you know?

Moira Bonnington: Yeah, exactly. So.. You can see I was so enthusiastic. I went off on this great trail and, yeah, for a while, I published things all over the internet and found seven hops with my family name and several cousins that I didn’t know about.

Hazel Baker: Wow.

Moira Bonnington: So, yes, it was it’s quite a nice thing to do. And lockdown, of course, if you have the time, you’ve got the time to do these things again.

Hazel Baker: Well, why don’t you tell the listeners about the Brown envelope that your father gave you?

Moira Bonnington: My father met me at a pub once, lunchtime, and he handed me this brown envelope. And in it, it had my grandmother’s birth certificate and marriage certificate. And it had a picture of this old gentleman holding this harp. I’d never seen him before and his great white beard. He looked very interesting. And he said, there you are, I think you might find that interesting. But one of the articles and one of the bits of paper that was in there was a very torn newspaper article about a man called Morley.

And Mr. Morley had a shop and it was full of harps. And, he said, Oh, your grandfather knew this chap. Well, I went home and, straight away I was on the internet and believe it or not, I found out that there was a chap called Morley who still had a harp business. So I was on it straight away. And Clive Morley had, he and his brother or cousin, I’m not sure that now, had separated the family business and one concentrated on pianos and the other on harps. And they had bought up the family business in 1926 or there about when the last of the harp family, which was my family name, died. And it turned out that there had been some records that they’d taken over, businesses like that had very, very detailed records. And in fact, the records of the era factory, which was the major producer of harps in London at that time are all in the Royal College of Music Archives. And they sent them all over the world. They put them in big packing cases and sent them off to Russia and Canada and all sorts of places now.

Along with the other bits of information I found, I found out that this family, my family, which had this very unusual name had been producing harps for, I could go back as far as 1808, believe it or not. When my great, great grandfather, Henry David, boasted that his grandfather had, made harps in the errad manufacturer, which was in Great Mulberry Street.

That’s roughly where the Royal Palladium is now. There’s a theatre there and Sebastian had come over to escape the French revolution.

Hazel Baker: That’s right. He provided harps for Marie Antoinette, hasn’t it?

Moira Bonnington: He did, he did indeed. He was a pioneer in making these harps more accessible to amateur players as it were. So he, instead, he put in various refinements so that the harps were more modern. And these, the technical business of working out how to do this was, the responsibility of one of my ancestors who was called Christian Harnack.

Hazel Baker: These are prototypes then?

Moira Bonnington: Yes, this is why it’s tip top technology of the time, because the piano’s fault wasn’t popular at that time. And so, all nice young ladies learn the harp because it was very attractive thing to sit there and harp was very popular in drawing rooms, but it didn’t actually make the sound loud enough to project into big concert halls and they wanted to make it more usable for that kind of situation. And so they employed lots of methods of making the harp stronger and so on and so forth. And there was a race between competitors at the time to put in patents and patent these new harps. And it was about that time when they developed something called the Gothic harp which is the picture of harp. If you look at the old gentleman in the picture I posted. That is a Gothic harp. I’m not sure whether my great-great-grandfather is playing one of his own harps or one that had come into the shop.

Because the Aaron’s made harps for the Royal family, they sort of, it was like a franchise, you know, other people made half in the same style. And that was what my family did because they’d worked for various harp makers and it had apprenticeships and so on and so forth. And it’s a very complicated process. I have since visited various harp makers who does some repairs through the last few years. And biggest one is Pilgrim Harps, which is down in Sussex.

And Pilgrim Harps make modern harps and repair these ain’t old harps. And there’s lots of processes involved. You have to be quite a good technician because inside that column, there are lots of rods and springs and levers, and bits and pieces. So there were people who had to make all the sort of metal bits and sought that out. But there are also carpenters who had to make the soundboard, which is that big board underneath where the strings go through. And then of course, there’s that lovely swan neck bit at the top. And then there would be guilders and there would be people who would engrave the name on the brass plate at the top.

And my imagination’s run right, but I could see these people putting the harp into a wheelbarrow and really down the dark alley to the Joe Bloggs down the road to do a little bit gilding for them and so on and so forth. When those harps went out to the theatres, a harp has to be re-tuned almost every day, every time it’s played.

So you can imagine them running backwards and forwards between the theatres and whatever. With these harps and providing them. And it was a very busy sort of place. Naturally, my first visit to London, I walked up and down these alleyways in Charlotte St and in the Newman St next door where my ancestors lived and tried to imagine what it would be like.

Now, the funny thing was I didn’t watch much television while I was doing all this work. But one day I noticed this program called The Naked Chef. And I hadn’t heard of Jamie Oliver at the time. It shows you how long ago it was, but Jamie Oliver strode down this street in the way that he used to do and pushed the orange door of this restaurant, where he used to work and went in to see an Italian chap.

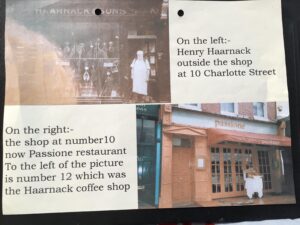

And over the door, it said Passy only, but more importantly, it said number 10 and it was Charlotte St. So I rattled through my photographs that I’d taken the week before when I was in London. And I thought that’s my grandfather’s shop. What a coincidence.

Hazel Baker: It’s so lovely how the layering of knowledge, you know, brings you to that place? You know, having been there, you’ve made a real life connection to the place, you know? And then suddenly it’s like Velcro, isn’t it? Your eyes are open.

Moira Bonnington: Oh, you suddenly see it in different ways. So the next thing of course was to contact them from who’d made the little film for the television and that was called optimum.

And they said, Oh no, this is the days of old video tapes. Videocassette. I said, sure enough, we’ll post you a copy of the film. Which they did kindly and I could stop it down and freeze it and take a picture. And of course I so much wanted to open that door and he opened the door and there was my grandfather standing there.

As you can see in the picture, the Victorians had this fad, didn’t they for going around and taking pictures of shopfronts. And they would, people have told me that they would put the camera on a sort of wheelbarrow construction, wander down the street and call up photos or something like that. And out you would come and that picture sort of reinforces that because there’s a chap with an apron on, he’s obviously been working and the dog looks very surprised.

Hazel Baker: So it’s all the maths as well, you know?

Moira Bonnington: Oh, well, I better stop what I’m doing, but it would be good advertisement for the shop because he’s come out and stood on the doorstep. And it ties in with so many other things, because if you enlarge that picture, it says . And my granny all was said that she spoke French. So what’s the next connection. My granny had a sense of history. She had an album full of embroidered postcards from the first world war that had been sent back to her by her husband.

And I don’t know whether you’ve ever seen them. There’s a little flap inside and inside it says from somewhere in France, they’re never allowed to put any messages in them. And, So I think I must’ve inherited through my genes for enthusiasm for this kind of thing.

Hazel Baker: Yeah. That’s fantastic. Is it your great great-grandfather? Who was 93 when he was still in the shop?

Moira Bonnington: Yes. He was.

Hazel Baker: That’s phenomenal. And he started at what? The age of 11?

Moira Bonnington: There was a newspaper that interviewed him at the time and he was still working and, Well, I wouldn’t give up. They were a very sort of tough family and they survived through thick and thin and he was still working in the shop.

My grandmother was born in 1886 and I knew her. She died when I was about 20 in my head. I can go back to the previous, not the previous century, the century before that. What she told me about it when she was a child. And similarly, I got another coincidence. It’s emerged when Mr. Morley, the harp maker, who’s Clyde Morley, who still had a business, told me that there was still somebody with the name Harnack around.

And he said, I believe she lives in Bochner. Well, I now live in Sussex, so they’re either hotfooting over to Bochner to meet her. And she had all the Russians that London has had, the way she talked. I instantly felt so I knew her. Then we forged a friendship. She was in her 90s at the time herself. And there’s point of this is that she said, yes, she hated, hated it. But on Saturday mornings, she used to go in to help this old chap. String the harps for her pocket money and she hated harps. Cause it was, it’s a tough job. You can imagine. Yeah. Young lady going into this dusty workshop with this rather, perhaps rather crappy old fellow

Hazel Baker: That’s right. And he worked with his brother. Didn’t he? Your grandfather?

Moira Bonnington: He did, his grandfather, his brother was a bit younger and he tried to carry on the business, but he was quite poorly and that’s when it all fizzled out. And there was nobody to take over because the two sons, Henry, who was called Harry and George were in the musical business, they were violinists or fiddlers as my cousin Queen he said, you never say violence. They play the fiddle. And they played the fiddle in London theatres.

And one of them played in a band called Hair William Morgan’s, blue Hungarian band.

Hazel Baker: That’s a mouthful.

Moira Bonnington: It is a mouthful. And according to all the records, they played at big smart London venues, and they also played for royalty and the aristocracy because you got to remember Queen Victoria came from a Germanic background and Hungarian band played this kind of Hungarian gypsy music.

They had harps in it and they had an instrument called a Cimbalom. Which is a hammer dulcimer. So imagine you take the top off a piano and you hammer it on the piano strings. And she loved apparently that she loved this kind of music, but this band went around and I have a picture of them somewhere of them in their blue uniforms, which they look like his ours. You can imagine, as soon as the first world war came along, they ditched those uniforms and went into must’ve being a child of the sixties. I thought if you re say it slowly, Hair William Morgan’s Blue Hungarian Band, it’s roughly the same as Sergeant Pepper’s Lonely.

Hazel Baker: Yep, I was thinking that as well! That’s absolutely fantastic, Moira. I mean, it’s just amazing journey that you’ve been on and you’ll get, you’re still continuing on that journey now reconnecting your family’s history, I think is absolutely fantastic. And thank you so much for sharing that with us today.

Moira Bonnington: Oh, it’s great. Thank you for getting in touch. It’s been enjoyable.

Hazel Baker: And if you’re finding yourself with a little bit of extra time on your hands, now we’d locked down 2.0 in session, then perhaps this will inspire you to research your own family history.

If you do have a couple of seconds, then a review is always appreciated. Either click the stars or you can click the stars and write a little, a word review. I do read them all. Thank you very much to everybody who has partaken in that so far, it’s been really great getting your feedback and being able to curate the content that you want.

And if you are out and about in London and having your daily exercise and see something interesting and historic, then why not post it on Twitter and tag us @guided_walks or on Instagram @walk_london. It’d be lovely to see what you’re up to. That’s all for now. We’ll see you next time.