Guest: Stuart Hibberd

Stuart Hibberd is the author of The first Crystal Palace Football Club 1861-1876 and co-author of three football histories; To the Palace for the Cup, The Centenary History of the Arthur Dunn Cup, and Tottenham Cakes and Bolton Pies! -The story of the 1901 FA Cup. He is graduate of Cardiff University where he studied History and Economics.

Crystal Palace Football Club: The Beginning

Today we’re setting our sights on something that merges sport, culture, and history in a fascinating way—Crystal Palace Football Club, an institution that was founded in 1861.

Joining me in the studio is Stuart Hibberd, author of The first Crystal Palace Football Club 1861-1876 and co-author of three football histories; To the Palace for the Cup, The Centenary History of the Arthur Dunn Cup, and Tottenham Cakes and Bolton Pies! -The story of the 1901 FA Cup.

Hello Stuart!

[00:01:56] Stuart Hibberd: Hello, Hazel.

[00:01:58] Hazel Baker: Hi. Now, sport, I must admit, isn’t one of my strengths in terms of knowledge, in terms of, and also specifically, history. I must say that I was in a girl’s football team and I broke my nose playing that, which is why I’m able to do this. I think, supposedly, maybe the first question that I have for you is, can you please maybe share, give us an overview of the original Crystal Palace Football Club that was founded in 1861, but also specifically maybe the context of early British football.

[00:02:32] Stuart Hibberd:

Yes, I can. Perhaps, so I’ll take you back into the park where you were, Hazel and the sports ground that you saw is where the athletics stadium is now. Was actually the second football ground in that particular park. It was used between 19 1895 and 1914 for the FA cups.

So that’s from a later period of football to the one we’re gonna talk about today. But that was where Tottenham won the FA Cup for the first time in 1901, and hence that’s the subject of a recent book that I’ve done with friends and colleagues on that particular Cup Final. So yes, we’ve got the more recent history, perhaps pre-First World War, where the FA Cup Final’s there.

But my book actually was looking at a period… Before that, when football was first organised in this country. So we’re back into the 1860s and the men who formed the club in 1861 were actually cricketers. They’d formed a cricket club in 1857. And this was an independent sports club that rented the.

Cricket ground inside Crystal Palace Park. Joseph Paxton had been responsible for the design of the 200-acre park, and if we remember Queen Victoria came to the Crystal Palace in South London in June 1854. Then she opened the building, the famous building on the top of the hill, but then she had to return in June 1857, two years later, because it took longer to complete the landscaping layout of the park.

So she returned in 1856 and the cricket ground then opened and it was one of the main sort of sporting attractions at the time. The football club was founded in 1861 and We’re in prehistoric football times almost, in the sense that the Football Association wasn’t founded until two years later. This particular club only existed for a short period of time, it ceased to exist in 1876, but its short history coincides with the foundation of the Football Association, and they also participated FA Cup.

They’re one of a group of clubs that form the Football Association. The Football Association at this time wasn’t a national organisation, it was just one based of a few clubs in and around London. And the other claim to fame is that they provided football for the very first international games against Scotland.

And we just last night had the football match between Scotland and England, which was a celebration of the sort of 150th anniversary of the first game, which… actually took place in Glasgow in November 1872. I’d probably just want to give a quote to you of another football historian who said in his book, Terry Morris, Vain Games of no value, A Social History of association football in Britain during its First Long Century.

He concluded that football in the 19th century was essentially a collection of local histories, each with its own angles, characteristics and peculiarities. And the history of the club we’re going to talk about is one of those sort of local histories, but it also converges with the national foundations of the game.

The formation of the Football Association and the pioneering comp their pioneering competition, which was the FA Cup. And also, we want to point out, perhaps it’s one of the very earliest football clubs. Martin Wesby, he’s produced an excellent book on the chronology of early rugby and football clubs. And he has this club, the Crystal Palace Club, just the fourth formed in London and the eighth in the whole of England.

Sheffield being the oldest club, 18 dating back to 1857. So we’re talking,

[00:06:10] Hazel Baker: as you said, about before it really gets organised. And it’s not that long a history really, if you think about, I’m talking about Victorians, and now it’s such a huge industry, and with so many rules, as I’ve recently found out. If we’re going back to the club then, how did the club’s association with the Crystal Palace Exhibition Centre influence its formation in those early years?

[00:06:35] Stuart Hibberd: I’m not sure it did really, in the sense that the Crystal Palace Company was running a multi million, what is the equivalent today of a multi million pound operation, and taking in, there was hundreds of thousands of visitors who used to come every year to the Crystal Palace. A small football club with only playing two or three times a year maybe more.

on the cricket field in the early 1860s were really of no significance or interest at all to their business. Plus the fact we mustn’t see football in the 1860s obviously through the prism of modern eyes. It was very much in its early stages. It was an obscure pastime, just a winter pastime that Public school boys, which people have been at public school, took part in the winter, probably, in order to keep fit.

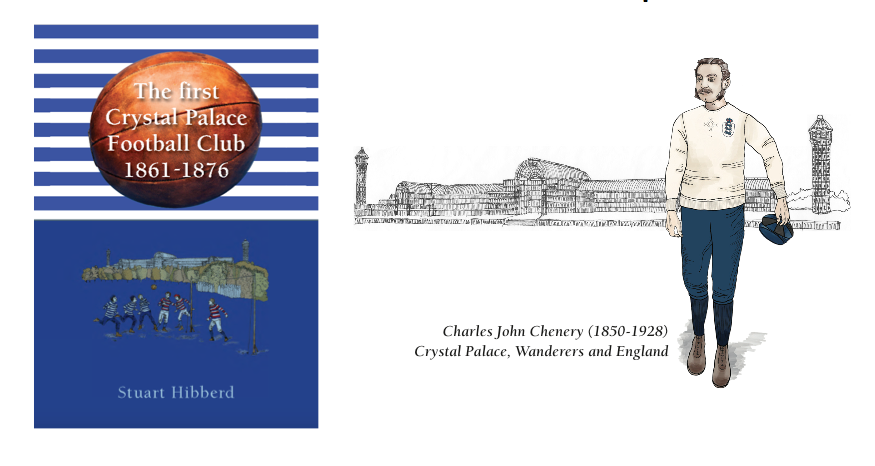

And I think a lot of these men, including Chenery, who was the most famous man who played for this club, would probably, in the first instance, regard themselves as cricketers, not footballers. Footballers was something they also did. And the other thing I would point out in this link with the Crystal Palace and the Crystal Palace site is that this club didn’t solely play at the Crystal Palace.

They, it would give them kudos, lots of kudos playing there because of how famous the Crystal Palace was. But they also played for two seasons down the road in Penge, behind a the pub called the Crooked Billet, and they were homeless for a couple of seasons in the 1860s. So there was a link to the Crystal Palace Park, but it wasn’t a solid link for the whole of their history.

[00:08:02] Hazel Baker: And that’s something we think now, don’t we, is that each football club has their own stadium and that’s their

[00:08:06] Stuart Hibberd: home. Yes, and also a thing of the time is that They would play for lots of different clubs, so you’d get an invitation, would you like to come and play for our club on Saturday? And you’d say, oh yes, I’ll come and play for your club.

So we find Chenry, the most famous player, playing also for Wanderers, another famous club at the time, and guesting in, in, in Chatham and other places during his football career. Can you

[00:08:29] Hazel Baker: talk about some of the rules and playing styles that the club then had to adhere to? How different are they to the rules that we have now, which are of course ever changing?

[00:08:39] Stuart Hibberd: I think that in, in a lot of respects they were totally different. It would look quite different to the modern eyes, a game of football from the 1860s. I think it’d be more akin if you think about when young children, five or six year olds first learn to play football or play a game of football.

They all run after the ball, don’t they? And that’s what we might have seen in the 1860s, a kick and rush style. Dribbling was important, because if you go back to the early football annuals, they talk about how good of a dribbler the player was. And when it first started in 1863, the first set of rules said that there was no forward passing, so you had to stay behind the ball.

And what you would do is run along with the ball dribble and people would be on either side of you to try and back up the attack as you try to move the ball down the field. So it’d look quite different. By the 1870s, because of the changes in the offside rule and perhaps the influence of the way they were playing against Scotland, it became a more open game and people spread out more over the pitch because the offside rule allowed people to pass forward, provided you didn’t, the players didn’t stand in an offside position.

It would look quite different, and as I say, in the 1860s, 1870s, early 1870s, they’d be playing with eight or nine forwards, which is unheard of today. Often today, you might just have a lone striker or two forwards, so it would look quite different. The first meetings of the Football Association in the autumn 1863, they were largely taken up with drafting and discussing what the rules would be.

And once a set of rules were determined, they went out into Battersea Park and played the first set game between two Football Association sides under the new rules. And if you go to Battersea Park, you can find a plaque which was erected by Wandsworth Council to commemorate that particular game. Sadly, they got the date wrong.

It’s one week out. But Huh. We won’t go about that, will we? No. The first actual game that was played between clubs under the new rules actually did involve the Crystal Palace, and they played, when they played, went to Barnes to play in February 1864. But the 1863 rules weren’t suddenly universally accepted all over England and Scotland.

No. No? The public schools had their own rules, and they played football under their rules. Sheffield was another important centre of football in the 1860s, and football was growing up in Sheffield. Sheffield had their own rules, slightly different to London rules. So when Sheffield and London played each other, they would perhaps play, if it was in London, they’d play under London rules, if in Sheffield in the Sheffield rules.

In some games they actually said, we’ll play one half under our rules and we’ll play one another half under your rules. So when football first started, the goals, there was no crossbar. You could kick it between the two posts at whatever height you wished, but they decided that was not really what we wanted.

Eventually they, they strung a tape between the two posts at a height of eight feet and provided the ball went below the tape. That was a goal, but the tape in Sheffield was higher than it was in London. It was nine feet high in Sheffield and eight feet high in London. But as football developed later on, we came to be a uniform eight feet and the dimensions of the goal, goals do actually go back to early football and the width, the eight yards is back to the London rules and the eight feet is London rules.

The touchline. Now we’ve got the touchline along the edge of the pitch. Why is it called the touchline? Again, we go back to the early rules, the 1860s. Under London rules, if the ball went out of play, the first player to touch it could take the throw in. The touchline. Sheffield had a different rule. It was the team that kicked it out.

didn’t get the throwing. The other team got the throwing like we do today. So again, we have three different rules. We have Sheffield’s rules, kicking the ball in any direction. London, you had to put it in by, at a right angle. Another feature was handling. Rugby, rugby and football came from the same roots really, and rugby has become a handling game and football has become a game for kicking the ball with the feet.

But to start with, football still had handling. You could still handle the ball in some way up to about 1870 when they outlawed it. But if you think in rugby, sometimes if you watch rugby where they kick the ball up in the air and one of the players catches and they do something called making a mark.

Making a mark was something that was still in football in 1863. Derives from both games started off with that. So we had the rules developing and d developing different parts of Britain, Sheffield, London, Scotland. But gradually they become they come together over time. And there was something called the International Football Association Board.

This was founded in 1882 in order to standardize the rules. And now we have FIFA really controlling that. And so we all play to the same people, play to the same rules. And

[00:13:36] Hazel Baker: what about the length? of a match and also the number of players. Has that always been the same or has that changed?

[00:13:44] Stuart Hibberd: In early days, sometimes the teams would decide between themselves how many players we’ll have often.

It’s by negotiation and if one team had more players than the other, one might, you quite often see players being lent to the other side. Some early games with 15 aside, early football games with 15 aside. And the length of the game, yeah, I think that goes back. to early times. But the other thing about the COF, to start with, every time you scored a goal, you would change ends under the London rules.

But eventually they only changed ends at half time, so that changed as well. And what about

[00:14:17] Hazel Baker: the size of a pitch? Because when did that standardization

[00:14:20] Stuart Hibberd: kick in? Again, that was something that was, I think, probably going, came in 1870s, 1880s, I’d have to check it, but I know that dimensions were a lot bigger than London at one point, even up to 200 yards in length.

So that was an enormous length of pitch, but it’s come down to dimensions now. I recently

[00:14:40] Hazel Baker: saw a video on TikTok of three professional Japanese footballers playing against 100 kids. And I had no idea when you were talking about basically a free for all. That’s what I’ve got in my head now. And it just sounds absolutely exhausting being always on trying to get the ball rather than actually working a little bit more strategically like our players do now.

So if we’re looking at roles and how, you mentioned about the Football Association, so what role did Crystal Palace Club play in that formation of the Football Association?

[00:15:21] Stuart Hibberd: They were back there at the start when the sort of the eleven clubs from around London met to, 1863, they had about half a dozen meetings or more leading up to the agreement.

of the rules. And there was two actual crucial meetings in November, on 24th November, December the 1st. And at that, at those meetings, it was decided that running and carrying the ball wasn’t permitted. So it wasn’t going to be a purely handling game. And also hacking was disallowed, because hacking was where you could kick the other player, perhaps on the shins or whatever.

Somebody, I think, pointed out that some people got to go to work on Monday mornings and we don’t. really want them being injured so they can’t get to work. The other thing I point out about the formation of the F. A. I think the stereotypical image of somebody who an F. A. committee man is somebody old, pale and stale and set in his ways.

Somebody like me, perhaps, but that wasn’t the case in 1863. In 1863, the oldest man at the first FA meeting was only 32 years old. There was actually a school boy from Charterhouse attended to the first FA meeting. He was only 19, and Francis Day, one of the main representatives from Crystal Palace Football Club, was 25 years old.

So these were young men who were playing football and finding their way in what was a new sport. How very

[00:16:44] Hazel Baker: exciting. I didn’t know about the Charterhouse, so that’s a good one to add to a little bit of trivia when I’m out that area. Now, would you describe the original Crystal Palace team as a pioneering force in early

[00:16:59] Stuart Hibberd: football?

Yeah, yes, I would, but I wouldn’t want to overstate it was one of a number of clubs that was trying to move football forward in the 1860s. And it wasn’t, it was a bumpy ride. We’ve got this organisation forming in 1863. At the start of 1864, we’ve got a man writing a letter to the papers saying, who are these people who think they can tell us how to play football?

We can get along fine without them, and it’s bound to fail. Again, it wasn’t a bump, it was a bumpy ride, because by 1868, there was even a suggestion that the Football Association might cease to exist, and it was down to certainly just 10 clubs. But it did turn the corner. Sheffield helped turn that corner, I think. Eventually we’ll see that the FA Cup helped expand the popularity of the game until something that became very popular by the 1880s and 1890s. And

[00:17:51] Hazel Baker: you’ve mentioned a few names already, but can you shed a little bit of light on some of the key players and also personalities with the club’s existence?

[00:18:00] Stuart Hibberd: Yes, I’d love to, because this is probably one of the most interesting areas of research for my book and I really enjoyed looking at the players and their biographies. And I would just say, if you want to experience the kindness of strangers, you send them a random email and say you’re writing a book about football, I think you’ve probably related to this person, can you help me?

And I had great kindness from strangers. I remember particularly, The member of the Allport family, Douglas Allport was one of the men who went out to buy the first FA Cup. Member of the Allport family photocopied 60 or 70 pages of their family history and sent it to me. Very kind. So who are these people?

Who are these men? They were middle class and upper middle class men. It wasn’t a working class game in the 1860s and 70s. As I’ve said before, these direct public school boys come back to London and they want to continue playing some form of sport in the winter. So they play, they look to football. And we know that they came from very wealthy families because we can trace their sort of family histories through the census returns and because they were middle class or upper middle class, they often leave a good historical footprint, for instance.

Whereas my great grandfather’s working in the potteries, there’s very little about him. He’s a working class man. They don’t leave much of a footprint. Or they die, sadly. So who’ve we got? We’ve got men of commerce. The boric’s baking powder. boric’s baking powder? There was a dissem No. One of the early Borics played for them.

There was four different Lloyd brothers from the Lloyd’s banking family, so very rich people. Two Neams, Shepard and Neam. brook Brewer is down the front. Yep. Two personality preps, so there was four guys who played football for England, who were Crystal Palace players, and there was 12 other. England players I identified who played at some point in as guests, perhaps of crystal palaces, but they played for the Crystal Palace, including Topher Ottawa Ottaway, who was the first ever England pent team.

Douglas Sa Porter mentioned he was a keen man for this club. He was on a three-man subcommittee who was tasked with the job of going out and buying the first FA cup. He was the crystal palace’s club secretary and captain for quite a number of years. Another man we came across, I’ve come across in the researches, was William Broderick Cloette.

He was a very wealthy South African, and he went on to have business interests in Mexico and the USA. He was an owner, a breeder of racehorses. His horse won the Oaks in 1911, and sadly he died on Lusitania. In 19, I think it was 1915, wasn’t it, when that sank. Walter Dorling, let’s introduce you to Walter Dorling.

He was the son of Henry Dorling and Elizabeth now, Henry was a widower and he had four children. He marries Elizabeth, who was also who’d lost her husband, a family friend. So the two of them get married and they brought four children to the marriage. So what do you do when you’ve got… eight children.

You go out and have another 13 children. We have 21 children in this family. And Walter, the one of the, one of the children from the, from this marriage, played football for Crystal Palace. Now, you’ve got logistic problems when you’ve got 21 children. So Henry was actually the clerk of Epsom Racecourse, an important post, Epsom.

The home of the Derby, he was the clerk of the course. Connect to the story, you can find Charles Dickens going down to see Henry Dawling. The logistics of all the children, that they overflowed out of the house, and so they used the grandstand when there was no races on as the nursery, which was also Henry’s workplace.

And at one point, Henry says, Elizabeth, what is this dreadful, awful noise? How can I, how do you expect me to do any work? And Elizabeth, his wife, said to him, Henry, that is your children and my children fighting our children. Walt’s darling is also of interest because Elizabeth is, Elizabeth was called Mason.

Now her daughter was Isabella Mason. Who we all know, because Isabella married a Mr. Beaton. So we’ve got Walter Dorling, Crystal Palace Footballer’s stepsister, is Mrs. Beaton.

Mrs. Beaton. Oh, fantastic how it Mrs. Beaton’s book of household management actually came out in 1861, on the same year as the Crystal Palace Football Club were founded. Again we probably think of Mrs. Beaton as a very old lady, don’t you, a sort of middle aged lady. But that wasn’t the case, very sadly.

Perhaps you know she died at the age of just 28, didn’t she? No age at all. Oh, in 1865. And she’s actually buried in West Norwood, is where you and I met, just behind where you and I met at History Fair.

[00:22:56] Hazel Baker: That’s right, I did know that because I went to a talk.

[00:23:01] Stuart Hibberd: Beaton actually in the fall of 1866 actually produced one of the very first books on football called Beaton’s Football.

So he published in lots of different sort of fields. Ah. Another person I want to introduce you to is George Rutland Barrington Fleet. Now he was a Crystal Palace footballer, and he mentions playing football with Crystal Palace in one of his two autobiographies. But his primary claim to fame is actually as a very early member of the D’Oyly Carte Opera Company.

Gilbert and Sullivan. And he was very famous in his day as the sergeant and the police in parts of penance and playing Poo bar in the ard. And he was also the racing correspondent for the punch. So he was quite a character and he was brought in nearby pen and played for football club. Wow.

And one, one last person I’ll mention to you is, there’s lots of others, but I’ll mention Frank Luscomb, Francis Luscomb. Now he predominantly was a rugby player. He was he did, but he also played football a few times to go to this Crystal Palace Football Club. He was capped six times for England between 1872 and 76, and was twice the captain of England’s rugby team.

The family lived locally, they lived in Forest Hill by the time he was playing rugby, but they previously lived very close to the Crystal Palace in Upper Norwood. His father is, was a ship owner called John Henry Luscombe. And he’s got an interesting history on his own because he was a ship’s captain. He went out and helped found Perth.

He was one of the first people who went out into Perth in the 1820s on the Swan River. But what came out of me doing the research was that John Henry Luscombe’s and Frank’s mother, Clara, kept a diary. And this has never been published, and that’s my latest project, annotating her diary. And she talks about going to the opening of the Crystal Palace in 1854, because the local doctor got her a ticket.

And what, and she tells, she talks in the diary, what a good seat she had. She was right at the front and could have seen Queen Victoria. Oh,

[00:25:02] Hazel Baker: fantastic. Oh, wow. Oh, I’m looking forward to that. So we’ve had a little preview there then, haven’t we? I’m lucky. You mentioned about the club participating in the first ever FA Cup competition, the 1871 72.

What about the significance there? How did the tournament, how was it received at the time? What was going on?

[00:25:27] Stuart Hibberd: It got off perhaps to a low key start. It was the idea of Alcock Charles Alcock, who was the secretary of the FA, and there had been successful, there’d been a football competition, a cup competition for that.

There was a couple that had been run up in Sheffield, and he probably also was aware of one that had taken, that the, there was, he went to Harrow, and Harrow had a cup competition. It went, it got off to a sort of a slow start, perhaps. There was 50 teams in the FA, 50 clubs at that time, but only 15 decided to take part.

But that included actually the Queen’s Park Club, who were the leading club in Scotland, and they still exist. The competition took place, Crystal Palace managed to get, reach the first the semi finals in the first competition, and then were knocked out by the Royal Engineers after a replay. The final, however, did attract 2, 000 people to the Oval, and they paid five shillings to see the game, which five shillings is quite a lot of money in those days, yeah.

And in foreign competitions, there was a rule that every game after the second round had to be played at the Oval. So they were cottoning on to, there was money in football, and that was perhaps a source of income to the Football Association. The FA Cup quickly expanded over the years, by 1877 78. There was 43 clubs that took part, including now Northern Working Class teams.

It was spread into the working class. Darwin FC entered then. And then there was 62 teams by 1881, and it was becoming more then as a national competition. And perhaps 1881 82 can be seen as a turning point, because that was the last time one of the southern amateur teams, when the old Carthusians beat the old Etonians.

But the FA club was a special thing for the game. In extending its interest across the country, it caught, I think, caught the public’s imagination.

[00:27:17] Hazel Baker: On what way did the social and economic conditions of the era impact the clubs then and its players if they’re becoming more mixed?

[00:27:25] Stuart Hibberd: Yes, to a large extent, I think that the Crystal Palace players and a lot of the London club players were from very, as I said, from very wealthy backgrounds and they were largely protected from the economic.

conditions of the day. They were led privileged lives and supported by servants. The 11 servants. The Chennerys had three. You can pick that up from the 1871 census, so look at the players lives there. And our great grandfathers and great grandfathers wouldn’t probably, if they were working class, wouldn’t be playing football because they had to work six days a week to support their families.

So the working class didn’t have Saturday afternoons off and they didn’t have the leisure time to play football. We didn’t get bank holidays introduced at all in this country until I think in 1871, the Bank Holiday Act. And also there was snobbery in class divisions, I think, obviously in Victorian society, we know that from Dickens and studying the period.

In 1872, 60 members of the London Athletics Club resigned. They didn’t want to be part of their club anymore because the club decided to admit tradesmen. Oh, no! Yes. And some of the Crystal Palace footballers were actually also members of the London Athletics Club. I think, there’s certainly reports of snobbery.

For example, in the first ever Football International, there was one chap from Sheffield and all the rest were Londoners. And the London people ostracised the shit guy from Sheffield.

[00:28:50] Hazel Baker: We know the club… Dissolved in 1876, but how did that all come about?

[00:28:56] Stuart Hibberd: It’s not, there’s not a terrible lot of documentation on that, so that was diff difficult for us to be absolutely certain, but it appears to be the lot of the ground.

They didn’t have a ground to play on. There was some sort of falling out with the Crystal Palace Company or perhaps the Cricket Club. because there was an attempt to revive the club in 1883 and in the newspaper report of this attempted revival it stated that the club had been disbanded following a misunderstanding with the Crystal Palace Club.

So what that misunderstanding is, I don’t, we don’t exactly know, but you can tell from looking at the fixtures and the games they did play, that they never played at the Crystal Palace after January 1875. So we’ve got whole year, really, where they didn’t have a home ground. So that would have contributed to the situation that not having a home ground, that diminishes the action of playing for a club if you’ve always got to travel away.

There was a game arranged in 76 and that was canceled and we, that was documented that, that was because the crystal palaces couldn’t, at that point raise a team. I’ve discussed this with a friend of mine who, who also has written a book on the set subject of Crystal Palaces Football Club. Gordon Law.

He’s the editor of the homedale net of. Crystal Palace found a website and he, I think we think that possibly Douglas Allport was a very important guy in the club. He retires and that perhaps left also a vacuum in the leaderships. There wasn’t somebody who came after him who’s strong enough to take the club forward.

And that often happens with small sports clubs or sports teams is that they’re very reliant on one or two people doing all the jobs, even today. If that one or two people disappear or move away. And it’s that’s danger of the team folding or club folding.

[00:30:43] Hazel Baker: And we know there’s a distinction between the original Crystal Palace Football Club and the current one, but what are the historical connections, if any?

[00:30:53] Stuart Hibberd: There aren’t any really. The two clubs aren’t connected. The 1861 club, as we have mentioned, folded in 1876 and disappears from the records and ceases to exist.

So there was nearly 30 years before A professional club started up with the help of the Crystal Palace Company in 1905, so the two clubs aren’t connected.

[00:31:14] Hazel Baker: And when you’re researching, what were the myths or misconceptions about the original crystal palace that you thought ‘I need to clarify this’?

[00:31:25] Stuart Hibberd:

There was one that you will find in sort of corners of the internet still, you’ll find pictures of some navvies set outside the Crystal Palace, and it will say underneath the purse. The Crystal Palace Football Club was founded by workers at the Crystal Palace, which it wasn’t founded. People who played for the Football Club were workers at the Crystal Palace.

They were stockbrokers, they were trainees, solicitors, they were in professions where they weren’t, so that’s a complete myth. When you find this on the internet, and you find it in old football books as well, there would be a picture of these navvies. But the navvies had finished when the park had finished being landscaped in 1856.

They didn’t sit around in the park for six years waiting to form a football club, the navvies. They went off and… They went off and When the job’s done, they go off to get the next one. They went off to build the railway lines and that’s a myth that’s now been solved, a myth that’s gone away really, I think because of the research people have done.

[00:32:19] Hazel Baker: And for anybody interested in exploring more about the original Crystal Palace Football Club, what sources would you

[00:32:27] Stuart Hibberd: recommend? The Victorian newspapers a fabulous resource really, and membership subscription. The British newspaper libraries is a great source of old football reports because there were lot, there were different football periodicals, football newspapers, sports papers that the Victorians published, and they’re full of accounts of these particular games, and they’re invaluable.

for somebody looking at sport in the 1860s and 1870s, so they’re very good. And you can also, you could also join the Welcome Foundation Library and gain online access to Victorian newspaper and period articles. I’ll just say, you mentioned one. The books that I’ve been involved in early on, it’s so much different to the struggle we had putting together a book in the 1890s, in the 1990s on football at the Crystal Palace where we had to go up to Collindale Library, have a day off work, ask for a man or a lady to bring out some newspaper and then perhaps do a copy of it.

It was so difficult. Computers and digitalization has been a godsend, hasn’t it, to historical research.

[00:33:28] Hazel Baker: Yeah, agreed. What about any records or memorabilia that are from the original club? Is there anything that exists now?

[00:33:36] Stuart Hibberd: I think at the moment we’ve only, there’s only been discovered a single artefact and that’s a glass bottom tankard and that related to a Crystal Palace football club competition that took place in 1873 74 and the tankard was actually sold at auction in America 1, 250 in 2014.

Other things that might be of physical interest are, there was a couple, we talked about Frank Luskin, his father, the ship owner. I don’t know if I mentioned, he actually, he did go out as a ship’s the ship owner, he was the owner of convict ships. Oh, I did not know that. Including the penultimate convict ship that went to Australia.

So he’s got an interesting… shipping history. Anyway, going back to Frank, he won an athletics event at Crystal Palace in 1869, and that particular cup is on display at the Crystal Palace Museum, which is at the top of Annerley Hill in Upper Norwood, if you want to look at that. I think the museum is just open mainly on Sunday afternoons.

We’ve got to a period when the middle classes, upper middle classes, are going to photographic studios, having their photo taken, producing carte de visites. Those, we still have those. And families have still got photographs of their family members from those days. I found some that had never been published before and used those in my book.

One of my favourites was, which comes from University College Oxford, and at University College Oxford they’ve got the Arnold Kierkegaard Smith Collection. Now, Arnold Kierkegaard Smith was the first England goalkeeper. in 1872, in the match that was played in Glasgow in 1872. He, the, his photos, photographic collection is at Oxford, went up there and just, I put in the book I don’t think it had ever been published before, the photograph, all the people knew of its existence, was the first photograph with more than one England footballer in the same photograph shows, I think, four ladies and six gentlemen.

before the Oxford commemoration of May 1873. So it’s a party at Oxford. So they’re all sat there dressed in their best finery with their top hats on and the ladies with wonderful dresses, and that’s a wonderful photograph. And Chenry, one of the Crystal Palace footballers, the man who got three caps for England, he’s in that photograph.

So it’s a marvellous photograph. I researched who else was at the Oxford commemoration in May 1873. Alice Little. Alice in Wonderland. She was a party, so that’s rather good. You can get postcards of George Rutland Barrington Flea, the man I mentioned who was the Dolly Cart singer, so you can find those out there as well.

And my most important probably find wasn’t, I didn’t find it, it fell into my lap. was Charles John Chenery’s Diary. Mentioned Charles John Chenery, first man to get three caps for England. He played in the first three football, ever football internationals. I’d nearly finished the book, and I got an email to say, with a phone number to say, would you be interested in Charles John Chenery’s Diary?

And I said, Yes, I would. Fantastic. What a fantastic thing. He kept a diary between January 1874 and June 1875. How did somebody out of the blue contact me to say, Are you interested in the diary? As part of my research, I tried all sorts of sources, and Chenery eventually goes out to Australia, where his family had a sheep farm in Australia.

So I was in contact with the local history society near the sheep farm and said, have you got anything on the Chenry family? And they said, no, sorry, not really. The person with the diary, four years later, goes, contacts the same history society and say, I’ve got this diary, are you interested? And they say, oh, yes, that is interesting.

Some bloke in England contacted us four years ago. He might be interested. I have the Mansfield Historical Society, which is 60 miles north of Melbourne. They put me in touch with a man whose wife was Chenery’s great granddaughter, who probably lives about 20 miles, no less, about 10 miles from me.

Whoa. That’s wonderful. Chen’s diary is great ’cause he includes a description of him going up to play for England against Scotland in 1874. And maybe I. Maybe I should read a bit of it, or… Oh yes, please. Okay, so we’re in 1874, this is the Third International, March 1874. So Chenery’s been picked to go and play for them.

He’s also a very good cricketer, so the diary’s wonderful because it covers a couple of summers and where he’s playing cricket and… But when does he go up to school? He actually goes up on Wednesday evening. He leaves King’s Cross on Wednesday evening at 9. 15. And he’s lucky to have his carriage almost to himself up to Darlington, but he says he hardly slept.

But the engine then breaks down outside Berwick. There’s no change here, is there, Simon? He eventually gets into, but he stays in Edinburgh, because Edinburgh, I think, because Edinburgh’s got friends there and it’s more fashionable. So he lunches with friends, goes to a painting exhibition, and then he goes dancing, and Chenry loves dancing.

This is Thursday night, he doesn’t get home till four o’clock in the morning, Friday morning. Not great preparation for his football match. Then what, so what does he do on the Friday? He meets some girls, goes for a walk with them, and then in the evening, what does he do? He goes to another dance. He tells us it’s a really good dance, not a bad dancer in the room, and everything done is…

First in first rate style home 4 to 45 a. m. So the night before the match he’s been up to 4. 45 a. m. The day of the match up at 10 o’clock went for a walk along the Dean Road with Mary and then by the one o’clock. train from Edinburgh to Glasgow, met the fellows, that’s his teammates, at the George, which is in George Square in the centre of Glasgow, and went to Partick to play football England v Scotland.

More presence than I’ve ever seen at a football match before. The Scotsman estimated the crowd to be 10, 000 people, so it was a very big crowd. Although other estimates might, maybe 7, 000. Anyway, dined in the evening a very good dinner, not so many men fow. F O W. I had to research what does fow mean. It meant there’s a slang word from the time for drunk, not with many drunkers, or last time, which would be the 1872 game.

Went to bed at 2. 15. See that was his earliest night in Scotland.

[00:40:28] Hazel Baker: Please tell me he was in his 20s.

[00:40:29] Stuart Hibberd: He was in his 20s. He was 24 because he was born on New Year’s Day 1850, 1850. So he would be 23, 24 at this time, 24 at this time. Yeah, so badly behaved footballer. So there’s nothing new in the world, is there really?

[00:40:48] Hazel Baker: All he was missing was the wag. Now you’ve mentioned a number of sports already, but what other sports were being played at Crystal Palace at that period as well? What else was going on?

[00:40:58] Stuart Hibberd: Yeah, cricket was important there, their own cricket club and that was a very strong social thing as well. They had a very strong fixture list against all the other good cricket sides of the time.

And Kent there played once or twice. The Surrey-Kent border actually goes straight through the middle of Crystal Palace Park next to the cricket grounds. You could probably hit a ball. out of Kent into Surrey if you were playing cricket there on the cricket field. Cricket was a big thing and the cricket side stayed there until 1900 when it was replaced by WG Grace’s side, the London County Cricket Club.

Athletics, athletics was a big thing for in Victorian England. There were lots of athletics meetings, local sports club held their meetings there, and businesses from the city would bring their people down for the day and have a sports day down there. In August 1866, they held an athletics event, and it was midweek.

Even though it was midweek, the 10, 000 people turned up. One of the people who was competing was a young 18 year old W. G. Grace. He won the 440 yards hurdle race in 70 seconds. But what was exceptional about Grace winning this race, he was actually in the middle of a cricket game. He was playing at the Oval.

And he had to ask the captain permission to… Leave and go down to the Crystal Palace to do some athletics and then he went back up to the Oval to continue playing for England and England 11 versus Surrey. The president of the Crystal Palace Athletics Club, they formed an athletics club, he was Thomas Hughes MP, who was Thomas Hughes, the author of Tom Brown’s Tool Days.

And a lot of members of the football club are also members of the Crystal Pines Athletic Club, including Douglas Allport, who we met. And I’d like to draw your attention to the case of Wheeler versus Hillier, 1873, heard at the Guild Hall in early 1873. Now, Mr. Wheeler… was a gentleman who’d been down to the Crystal Palace in 1872, and he took the, he entered the three mile open handicap race.

Before the race started, there was an objection saying he shouldn’t be in this race because he’s not a gentleman. But even though there was a bit of a sort of set to, he took part in the race, and he won it. And they wouldn’t give him his prize because of this objection that he was not a gentleman. So Wheeler took the secretary of the Crystal Palace Athletics Club to court.

And what was at stake was 10 worth of fish knives and forks, because I suppose a 10 prize was a lot of money in those days. Wiggler was, he was a tradesman, he worked for a removal company at the time, like Pickford’s, a removal company. He contested the fact that he won the race and he entered it on good…

Good faith. Good faith, yes. So he should have had the fish knives and forks. And the court actually found against him, and they said there was a question about whether he was an amateur, and I don’t think that was, I think that was accepted, perhaps he was an amateur, but it turned on the question of, was he a gentleman, and they decided he was not a gentleman, and the race…

Even though it was incorrectly listed as a race for amateurs, it should have said gentlemen amateurs. And the court found in favour of the Crystal Palace Athletics Club, which again probably shows perhaps the snobbery of the time or the class divisions of the time. And the strange thing, the other thing that connected to that is I found in the newspapers, shortly after the report of the case of Wheeler’s case and losing the case, is that the Sporting Gazette, which was one of those sporting papers of the day, publishes an article with three different tables in it.

Table, in table one, was a list of those athletics club and sports clubs, which were purely gentlemen’s clubs. Table two was clubs which had some gentlemen, but not wholly gentlemen. And table three was the president’s clubs. Gosh. The first-ever cycle races probably in Britain took place at the Crystal Palace.

They had Velocipede races in 1869. The first prize was a French Velocipede valued at 15. They’d been terribly uncomfortable to ride because they were made of wood and they had the wheels where the pedals were on the front wheel. So there were no chains in those days. So they’d been incredibly uncomfortable probably to ride.

So we had Velocipede racing. And people still cycle around and it’s got a long history, a cycling history of the Grissle Pass part up till today. Wow, goodness. Archery, archery was very popular in those days and there were two different places where you could do archery. Archery was so popular I think in the 1860s, and 1870s, There were eight different archery shops along Oxford Street, eight different places you could buy archery equipment, which I suspect there aren’t any at all today, but 1860s, and 1870s archery is incredibly popular.

[00:45:55] Hazel Baker: I suppose with archery, women were least able to partake in that one.

[00:45:59] Stuart Hibberd: Yes, that was one of the reasons, perhaps it’s popularity, it’s one of those things that could be, the two sexes could meet, and it was a social thing as well as the sport perhaps, and the same applied to croquet.

Croquet was played at the Crystal Palace and some of the Croquet championships. That’s just The formation of Wimbledon, I think Wimbledon dates back to 1877. There was a discussion about whether the championships would perhaps be at Crystal Palace, but, I think the Ten Authorities decided that they wanted their own space.

Swimming. Now, swimming is quite interesting because there was no swimming pool there in those days, but there was a lake, a boat, a boating lake, which was actually part of the fountain system. It was a reservoir, really, for the water. The Crystal Palace had a fabulous fountain system, which didn’t always work.

It was fabulous when it did work, and the water would go down the park to the bottom. and then be pumped back up to the top of the park, and there was a lake at the bottom where the dinosaurs are. That was used for the English One Mile Swimming Championships in 1875 and again in 1878, and the winner of the One Mile in both years was a Horace Davenport, and Horace was a contemporary of Captain Webb, who was the Channel.

But he was also the English Plunging Champion. What is plunging, Hazel? Do you know what plunging is?

[00:47:18] Hazel Baker: No. All I can really think of is something to do with plunge pools?!

[00:47:20] Stuart Hibberd: Okay, plunging is where you stand on a small box and you dive in and you see how far you go, but you mustn’t move your arms or legs, you just see how far you can go.

So you just float and glide. as far as possible and the person who glides the furthest is the winner. So Horace was the English plunging champion and he went 68, 64 feet 8 inches when he won it in 20 meters. It’s half a swimming pool now, isn’t it really? Goodness, yes! And plunging was actually in the 1904 Olympics.

It was a thing. It was a thing in Victorian times, plunging. Gosh. 1904 Olympics. And he was also a long-distance swimmer. He swam between South Sea, which is Portsmouth, and Ryde on the Isle of Wight, and he swam, it took five hours, 25 minutes. Can get over a lot quicker on the hovercraft today. I think so.

You’re not prior. Yes. So again, it’s a very rich sporting history. So it’s another book really, but I did do a chapter specifically on the 1860s and 70s sport part of the book, because I kept coming across these other sports. I thought that this is interesting. Let’s do something on that. There was even two baseball teams that came over to Crystal Palace as part of a tour of Britain.

North Britain and Ireland in 1874, they came over to convert us from cricket to baseball.

[00:48:46] Hazel Baker: I think that they were rather unsuccessful in that.

[00:48:48] Stuart Hibberd: Yeah, yes, they didn’t meet our objective, but the people who saw the games were very impressed with the baseball quality of their fielding. And there was a team from Boston, Philadelphia played at Crystal Palace, and one of the Boston side was called in partner Spalding family that produced tennis rackets, a sporting goods family.

[00:49:06] Hazel Baker: And for our listeners I’ll put all the links on the website as well so you can get Stuart’s book and you can also read the transcript as well which sometimes helps. And if you want to listen to a little bit more about Crystal Palace Park specifically, then you can listen to our episode 47, all about the Victorian dinosaurs there with one of the workers, Sarah Slaughter.

So all that’s left for me to do, Stuart, is thank you very much. Who knew there was so much unknown history about Crystal Palace Football Club? Thank you.

Stuart Hibberd: Thank you, Hazel.

Hazel Baker: That’s all we’ve got time for. Until next time.