In the winding labyrinth of London’s storied past, Kentish Town holds a rather peculiar legacy. Nestled in the heart of this vibrant neighbourhood, Angler’s Lane has been home to an array of businesses and industries, each adding a unique layer to its rich tapestry. But among these varied enterprises, one stood out for its uncommon nature: the false teeth factory.

It all began in the early 19th century, as the British Empire was reaching its zenith. With sugar imports surging from the colonies, the British population’s consumption rose dramatically, leading to widespread tooth decay. The demand for false teeth grew exponentially as society sought to address the dental fallout from this newfound sweet tooth.

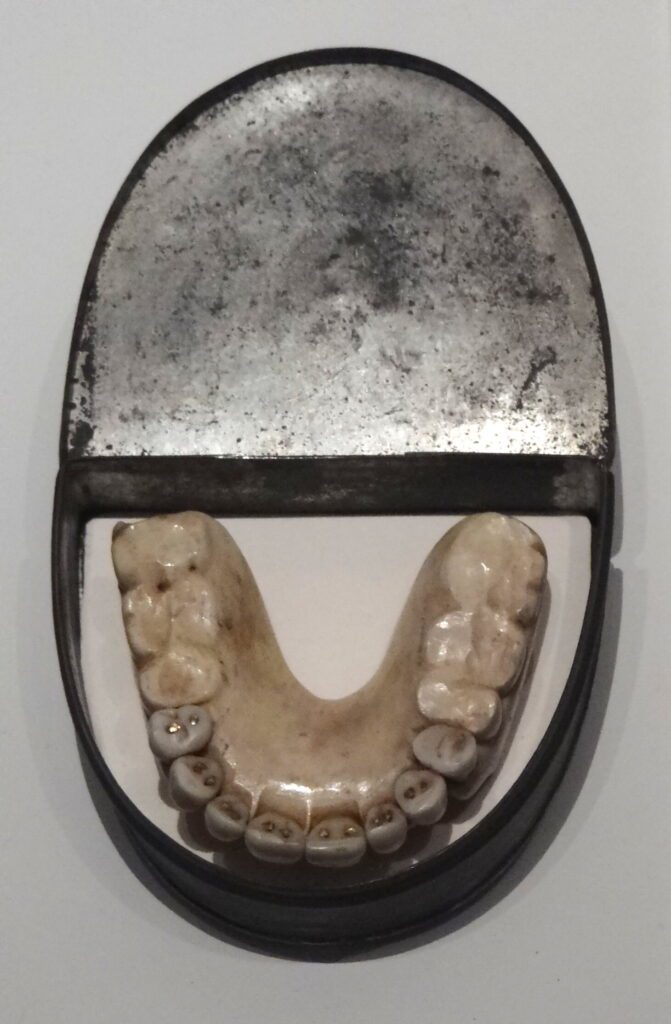

False teeth factory on Angler’s Lane

Cue the arrival of Claudius Ash & co, false teeth factory on Angler’s Lane, which turned Kentish Town into an unlikely hub of dental innovation. Set up in the 1850s, this factory was a sight to behold. It was in this nondescript building where skilled craftspeople melded art and science, crafting dentures that not only restored function but also ensured aesthetic appeal.

The premises consisted of the works consisting of fixed and loose machinery, warehouses, showrooms and offices. In 1905, an audit was taken and in it describes how the 125ft front of the premises was on Kentish Town Road. The frontage on Angler’s Lane was 281ft with a total area of 35,125 sq ft. Ground rents were £120 per annum. Some of the space had been leased out amounting to £642 per annum. The area of the works proper was about 18,900 square feet where substantial brick buildings equipped with special plant and machinery for the production of artificial teeth on a large scale and ‘dentists’ materials were housed.

At no. 205 Kentish Town Road was a leasehold shop, with a 5-year ground rent of £7 12s which had been sub-let for £140 per annum.

The warehouses, showrooms and offices were situated on Broad Street and Golden Square with a frontage of c. 365ft and occupied an area of about 11,342 sq feet. 8,534 sq ft was freehold with the remainder being leasehold with terms from 16-19yrs resulting in a rental income of £276 per annum. On Livonia Street, there were leasehold stables held for 40 years and 6 months at a rental of £54 per annum. The total value of Claudius Ash & co including freehold and leasehold works, properties, warehouses, showrooms, and offices together with the fixed plant, machinery and fittings, loose plant, tools, moulds, patterns and models was estimated to be £79, 582. This excluded stock-in-trade, patents and book debts.

The factory sourced teeth from a variety of interesting places. Teeth were often procured from human donors – usually individuals in dire financial straits or teeth extracted from the deceased. The Battle of Waterloo in 1815 even led to a grim supply of teeth that were salvaged from the fallen soldiers on the battlefield, leading to the term ‘Waterloo Teeth’.

However, as the ethical issues surrounding these practices became more apparent, the factory pivoted to using animal teeth and eventually developed porcelain teeth. The creation of porcelain teeth was indeed a game-changer, offering a more hygienic, ethically sound, and aesthetically pleasing alternative.

Dental Advances

Despite the success of the false teeth factory, by the turn of the 20th century, advances in dental care and oral hygiene practices saw a decline in the need for false teeth.

In 1907 Claudius Ash & Co began a new company called “The Platinum Corporation Ltd” designed to develop important concessions in the platinum-bearing district of Russia (the Ural Mountains) which has been the producer of 90 percent of the world’s platinum supply for nearly a century. The capital of the new company was £300,000.

Platinum was required due to its strength, resistance to corrosion, bio-compatibility, and excellent bonding properties. The use of platinum in denture construction represented an advancement in dental technology, improving the quality and longevity of false teeth.

One of the main uses of platinum in dentistry during this period was for making dental alloys, which were used as a base for false teeth. Platinum was mixed with other metals, such as gold and silver, to create a strong, durable material that could withstand the physical demands of chewing and talking and the corrosive environment inside the mouth.

The use of platinum had several advantages:

Durability and Strength: Platinum is an incredibly strong and durable metal. When used in denture construction, it provided a robust framework that could support porcelain or other materials used for the actual tooth replacement.

Corrosion Resistance: Platinum is highly resistant to corrosion, an important property for any material used in the mouth, where it is exposed to various fluids and food substances.

Bio-compatibility: Platinum is generally non-reactive and doesn’t cause adverse reactions in the body, making it a suitable material for use in dental prosthetics.

Bonding Properties: Platinum has excellent bonding properties, particularly with porcelain. This allowed dentists to create realistic-looking teeth. The platinum would be used to form a thin layer or “foil” onto which a layer of porcelain could be fused. The resulting prosthetic tooth would be both durable and aesthetically pleasing.

In 1918 there was a race to raise £100,000,000 for the war fund. They called it the Tank Campaign. Claudius Ash & Co donated £10,000 to the campaign by carrier pigeon.

In November 1924 Claudius Ash Sons and Co. Ltd bought De Trey and Co. Ltd, manufacturers of dental requisites. The final prices for De Trey shares were £1 3s 16d and for Claudius Ash 19s 9d.

The End of an Era

On 30th July 1931 Mr Henry Claudius As, who lived on Hamilton-terrace, Regent’s Park died at the age of 83. His estate was valued at £134,979 gross and a £134,513 net. He left a large number of bequests including £50 each to fourteen hospitals, including University College Hospital and the British Hospital for the Functional Mental and Nervous Diseases, 72 Camden Road. He also left £50 to St. Dunstan’s Hostel for Blinded Sailors and Soldiers.

By the 1930s, the factory on Angler’s Lane had closed its doors, leaving behind a fascinating legacy.

As we walk down Angler’s Lane today, amidst its bustling cafes, vibrant shops and charming residences, we carry with us the echoes of this past. A past that not only moulded the history of Kentish Town but also shaped the trajectory of dental care and innovation, leaving us with a captivating piece of London’s historical puzzle. So, next time you stroll down Angler’s Lane, take a moment to recall the unique legacy of the false teeth factory and the remarkable piece of history it adds to our beloved Kentish Town.