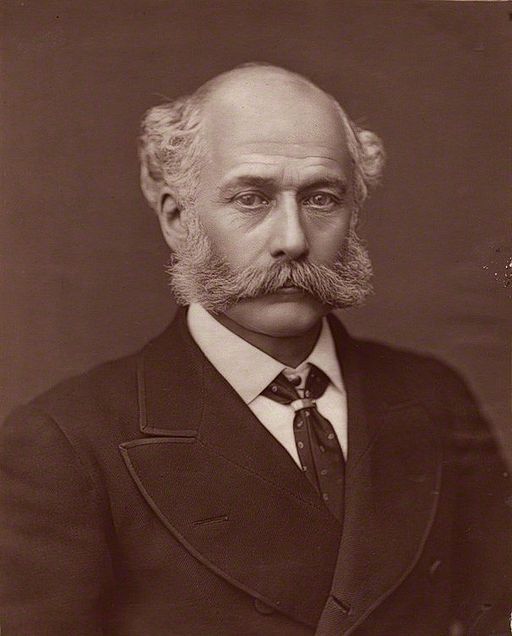

In the annals of history, few people have had as transformative an impact on a city as Joseph Bazalgette had on London. His name may not be as universally recognizable as other historical figures, but his contributions to public health and urban infrastructure are monumental, shaping the course of London’s history and laying the groundwork for modern urban planning.

This blog post delves into the life, career, and legacy of Sir Joseph Bazalgette, a visionary engineer who, during the Victorian era, transformed London’s sanitation system, combating disease, improving public health, and paving the way for the city’s future growth.

Early Life and Career of Joseph Bazalgette

Born into the city he would one day revolutionize, Joseph Bazalgette arrived into the world on March 28, 1819, in the heart of London. His heritage was deeply rooted in the resilience and resourcefulness of the French Huguenots, a Protestant group known for their industriousness, who had sought refuge in England from religious persecution in France.

Bazalgette’s educational journey was as diverse as it was comprehensive. His schooling spanned various institutions, embodying a rich tapestry of learning environments. One memorable episode of his educational journey included an immersive linguistic experience in Normandy, France. Here, he not only learned the intricacies of the French language but also absorbed the cultural subtleties of his ancestral homeland, which likely broadened his worldview and honed his problem-solving abilities.

Upon completion of his formal education, Bazalgette embarked on his professional journey in the engineering world. This path seemed a natural choice for a mind as analytically adept and rigorously trained as his. His first significant engagement was in the arena of railway engineering, a burgeoning field in the 19th century. Under the tutelage of luminaries such as Sir William Cubitt, a figurehead of British civil engineering, Bazalgette sharpened his skills and deepened his understanding of large-scale infrastructural projects.

His early career was a whirlwind tour of some of the most significant railway projects of the era. His notable contributions include his work on the London to Brighton Railway, a project that exemplified the rapid expansion and modernization of transportation during the Industrial Revolution. His experiences on this and other projects provided him with invaluable insights into the challenges and complexities of large-scale engineering ventures.

However, Bazalgette’s true calling came in 1849, when he transitioned to a new role in the Metropolitan Commission of Sewers. This marked a pivotal shift in his career trajectory, steering him away from the railways and towards the subterranean world of London’s sanitation system. Little did he know then, that this new path would lead him to conceive and implement one of the most transformative public health interventions in history.

The Sanitation Crisis in Victorian London

During the mid-19th century, the bustling metropolis of London was facing a grim and odorous reality. Rapid urbanization, fueled by the Industrial Revolution, had drawn a burgeoning population into the city. This population explosion led to severe overcrowding, as homes were tightly packed into narrow streets and alleyways, with minimal regard for sanitation or living standards.

The existing infrastructure was woefully inadequate to manage the city’s waste. Primitive waste disposal practices, such as cesspits and rudimentary sewerage systems, were overwhelmed. To compound the problem, many of these early sewers were designed to empty into the River Thames, the city’s primary water source. This led to the grotesque spectacle of the mighty Thames morphing into a fetid open sewer, its waters polluted with a grim cocktail of human and industrial waste.

In the sweltering summer of 1858, the sanitation crisis reached a tipping point in an event indelibly marked in history as the Great Stink. A prolonged heatwave led to a rise in the river’s temperature, exacerbating the already unbearable stench emanating from the sewage-laden Thames. The miasma was so overpowering that it permeated all corners of the city, rendering parts of it virtually uninhabitable. The stink even seeped into the hallowed halls of the Houses of Parliament, forcing a temporary suspension of governmental proceedings—a tangible sign of the urgency of the crisis.

However, the sanitation crisis was not merely a matter of discomfort or inconvenience. It was a severe public health disaster. The contaminated waters of the Thames became a breeding ground for waterborne diseases, most notably cholera. This virulent disease, which thrives in unsanitary conditions, led to recurrent outbreaks in the city, claiming thousands of lives. In the absence of a proper understanding of germ theory, these outbreaks were frequently attributed to miasma or bad air, further underscoring the urgent need for sanitation reform.

In this landscape of urban squalor and public health calamity, the stage was set for a revolution in urban planning and sanitation—a revolution that would be led by the visionary engineer, Sir Joseph Bazalgette. His pioneering work would not only resolve the immediate crisis but also lay the foundation for modern urban sanitation systems, transforming London and influencing cities around the world.

Bazalgette’s Innovative Vision

As the 19th century progressed, London found itself in the throes of a severe sanitation crisis. The rapid urbanization spurred by the Industrial Revolution resulted in a significant population boom, and the city’s existing infrastructure proved wholly inadequate to manage the mounting waste. This dire situation had far-reaching consequences on public health, environmental conditions, and the quality of life of London’s residents.

One of the most striking manifestations of this crisis was the state of the River Thames. As London’s population swelled and housing became more cramped, sewage disposal became a major issue. The prevailing practice was to dump waste directly into the river, which not only led to appalling levels of pollution but also transformed the Thames into a veritable open sewer.

The sanitation crisis reached a tipping point during the sweltering summer of 1858, an infamous period that came to be known as the Great Stink. Record-breaking temperatures intensified the already nauseating stench emanating from the contaminated Thames. The odour grew so unbearable that it permeated the streets and buildings, even forcing the temporary closure of the Houses of Parliament.

However, the ramifications of the sanitation crisis went far beyond the malodorous conditions. The polluted river presented a grave public health hazard. Contaminated drinking water, drawn from the Thames, led to recurring outbreaks of cholera—a deadly waterborne disease that claimed thousands of lives during the 19th century. The city also grappled with other illnesses linked to poor sanitation, such as typhoid fever and dysentery.

Victorian London’s public health crisis revealed the urgent need for a comprehensive solution. The existing infrastructure was clearly insufficient, and the city’s decision-makers were compelled to act. It was within this context that the visionary engineer Joseph Bazalgette entered the scene, devising a groundbreaking plan that would revolutionize London’s sanitation system and lay the groundwork for modern urban planning.

Through the concerted efforts of engineers like Bazalgette and the city’s officials, London managed to emerge from the depths of its sanitation crisis. The construction of a vast sewer network not only alleviated the immediate issues plaguing the city but also provided the essential infrastructure for future growth and development. As a testament to the enduring impact of these efforts, many aspects of Bazalgette’s original design remain in use today, serving as a reminder of the challenges that once faced Victorian London and the innovative solutions that transformed it.

The Construction of London’s Modern Sewer System

The construction of London’s modern sewer system, masterminded by Bazalgette, spanned a full decade, marking an unprecedented era of civil engineering. From 1860 to 1870, Bazalgette directed an extraordinary engineering endeavour that would forever alter the city’s landscape and its approach to public health.

This project was a monumental feat of engineering, demanding the deployment of both innovative techniques and extensive manpower. Bazalgette assembled a vast workforce that laboured tirelessly to transform his ambitious vision into reality. Despite the daunting scale and inherent complexity of the endeavour, Bazalgette’s indefatigable leadership and meticulous planning ensured that the majority of the project was effectively completed by 1870.

Bazalgette’s design for the sewer system was vast and intricate, comparable to a massive underground web spread beneath the bustling city. It comprised more than 1,100 miles of smaller, local sewers, designed to collect waste from individual streets and transport it into the larger network. These street sewers fed into 82 miles of main interconnecting sewers, larger conduits that served as the backbone of the system.

These main sewers, in turn, transported the accumulated waste to outfall sewers located on the eastern fringes of the city. Here, the waste was carried far downstream of the city, effectively eliminating the previous practice of discharging sewage directly into the Thames within populated areas.

The Thames Embankment was another significant facet of Bazalgette’s grand project. This ambitious undertaking involved the reclamation of large swathes of land from the river. Besides providing a new thoroughfare and public promenade, the embankment was ingeniously designed to house one of the main sewers, simultaneously hiding the city’s waste while showcasing the city’s progress.

Integral to the effective functioning of this elaborate network were two major pumping stations, Crossness and Abbey Mills. These were designed to lift the sewage from the lower-lying sections of London to the level of the outfall sewers, ensuring the smooth flow of waste through the system. Both stations were triumphs of Victorian engineering, embodying the fusion of functionality and aesthetic appeal.

Crossness and Abbey Mills, embellished with ornate ironwork and intricate architectural details, were more akin to cathedrals of industry than utilitarian sewage stations. Their architectural grandeur continues to draw admiration to this day, serving as enduring monuments to Bazalgette’s visionary approach and the transformative era of Victorian engineering.

The Impact of Bazalgette’s Sanitation System

The advent of Bazalgette’s comprehensive sewer system signified a groundbreaking moment in public health and urban infrastructure. As the new system took effect, the impact on public health was both immediate and profoundly transformative. Cholera, a virulent and frequently fatal disease that had once proliferated in the unsanitary conditions of the city, saw its relentless grip on London’s population drastically weakened. The disease outbreaks, which were once a devastatingly common occurrence, became a rarity, virtually disappearing from the city.

In addition to cholera, other diseases associated with inadequate sanitation, such as typhoid and dysentery, also witnessed significant reductions. The improvement in public health was not limited to the eradication of these diseases. The overall living conditions improved, leading to a healthier population, decreased mortality rates, and an increase in life expectancy.

Bazalgette’s ingenious sewer system didn’t just revolutionize public health; it also catalyzed London’s metamorphosis into a modern city, capable of sustained growth and development. The intricate network of sewers made it possible for vast swathes of the city to become habitable, providing the necessary infrastructure for London to expand beyond its existing boundaries.

Furthermore, by effectively diverting the city’s waste away from the River Thames, the sewer system played a pivotal role in reducing pollution in the waterway. This transformation had far-reaching effects, allowing the Thames to reclaim its place as the city’s lifeblood. The river, once a malodorous and toxic open sewer, experienced a rejuvenation, emerging as a bustling artery of commerce and transport. The cleaner Thames not only improved the quality of life for London’s residents but also attracted businesses, facilitated trade, and contributed to London’s rise as a global city.

The remarkable achievements of Bazalgette did not go unnoticed or unappreciated. In recognition of his significant services to public health and his role in transforming the city, Queen Victoria knighted him in 1874. However, his influence extends far beyond the accolades he received. Bazalgette left an indelible mark on the fields of civil engineering and urban planning. His work set new standards and introduced innovative principles that continue to guide how cities manage their infrastructure. His legacy is embodied in every modern city that prioritizes public health and sanitation, and in every engineer who strives to create solutions that benefit society at large.

Bazalgette’s Legacy Today

Today, more than a century and a half after its inception, London’s sewer system remarkably still functions largely on the principles and infrastructure instituted by Joseph Bazalgette. Testament to his prescient planning, Bazalgette designed the system to accommodate a population far exceeding the city’s size during the mid-19th century. His foresight ensured that as London burgeoned into the sprawling metropolis we know today, the foundational sanitation system was robust enough to meet the city’s evolving needs, albeit with necessary expansions and modernizations to keep pace with technological advancements and environmental considerations.

Bazalgette’s influence, however, extends far beyond the city limits of London. His revolutionary work in the realm of urban sanitation and public health policy has had a global impact, informing and influencing the development of urban infrastructures around the world. Cities across continents have emulated and adapted Bazalgette’s pioneering sewage system model, recognizing its efficacy in mitigating public health crises and facilitating sustainable urban growth.

Moreover, his profound understanding of the link between sanitation and public health has shaped modern public health policy. Bazalgette placed a strong emphasis on preventative measures in public health infrastructure—an approach that, in today’s world, is considered a fundamental principle in public health management. His vision underscores the importance of investing in comprehensive and well-planned infrastructure as a means of preventing, rather than reacting to, public health crises.

In the contemporary era, recognitions of Bazalgette’s far-reaching contributions have been numerous and varied. On the 200th anniversary of his birth in 2019, tech giant Google honoured Bazalgette with a commemorative Doodle, recognizing his transformative impact on London and, by extension, on urban living worldwide.

In his home city, tributes to Bazalgette are woven into the urban fabric. A blue plaque adorns his former residence in London, offering a tangible link to the man behind the city’s revolutionary sanitation system. There is a monument to Bazalgette situated on the Victoria Embankment, one of the significant public works projects that he oversaw. Perhaps most prominent is Crossness Pumping Station which serves as a constant reminder of Bazalgette’s indelible contributions, standing as a testament to a man whose vision and engineering prowess continue to underpin the functioning of one of the world’s most vibrant cities.

Episode 110: Crossness Pumping Station

Read more about Victorian London