Introduction

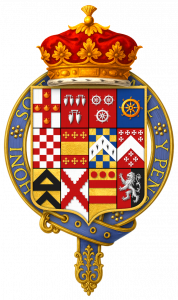

George Villiers, 2nd Duke of Buckingham: The Scandalous Life of Restoration London's Most Notorious Courtier

In the glittering world of Restoration London, no figure embodied the era’s excess, brilliance, and scandal quite like George Villiers, 2nd Duke of Buckingham (1628-1687). From his early years as Charles II’s childhood companion to his notorious love affairs and political machinations, Buckingham’s London life reads like the plot of a Restoration comedy; complete with duels, theatrical debuts, and a spectacular fall from grace that inspired one of English literature’s most famous satirical portraits.

Early Life: Raised in Royal Splendour

Born on 30 January 1628, George Villiers inherited his father’s titles when just seven months old following the 1st Duke of Buckingham’s assassination. This tragedy became his greatest advantage: King Charles I took responsibility for raising George alongside his own sons, the future Charles II and James II, in the royal household. This extraordinary upbringing forged bonds that would define Buckingham’s entire career, creating a friendship with Charles II that survived exile, restoration, and countless scandals.

During the Civil War, young Buckingham fought courageously for the Royalist cause, escaping the catastrophic Battle of Worcester in 1651 to rejoin Charles II in exile. When Charles was restored to the throne in 1660, Buckingham returned as one of his most trusted intimates, participating in the coronation procession and even carrying the orb at the ceremony.

The CABAL Years: Political Power and Influence

Buckingham’s political zenith came with his membership in the notorious CABAL ministry (1668-1674), where his initial spelled out part of the group’s name: Clifford, Arlington, Buckingham, Ashley, and Lauderdale. As one of Charles II’s inner circle, Buckingham wielded enormous influence over government policy, particularly in foreign affairs.

His political style was characteristically flamboyant. Contemporary sources describe him as brilliant but undisciplined, capable of great insight but prone to spectacular miscalculations. The CABAL years represented the height of his power, where he could make and break careers and shape the direction of Restoration England.

London Residences: From York House to Downing Street

York House: Magnificence and Financial Ruin

Buckingham’s most spectacular London residence was York House, the grand riverside mansion on the Strand inherited from his father. Originally built for medieval bishops, it had been transformed into one of London’s most magnificent private homes. Buckingham made it the centre of Restoration social and political life, hosting elaborate entertainments and using its strategic location near Whitehall for diplomatic purposes.

However, Buckingham’s extravagant lifestyle created crushing debts. By 1672, he was forced to sell York House to developers for £30,000—a massive sum that still couldn’t solve his financial problems. With characteristic vanity, he insisted the new streets commemorate his name and titles: George Street, Villiers Street, Duke Street, Of Alley, and Buckingham Street.

Downing Street: Power at the Heart of Government

Buckingham’s connection to Downing Street came through his residence in the grand mansion that would eventually become part of Number 10. When he joined the CABAL Ministry in 1671, he took possession of this property, spending considerable sums rebuilding and improving it. This residence perfectly suited his dual role as courtier and politician, providing both the grandeur expected of a duke and proximity to government necessary for his political activities.

The Shrewsbury Affair: London's Greatest Scandal

No episode better captures the theatrical drama of Buckingham’s London life than his affair with Anna Maria Talbot, Countess of Shrewsbury. This scandalous relationship dominated London society in the late 1660s and culminated in one of the most notorious duels of the Restoration period.

On 16 January 1668, Francis Talbot, Earl of Shrewsbury, challenged Buckingham to a duel at Barn Elms. Samuel Pepys recorded the event in vivid detail, noting that Shrewsbury was “run through the body, from the right breast through the shoulder” and died two months later. Legend claimed the Countess herself attended disguised as a boy, holding Buckingham’s horse.

The scandal deepened when Buckingham installed the widowed Countess in his own home alongside his wife Mary. This brazen ménage à trois shocked even jaded Restoration society. As Pepys acidly observed, “This will make the world think that the King hath good councillors about him, when the Duke of Buckingham, the greatest man about him, is a fellow of no more sobriety than to fight about a whore”.

Literary London: Playwright and Satirist

Buckingham’s involvement in London’s theatrical world added another dimension to his metropolitan life. He was not merely a patron but an active participant, writing plays performed at Drury Lane and Dorset Garden.

His most successful work was “The Rehearsal” (1671), a savage satire of contemporary dramatic conventions that specifically targeted poet laureate John Dryden. Performed at the Theatre Royal, the play became a sensation, establishing Buckingham’s reputation as a wit capable of destroying reputations with his pen.

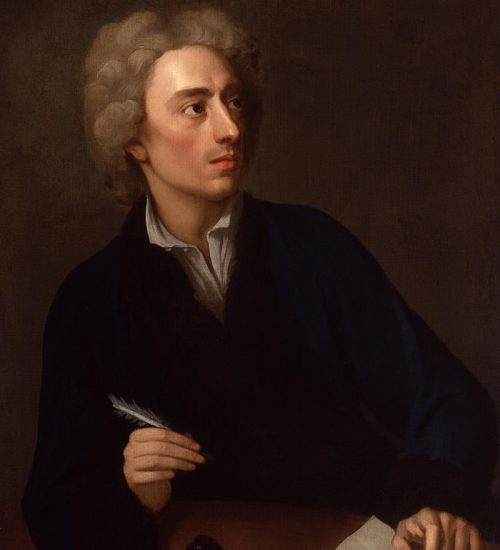

Alexander Pope's Literary Portrait: Death and Legacy

Buckingham’s death on 16 April 1687 at Kirkby Moorside in Yorkshire became the subject of one of English literature’s most famous satirical portraits. Alexander Pope, writing nearly fifty years later in his “Epistle to Dr. Arbuthnot” (1735), painted a devastating picture of the Duke’s end:

“In the worst inn’s worst room, with mat half-hung,

The floors of plaster, and the walls of dung,

On once a flock-bed, but repair’d with straw,

With tape-tied curtains, never meant to draw,

The George and Garter dangling from that bed

Where tawdry yellow strove with dirty red,

Great Villiers lies—alas! how chang’d from him,

That life of pleasure, and that soul of whim!”

However, Pope’s account was largely fabricated for dramatic effect. Contemporary evidence shows Buckingham died not in “the worst inn’s worst room” but in Buckingham House, described by J. Gibson of Welburn Hall as “the best house in Kirkby Moorside, which neither is nor ever was an alehouse”. Buckingham had been staying there during a hunting expedition when he caught a fatal chill.

The Real Relationship with Pope

Contrary to popular belief, Alexander Pope (1688-1744) and George Villiers, 2nd Duke of Buckingham (1628-1687) never actually met—Pope was born a year after Buckingham’s death. Pope’s famous lines about Buckingham were based on historical accounts and literary tradition rather than personal acquaintance. The satirical portrait in the “Epistle to Dr. Arbuthnot” was written to illustrate moral lessons about the vanity of worldly ambition rather than to record actual events.

Pope’s devastating verses helped cement Buckingham’s reputation as the archetypal Restoration rake, though modern historians note this literary portrait obscures a more complex figure who was also a patron of learning, a serious politician, and a talented writer.

Final Years and Death

By the mid-1670s, Buckingham’s political influence waned following his dismissal from the CABAL in 1674. Though briefly restored to favour in 1684, he never regained his former power. His final years were marked by financial difficulties and declining health.

Buckingham died on 16 April 1687 at Kirkby Moorside, Yorkshire, after catching a cold while fox hunting. Despite Pope’s dramatic verses about poverty and squalor, Buckingham died as a guest in the finest house in town, attended by servants and retaining his titles and some wealth to the end.

His body was returned to London and buried in Henry VII’s Chapel at Westminster Abbey. Unlike his father’s elaborate tomb, Buckingham’s grave remains unmarked—perhaps fitting for a man whose greatest monument was his scandalous reputation.

The Epitome of Restoration London

George Villiers, 2nd Duke of Buckingham embodied the contradictions and excesses of Restoration London like no other figure of his age. His life encompassed the highest levels of political power and the most notorious social scandals, the cultivation of learning and the pursuit of pleasure, genuine wit and destructive irresponsibility.

From the coffee houses and drawing rooms to the theatres and government offices, from the duelling grounds to the bedchambers of Restoration London, Buckingham left an indelible mark. His London life remains a fascinating case study in how personal relationships, political power, and cultural influence intersected during one of English history’s most dynamic periods.

Whether remembered through Alexander Pope’s satirical verses or through the streets that still bear his name, Buckingham’s legacy illuminates the glittering, dangerous world of Restoration London in all its splendour and excess. He was, as one contemporary noted, “the first gentleman of person and wit,” whose life of pleasure and soul of whim epitomised an age of remarkable freedom, creativity, and scandal.

🎧 Listen to London History Podcast Episode 139: Downing Street – A Microcosm of London and learn more about the former residents of Downing Street